|

Marchantia polymorpha

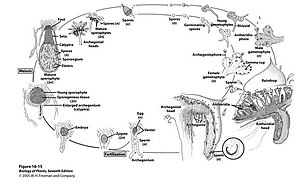

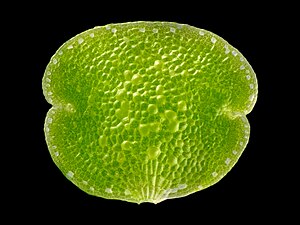

Marchantia polymorpha is a species of large thalloid liverwort in the class Marchantiopsida.[1] M. polymorpha is highly variable in appearance and contains several subspecies.[2] This species is dioicous, having separate male and female plants.[2] M. polymorpha has a wide distribution and is found worldwide.[3] Common names include common liverwort or umbrella liverwort.[2] DistributionMarchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis has a circumpolar boreo-arctic cosmopolitan distribution, found worldwide on all continents except Antarctica.[4] HabitatMarchantia polymorpha grows on shaded moist soil and rocks in damp habitats such as the banks of streams and pools, bogs, fens and dune slacks.[1] While most varieties grow on moist substrates, Marchantia polymorpha var. aquatica is semi-aquatic and is often found invading marshes, as well as small ponds that do not have a consistent water table.[3] The species often grows in man-made habitats such as gardens, paths and greenhouses and can be a horticultural weed. One method of spread is in the production and sale of liners. Liners infested with M. polymorpha, often in association with silvery thread moss, are commonly grown in one region of the country, transported to another region to continue growth, and are shipped to a retail location before being planted. Plants have the potential to pick up or disperse these species at each point of transfer.[5] Marchantia polymorpha is known to be able to use artificial light to grow in places which are otherwise devoid of natural light. A study from Niagara Cave showed that under such conditions, Marchantia polymorpha was able to produce gemmae, indicating that the plant could be able to reproduce in illuminated caves.[6] It has also been reported from Crystal Cave in Wisconsin.[7] EcologyAn important benefit of M. polymorpha is that it is frequently the first vegetation to appear after a large wildfire. Exposed mineral soil and high lime concentrations present after a severe fire provide favorable conditions for gametophyte establishment. After invading the burned area, M. polymorpha grows rapidly, sometimes covering the entire site. This is important to the prevention of soil erosion that frequently occurs after severe fires, causing significant, long-term, environmental damage. In addition, M. polymorpha renews the humus in the burned soil, and over time raises the quality of the soil to a point where other vegetation can be established.[3] Not only does common liverwort secure burned soil and improve its quality, but after a certain point, when the soil health is restored, it can no longer compete with the vegetation that originally inhabited the area. In a USDA study in northeastern Minnesota, M. polymorpha dominated the landscape for 3 years after a severe fire, but after 5 years was replaced by lichen. After a similar fire in New Jersey M. polymorpha covered the ground for 2–3 years, but was then replaced with local shrubs and forbs. In Alaska the following vegetative successions were observed after a fire, again indicating that after soil rehabilitation has occurred the original flora returns and outcompetes M. polymorpha.[3] Morphology It is a thallose liverwort which forms a rosette of flattened thalli with forked branches. The thalli grow up to 10cm long with a width of up to 2cm. It is usually green in colour but older plants can become brown or purplish. The upper surface has a pattern of polygonal markings. The underside is covered by many root-like rhizoids which attach the plant to the soil.[2] The complex oil bodies in Marchantia polymorpha, as in all Marchantiopsida species, are restricted to specialized cells where they occupy nearly the entire intracellular space.[8] Life cycle and reproduction Life cycleThe life cycle has an alternation of generations. Haploid gametophytes produces haploid gametes, egg and sperm, which then fuse to form a diploid zygote. The zygote later develops into a sporophyte which later produces haploid spores through meiosis. Reproduction Sexual reproductionThe plants produce umbrella-like reproductive structures known as gametangiophores. The gametangiophores of female plants (also known as archegoniophores) consist of a stalk with star-like rays at the top. These contain archegonia, the organs which produce the ova. Male gametangiophores (also known as antheridiophores) are topped by a flattened disc containing the antheridia which produce sperm.[2][9] Asexual reproductionThis species reproduces asexually by gemmae that are produced within gemma cups. Gemmae are lentil shaped and are released by droplets of water. Plants produced in this way can expand a patch significantly.[2]  Bioindicator for pollutionThe U.S. Department of Agriculture has studied M. polymorpha for its use in rehabilitating disturbed sites due to its ability to tolerate high lead concentrations in soils, along with other heavy metals. In turn, M. polymorpha colonies can be an indication that a site has high concentrations of heavy metals, especially when found in dense mats with little other vegetative species present.[3] A study from Loja city in tropical Ecuador found that, when growing in an urban setting, M. polymorpha bioaccumulated four heavy metals, aluminium, copper, iron and zinc.[10] Human useIt has historically been thought to remedy liver ailments because of its perceived similarities to the shape and texture of animal livers.[11] This is an example of the doctrine of signatures. Marchantia polymorpha produces the antifungal bis[bibenzyls] dihydrostilbenoids plagiochin E, 13,13'-O-isoproylidenericcardin D, riccardin H, marchantin E, neomarchantin A, marchantin A and marchantin B. Its strong fungicidal capability has been used successfully in the treatment of skin and nail fungi.[12] See alsoGallery

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||