|

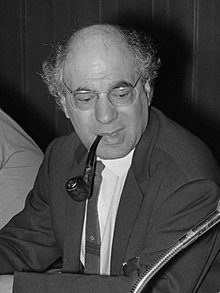

Maxime Rodinson

Maxime Rodinson (French pronunciation: [ʁɔdɛ̃sɔ̃]; 26 January 1915 – 23 May 2004) was a French historian and sociologist. Ideologically a Marxist, Rodinson was a prominent authority in oriental studies. He was the son of a Russian-Polish clothing trader and his wife, who both were murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp. After studying oriental languages, he became a professor of Ge'ez at the École pratique des hautes études. He was the author of a body of work, including the book Muhammad, a biography of the prophet of Islam. Rodinson joined the French Communist Party in 1937 for "moral reasons"[citation needed] but was expelled in 1958 after criticizing it. He became well known in France when he expressed sharp criticism of Israel, particularly opposing the settlement policies of the Jewish state. Some credit him with coining the term Islamic fascism (le fascisme islamique) in 1979, which he used to describe the Iranian Revolution. BiographyFamilyThe parents of Maxime Rodinson were Russian-Polish Jewish immigrants who were members of the Communist Party.[1][2] They arrived in France at the end of the 19th century as refugees from pogroms in the Russian Empire. His father was a clothing trader who set up a business making waterproof clothing in the Yiddish-speaking part of Paris, called the Pletzl, in the district of the Marais. They became port-of-call for other Russian exiles, most of them revolutionaries hostile to the Tsarist regime. His father tried to unionise and organize educational and other services for his working-class immigrant group. In 1892, he helped to establish a community library, containing hundreds of works in Yiddish, Russian, and French. In 1920, the Rodinsons joined the Communist Party and as soon as France recognized the Russian SFSR, in 1924, they applied for Soviet citizenship. Rodinson grew up in a fervently Communist, non-religious and anti-Zionist family.[3] Early life and educationRodinson was born in Paris on 26 January 1915. Neither he nor his sister learned Yiddish. The family was poor, so Rodinson became an errand boy at the age of 13 after obtaining a primary school certificate. But his learning thrived through borrowed books and obliging teachers who didn't demand payment,[3] and Rodinson began to study oriental languages, at first on Saturday afternoons and in the evenings. In 1932, thanks to a rule allowing persons without academic qualifications to take the competitive entrance examination, Rodinson gained entry to the Ecole des Langues Orientales and prepared for a career as a diplomat-interpreter. He studied Arabic but later, preparing a thesis in comparative Semitics, he also learned Hebrew, which surprised his family. In 1937, he entered the National Council of Research, became a full-time student of Islam, and joined the Communist Party.[3] Syria and Lebanon (1940–1947)In 1940, after the beginning of the Second World War, Rodinson was appointed to the French Institute in Damascus. His subsequent stay in Lebanon and Syria allowed him to escape the persecution of Jews in occupied France and extend his knowledge of Islam. His parents were murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. Rodinson spent most of the next seven years in Lebanon, six as a civil servant in Beirut and six months teaching in Sidon at the Maqasid[dubious – discuss] high school.[4] Professor of Oriental Languages and Marxist without a partyIn 1948, Rodinson became a librarian at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, where he was put in charge of the Muslim section. In 1955, he was appointed director of studies at the École pratique des hautes études, becoming a professor of classical Ethiopian four years later. Rodinson left the Communist Party in 1958, following Nikita Khrushchev's revelations of Stalin's crimes[4] amid accusations of using the association to further his career, but nonetheless remained a Marxist. According to Rodinson himself, the decision was based on his agnosticism, and he explained that being a party member was like following a religion and he wanted to renounce "the narrow subordination of efforts at lucidity to the exigencies of mobilization, even for just causes." He became well known when he published Muhammad in 1961, a biography of the prophet's life written from a sociological point of view, a book which is still banned in parts of the Arab world. Five years later, he published Islam and Capitalism, a study of the economic decline of Muslim societies. He participated with other colleagues committed to the left (Elena Cassin, Maurice Godelier, André-Georges Haudricourt, Charles Malamoud, Jean-Paul Brisson, Jean Yoyotte, Jean Bottero) in a Marxist think tank organised by Jean-Pierre Vernant. This group took on an institutional form with the creation, in 1964, of the Centre des recherches comparées sur les sociétés anciennes, which later became the Centre Louis Gernet, focusing more on the study of ancient Greece.[5] He was awarded the 1995 Prize by the Rationalist Organisation.[dubious – discuss] Rodinson died on 23 May 2004 in Marseille. Israeli–Palestinian conflictSupport for Palestinian self-determinationRodinson took a public stance in favour of Palestinian self-determination during the Six-Day War. A few months before publishing his famous article, Rodinson took part in a meeting organized in the "Mutualité" in Paris for the Palestinian struggle. Published in June 1967 under the title "Israel, fait colonial" (Israel, a colonial fact) in Jean-Paul Sartre's journal, Les Temps Modernes, Rodinson's article made him known as an advocate of the Palestinian cause. He created the Groupe de Recherches et d'Actions pour la Palestine with his colleague Jacques Berque. At that time, he observed that the Palestinian struggle was a cause embraced mainly by the antisemitic right and Maoist fringe of the left. He called on the Palestinians to take their case to liberal Europeans, warning them of the danger of a religious nature of the conflict which would tarnish the reputation of a just cause:

Theoretical stanceHis anti-Zionism was based on two main reproaches: pretending to impose on all people of Judaic descent all over the world an identity and a nationalist ideology, and judaizing territories at the cost of expulsion and domination of the Palestinians. Hence, in his book Israël and the Arabs in 1968, he considered the Palestinians as the single national fact in the Palestinian territories:

Elsewhere, he emphasized that

His approach to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict included a call for peaceful negotiations between Israeli Jews and Palestinians. Israel could not be regarded only as a colonial-settler state but a national fact too. Israeli Jews had collective rights that the Palestinians had to honour:

That is the reason why he disagreed with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), warning them against the illusion based on the Algerian FLN guerilla warfare which had driven out French "colons". At the same time, he urged the Israelis to stop pretending to be part of Europe and accept being a part of the Middle East, then, Israelis have to learn to live with their neighbours, by reckoning the injustices made against the Palestinians and adopting a language of conciliation and compromise. Studying Islam from a Marxist and sociological point of viewRodinson's work combined sociological and Marxist theories, which, he said, helped him to understand "that the world of Islam was subject to the same laws and tendencies as the rest of the human race." Hence, his first book was a study of Muhammad (Muhammad, 1960), setting the Prophet in his social context. This attempt was a rationalist study which tried to explain the economical and social origins of Islam. A later work was Islam and Capitalism (1966), the title echoing to Max Weber's famous thesis regarding the development of capitalism in Europe and the rise of Protestantism. Rodinson tried to rise above two prejudices: the first one widespread in Europe that Islam is a brake for the development of capitalism, and the second one, widespread among Muslims, that Islam was egalitarian. He emphasized social elements, seeing Islam as a neutral factor. Throughout all of his later works on Islam, Rodinson stressed the relation between the doctrines inspired by Muhammad and the economic and social structures of the Muslim world. Rodinson also coined the term theologocentrism for the tendency to explain all empirical phenomena in the Muslim world with reference to Islam, while ignoring the role of "historical and social conditioning" in explaining events.[7][8][9][10] In his book Mohammed (1971), Rodinson writes:

Works by Maxime RodinsonThis list refers to the English editions.

See alsoNotesReferences

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Maxime Rodinson.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||