|

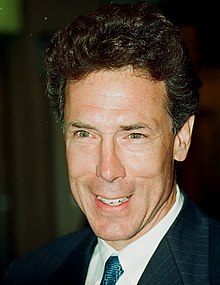

Mike Moore (American politician)

Michael Cameron Moore (born April 3, 1952) is an American attorney and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the Attorney General of Mississippi from 1988 to 2004. Early life and educationMichael Cameron Moore was born on April 3, 1952, in Jackson, Mississippi.[1] He grew up in Pascagoula in Mississippi's Gulf Coast region[2] and graduated from the city's Our Lady of Victory High School.[3] He attended Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College for two years before studying political science at the University of Mississippi, receiving a bachelor's degree from the latter in 1974.[4] He then received a J.D. from the University of Mississippi School of Law in 1976.[5][6] He married Letitia Rebecca Wood and had a son with her.[4] Early political careerIn 1977, Moore became an assistant district attorney in Mississippi's 19th Judicial District, representing Jackson, Greene, and George counties.[3][7] In 1979, he won election to the office of district attorney for the 19th Judicial District. Aged 26, he came into office in 1980 as the youngest elected official in Mississippi.[3] In his first year as district attorney, Moore prosecuted four of the five sitting Jackson County supervisors on corruption charges[8] stemming from the excessive purchase of seashells by the county to pave private driveways,[9] gaining statewide media attention.[10] During his tenure he also established youth education programs concerning child abuse and alcohol and illegal drug use.[11] He won reelection in 1983 with 83 percent of the vote[9] and left office in 1988.[3] Attorney General of MississippiElectionIn 1987, Moore ran for the office of Attorney General of Mississippi. In race which drew significant public attention, he defeated former Jackson mayor Dale Danks in the Democratic primary and won the general election.[12] He was the first Gulf Coast candidate to win a state office in over 100 years.[2] During the same election, Ray Mabus was elected governor and Dick Molpus was reelected secretary of state. The three of them were relatively young Democrats and shared similar goals in-so-far as ameliorating Mississippi's national reputation, supporting greater public health resources, and improving public education. The media collectively referred to them as the "boys of summer" and "the three musketeers".[13] Moore was sworn-in as attorney general on January 7, 1988.[14] Anti-corruption effortsIn May 1988, Moore successfully lobbied the Mississippi Legislature to pass a bill to allow the attorney general to investigate public corruption and convene grand juries and subpoena documents in such cases without a preliminary request from a local district attorney.[15] He established a white collar crimes unit in his office.[4] In 1992, he secured the indictment of Public Service Commissioner Sidney Barnett for taking illegal campaign contributions. Moore then negotiated Barnett's resignation and secured his cooperation into an investigation into other illegal contributions from utility companies to public service commissioners.[16] From 1995 to 1997, the office led a corruption investigation into local government in Clairborne County, culminating in the conviction of two county supervisors and another county employee for cashing fraudulent checks in early 1998.[17] Later in his tenure, he and State Auditor Phil Bryant established a good working relationship between their offices, such that the attorney general's prosecutors were able to quickly follow up on instances of fraud and embezzlement uncovered by auditors.[18] Asbestos litigationIn the 1980s, research increasingly affirmed that asbestos fibers, commonly used in building construction, caused various illnesses in people who inhaled it. Beginning in 1982, lawyers in Mississippi began filing tort cases against asbestos manufacturers and construction companies in pursuit of damages against adversely-impacted individuals.[19] On April 26, 1989, Moore filed a lawsuit in a circuit court on behalf of the state seeking $200 million in compensatory damages against 27 companies for the presence of asbestos in 221 state facilities, stating that the money could be used to renovate the buildings and remove the material. He hired attorney Richard Scruggs—a former law school classmate who had worked on several asbestos cases—on a 25 percent contingency to serve as the state's lead counsel.[20] Scruggs eventually won a settlement and earned $6 million from the state in legal fees. State Auditor Steve Patterson felt the arrangement was unethical, as Moore had no specific legal authority to contract out the work of his office to private attorneys and Scruggs had donated $20,000 to his 1991 campaign fund. In 1992 the auditor began working with the Hinds County district attorney to build a criminal case against Moore and Scruggs. Presley Blake, a political consultant, interceded and arranged for Patterson and Scruggs to meet, which resulted in Patterson dropping the inquiry and Scruggs reducing his fee for the state.[21] At Scruggs' urging, in 1994, state legislation was amended explicitly authorizing the attorney general to contract attorneys on contingency.[19][22] 1989 congressional candidacyIn August 1989, Representative Larkin I. Smith died in plane crash. A special election was scheduled for October to fill Smith's seat in Mississippi's 5th congressional district.[23] After consulting friends and family, Moore declared his candidacy for the seat on August 27, calling his decision "the toughest thing I've ever done in my life" but saying he felt the state required "the strongest voice we could get in Washington."[4] Democrat Gene Taylor and Republican Tom Anderson also entered the race.[23] During the brief campaign, Moore split his time between the events in the 5th congressional district and his work at the attorney general's office in Jackson.[4] He placed third and was eliminated in the first election.[23] Drug controlIn 1991, Moore began pushing for Mississippi to convene a statewide grand jury to consider indictments in drug cases across Mississippi,[24] arguing that a centralized jury could have access to more investigative resources than local ones. He convinced the Mississippi House of Representatives to pass a bill authorizing the creation of such a jury, but the proposal died in a Senate committee.[25] The effort succeeded in December 1993, when a judge ordered counties to offer names of registered voters to build a jury pool.[24] In 1992, President George H. W. Bush appointed Moore to the President's Commission on Model State Drug Laws, a body designed to study illegal drug-related issues and draft drug control legislation.[26] The body, of which Moore eventually became chairman, released its recommendations the following year, including 44 proposed laws.[27] Tobacco industry lawsuitIn the summer of 1993 attorney Mike Lewis approached law school classmate Moore with the suggestion of plaintiffs seeking damages against cigarette manufacturers to cover the medical costs of smoking-related illnesses, which were often incurred by the government. Moore was interested in the idea and directed Lewis to convey his proposition to Scruggs. As Scruggs began forming a team of attorneys in private practice to discuss the idea, Moore's office drafted plans for a lawsuit.[28][29] He eventually hired Scruggs' team, dubbed Health Care Advocates Legal Team.[30] In the spring of 1994 he and Scruggs turned over stolen tobacco company research documents to a United States congressional subcommittee evidencing tobacco companies' acknowledgment that they were selling addictive nicotine products.[31][32] On May 23, 1994, Moore filed a lawsuit on behalf of the state of Mississippi in the Jackson County Chancery Court against 13 tobacco manufacturing companies in pursuit of damages to cover the medical costs incurred by the state to treat persons afflicted by smoking-related illnesses.[33][34] He justified his the suit to the media by arguing, "This is a taxpayers' lawsuit. The bottom line is the [taxpayers] are paying hundreds of millions of dollars a year to treat people who have tobacco related disease."[33]  The chancery court judge allowed for a trial to proceed in February 1995.[35] Meanwhile, Scruggs secured the testimony of Merrell Williams Jr., a tobacco industry whistleblower, while Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice—who had expressed this disagreement with the tobacco lawsuit from the start, filed a lawsuit against Moore, hoping the State Supreme Court would block the attorney general's action. Fordice argued that Moore's proceedings were a publicity stunt and would damage efforts to attract industry to Mississippi.[36] Moore countered by deriding the governor as "a new Marlboro Man".[37] By the end of 1996, 19 other states had joined the lawsuit against the tobacco companies. In March 1997, the State Supreme Court ruled that it lacked jurisdiction to try Fordice's case against Moore and allowed the latter's suit to proceed.[38] The civil trial against the tobacco companies was scheduled for July 1997. Increasingly worried that they might lose the case, the companies sent representatives to negotiate a settlement with Moore and the 39 other state attorneys general who had joined the lawsuit. Moore demanded that he meet with the chief executive officers of the companies personally, and the companies acceded to his demands.[38] After a series of consultations in Washington, D.C., between the tobacco executives, Moore, and the other attorneys general, the Mississippi attorney general announced a settlement was reached in a press conference on June 20, with the tobacco companies agreeing to pay $368.5 billion to the 40 states involved, submit to new regulations, and significantly curtail their advertising.[39] The national settlement required the approval of the U.S. Congress, and though Moore, Scruggs, and others spent a year lobbying for the body to codify the agreement, their assent was never given and the deal was not carried out. In the mean time, Moore and other state attorneys general reached settlements for cases in their own respective states.[40] On July 3, 1997, Moore announced that the tobacco companies had agreed to give Mississippi $3.4 billion. The agreement also entailed a "most favored nation" rule which required the companies to offer Mississippi other favorable conditions negotiated in separate states. Thus, after Florida secured the companies' promise to remove billboard advertising in sports stadiums, similar signage was taken down in Mississippi.[40] The settlement was finalized by a judge in December.[41] At Moore's urging, in 1999, the legislature set aside the state's settlement money to form a healthcare trust fund.[10] Over the course of the 2000s the state legislature took money from the fund to cover other budgetary concerns before eventually abolishing the project. Reflecting on the outcome in 2022, Moore expressed disappointment that the trust fund had not lasted long but pointed to declines in tobacco use as worthy of celebration.[42] Moore received national attention for his role in the tobacco lawsuit.[12][43] In 1997 the National Law Journal named him its Lawyer of the Year[44][45] and the American Medical Association granted him a Dr. Nathan Davis Award for promoting public health.[24] In 1998, Governing included him in its Public Officials of the Year honors.[3][46] The 1999 Michael Mann-directed film The Insider portrays some of the events leading up to this settlement; Moore played himself in the film.[3][5] Pointing to his casting in the film, opponents accused Moore of using the tobacco issue to grandstand.[47] Civil rights and Mississippi burning caseIn February 1989, Moore settled a lawsuit against the state over the drawing of judicial districts in a manner which allegedly diluted the political strength of black voters. Citing their high cost to the state and the high probability of losing,[48] he announced that his office would no longer defend the state against civil rights lawsuits in court.[49] That year, two special assistant attorneys general in Moore's office recommended that the state of Mississippi reopen a criminal investigation into the 1964 Mississippi Burning murders of civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, citing the existence of "vital evidence" which made prosecution possible.[50] Moore declined to retry the case, and again rebuffed an appeal to retry it from one of the victim's brothers in 1997.[50] In 1998, The Clarion-Ledger published the transcript of a 1980s interview with Samuel Bowers, an erstwhile leader of the Ku Klux Klan who was convicted for his involvement in the murder of civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer. In the interview Bowers stated that he was glad Edgar Ray Killen—a suspect of the Mississippi Burning case—avoided prosecution.[51] Encouraged by the incriminating content of the interview and of the state's recent success in re-prosecuting other old civil rights murder cases, on February 25, 1999, Moore reopened the state's investigation into the Mississippi Burning murders.[52] Later that year, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation turned over thousands of documents related to their original inquiry of the case to the attorney general's office.[53] Moore and his investigators secured the cooperation of Cecil Price, a former deputy sheriff in Neshoba County who was privy to the details of the murders.[54] In 2000, the attorney general told journalist Jerry Mitchell of his disappointment that the state had never prosecuted the murders and said, "It is our belief at this point that Preacher Killen was one of the masterminds of the Neshoba County killings. We're making progress in the case. All the troops are excited."[55] Price died in an accident in 2001, which, according to Moore, "took a lot of wind out of our sails".[56] In November 2002, Moore told the press that while his office had the desire to re-prosecute the murders, it was struggling to build a strong criminal case.[57] By the end of the year the attorney general's office had suspended efforts to retry the case.[58] DepartureIn February 2003 Moore announced that he would not seek reelection to his office or campaign for any other position, surprising his own staff and many state politicians.[1][59] He declared his intention to enter private legal practice but left open the possibility of running for other offices such as governor or a U.S. Senate seat in the future.[10] Moore was succeeded by Jim Hood as attorney general on January 8, 2004.[60][61] Moore served as an early adviser for his successor.[19] Hood and local prosecutors ultimately reopened the investigation into the Mississippi Burning case.[62] Private practice After leaving office, Moore entered private legal practice and created Mike Moore Law Firm LLC, based in Flowood, Mississippi. The firm specialized in corporate-government relations. In 2003, Moore began representing clients who sued Purdue Pharma, claiming the company had gotten them or family members addicted to prescription opioid painkillers. The cases were settled in 2007, but as a result of the effort Moore became familiar with opioid-related litigation and formed relationships with other attorneys with experience in the subject. With the opioid epidemic in the United States continuing and prescriptions for opioids increasing, several state government considered pursuing legal action against pharmaceutical companies. In 2014 Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine contracted a group of lawyers led by Moore to build a case against several drug suppliers. In May 2017 they filed a lawsuit against Purdue Pharma, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Janssen, Endo, and Allergan, accusing them of concealing the addictiveness of opioids and violating Ohio laws concerning fair business practices.[5] In 2018, Moore was hired by the government of Hillsborough County, Florida, to lead its lawsuit against 14 companies for alleged violations of state law with regards to the aggressive marketing of opioid drugs. The companies agreed to settle with the county in 2021.[63] References

Works cited

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||