|

Miracle Mile, Los Angeles

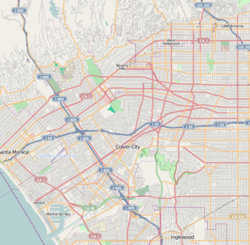

Miracle Mile is a neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles, California. [1] It contains a stretch of Wilshire Boulevard known as Museum Row. It also contains two Historic Preservation Overlay Zones: the Miracle Mile HPOZ[2] and the Miracle Mile North HPOZ.[3] GeographyMiracle Mile's boundaries are roughly 3rd Street on the north, Highland Avenue on the east, San Vicente Boulevard on the south, and Fairfax Avenue on the west. Major thoroughfares include Wilshire and Olympic boulevards, La Brea and Fairfax avenues, and 6th Street. [4] Google Maps identifies an irregularly shaped area labeled "Miracle Mile" that runs from Ogden Drive on the west to Citrus Avenue and La Brea Avenue on the east. The area is roughly bordered on the north by 4th Street and on the south by 12th Street.[5] History In the early 1920s, Wilshire Boulevard west of Western Avenue was an unpaved farm road, extending through dairy farms and bean fields. Developer A. W. Ross saw potential for the area and developed Wilshire as a commercial district to rival downtown Los Angeles. The "Miracle Mile" nickname first appeared in local newspapers on January 27, 1929.[6] The Miracle Mile development was initially anchored by the May Company Department Store with its landmark 1939 Streamline Moderne building on the west[7] and the E. Clem Wilson Building on the east, then Los Angeles's tallest commercial building. The Wilson Building had a dirigible mast on top and was home to a number of businesses and professionals relocating from downtown. The success of the new alternative commercial and shopping district negatively affected downtown real estate values, and triggered development of the multiple downtowns that characterize contemporary Los Angeles. Ross's insight was that the form and scale of his Wilshire strip should attract and serve automobile traffic rather than pedestrian shoppers.[6] He applied this design both to the street itself and to the buildings lining it. Ross gave Wilshire various "firsts," including dedicated left-turn lanes and timed traffic lights, the first in the United States. He also required merchants to provide automobile parking lots, all to aid traffic flow. Major retailers such as Desmond's,[6] Silverwoods, May Co., Coulter's, Harris and Frank, Ohrbach's, Mullen & Bluett, Phelps-Terkel, Myer Siegel, and Seibu eventually spread down Wilshire Boulevard from Fairfax to La Brea. Ross ordered that all building facades along Wilshire be engineered so as to be best seen through a windshield. This meant larger, bolder, simpler signage and longer buildings in a larger scale. They also had to be oriented toward the boulevard and architectural ornamentation and massing must be perceptible at 30 MPH (50 km/h) instead of at walking speed. These building forms were driven by practical requirements but contributed to the stylistic language of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne.  Ross's moves were unprecedented, a huge commercial success, and proved historically influential. Ross had invented the car-oriented urban form — what Reyner Banham called "the linear downtown" model later adopted across the United States. The moves also contributed to Los Angeles's reputation as a city dominated by the car. A sculptural bust of Ross stands at 5800 Wilshire, with the inscription, "A. W. Ross, founder and developer of the Miracle Mile. Vision to see, wisdom to know, courage to do." As wealth and newcomers poured into the fast-growing city, Ross's parcel became one of Los Angeles's most desirable areas. Acclaimed as "America's Champs-Élysées,"[8] this stretch of Wilshire near the La Brea Tar Pits was named "Miracle Mile" for its improbable rise to prominence. Although the preponderance of shopping malls and the development in the 1960s of financial and business districts in downtown and Century City lessened the Miracle Mile's importance as a retail and business center, the area has regained its vitality thanks to the addition of several museums and commercial high-rises.[6] The black and gold Deco Building in Art Deco style at 5209 Wilshire was built in 1929, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was designed by the architecture firm of Morgan, Walls & Clements, which also designed the Wiltern Theatre, the El Capitan Theatre, and other notable buildings in Los Angeles.[9][a] Wilshire Boulevard through Miracle Mile (Los Angeles) BuildingsLandmark buildings past and present, as well as some of the well-known businesses lining Wilshire during its main period as a retail center of Los Angeles (1930s–1960s). Architects: MWC = Morgan, Walls, & Clements, WB = Welton Becket & Associates Styles: AD = Art Deco, Ch = Churrigueresque, ︎SCR = Spanish Colonial Revival, SM = Streamline Moderne Italics indicate demolished buildings.

Museum Row   The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), The Petersen Automotive Museum, Craft Contemporary, George C. Page Museum, and La Brea Tar Pits pavilions, among others, create "Museum Row" on the Miracle Mile. The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, designed by Renzo Piano, is located in the former May Company Department Store on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue. A new contemporary structure for the museum's theaters is located behind the building.[21]  Historic Preservation Overlay ZonesMiracle Mile contains two Historic Preservation Overlay Zones. The Miracle Mile HPOZ comprises 1,347 properties. Its boundaries are Wilshire Boulevard to the north, San Vicente Boulevard to the south, La Brea Avenue to the east, and Orange Grove Avenue to the west. It is located in the city's Wilshire community plan area.[2] The Miracle Mile North HPOZ primarily consists of single-family residences which are uniform in scale, massing and setbacks, the majority of which were built from 1924 to 1941. Its boundaries are Gardner and Detroit streets, between Beverly Boulevard and Third Street. It is located in the city's Wilshire community plan area.[3] TransportationLos Angeles Metro's D Line subway is being extended along Wilshire Boulevard to the Veterans Affairs Hospital, from its current terminus at Western Avenue in Koreatown. In 1985, A federal ban on tunneling operations in the area was passed at the behest of the district's congressional representative Henry Waxman after an explosion, caused by the buildup of methane seeping up through the district's long-depleted oil wells, destroyed a department store. The ban was implemented despite the fact that methane deposits abound in most of Los Angeles. In late 2005, the ban was overturned, owing to tunneling techniques that make it possible to mitigate the methane concern. A westerly extension of the subway was then supported by many civic officials in Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, and Santa Monica,[22][23] the three cities through which the proposed extension runs. In early 2008, the project—which is destined to terminate in Santa Monica—received $5 billion in federal funds. In late 2008, Measure R passed, releasing $10 billion in reserve funds to start work on public transit projects in Los Angeles County. Service to three new stations, La Brea Station, Fairfax Station and La Cienega Station, is expected to begin in 2025.[24]  EducationThe area is within the Los Angeles Unified School District, Board District 4.[25] LandmarksLandmarks include The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Petersen Automotive Museum, SAG-AFTRA, the El Rey Theatre, La Brea Tar Pits, Park La Brea Apartments, 5900 Wilshire, Ace Gallery, the Zachary All building (5467), the Olympia Medical Center, and the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Johnie's Coffee Shop is leased mostly for filmmaking, but was also utilized as the west coast campaign office for Bernie Sanders presidential campaign, 2016. At the border on the Northwest corner is the Writers Guild of America, West, and at the border on the North is the Farmers Market, and The Grove, followed by Pan-Pacific Park. See also

References

Notes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Miracle Mile, Los Angeles.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||