|

Mastanabal

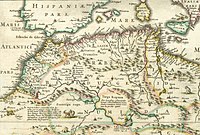

Mastanabal (Numidian: MSTNB; Punic: 𐤌𐤎𐤕𐤍𐤏𐤁𐤀, MSTNʿBʾ)[1][2] was one of three legitimate sons of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in, present day Algeria, North Africa. The three brothers were appointed by Scipio Aemilianus Africanus to rule Numidia after Masinissa's death.[3] His name in Numidian was written as "MSTNB" which Salem Chaker gave its possible reconstruction as "Amastan (a)B(a)", which could mean "defender/protector (a)b(a)".[4] BiographyWell versed in Greek literature,[5] he learned law. Mastanbal is a great sportsman and Athlete since his youth, the prince took part in chariot races and the Panathenaic Games. He was a sportsman who was passionate about horseback riding. He owned a stud farm of purebred horses. Around 168 BC or 164 BC, he won a gold medal at the Athens Hippodrome at the Panathenaic Games in the prestigious horse-drawn chariot racing event.[6] According to the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus, after the death of his father in 148 BC, Mastanabal was given authority over the administration of Numidia. The Greek historian of the Roman period Appian states in his work "Roman History", that Mastanabal shared power with his brothers Micipsa and Gulussa, receiving the charge of judicial affairs.[7] While his elder brother Gulussa left with a cavalry division to join the Roman forces fighting Carthage during the Third Punic War, Mastanabal remained in Numidia with his brother Micipsa. His death must have taken place before that of Micipsa, that is, in 140 B.C. The historian Sallust states in his work "War of Jugurtha", that Mastanabal succumbed to an illness. Jugurtha, one of his sons, was later adopted by his uncle Micipsa. He thus became the king's co-heir with the king's own legitimate children, Adherbal and Hiempsal, whom he later put to death in a coup d'état in order for Jugurtha to remain sole sovereign.[8] His other son, Gauda (from a second marriage), was made subsidiary heir. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||