|

Mannerism in Brazil

The introduction of Mannerism in Brazil represented the beginning of the country's European-descended artistic history. Discovered by the Portuguese in 1500, Brazil was until then inhabited by indigenous peoples, whose culture had rich immemorial traditions, but was in every way different from the Portuguese culture. With the arrival of the colonizers, the first elements of a large-scale domination that continues to this day were introduced. During the founding of a new American civilization, the main cultural current in force in Europe was Mannerism, a complex and often contradictory synthesis of classical elements derived from the Italian Renaissance - now questioned and transformed by the collapse of the unified, optimistic, idealistic, anthropocentric world view crystallized in the High Renaissance - and of regional traditions cultivated in various parts of Europe, including Portugal, which still had in the earlier Gothic style a strong reference base. Over the years the current was added of new elements, coming from a context deeply disturbed by the Reformation, against which the Catholic Church organized, in the second half of the sixteenth century, an aggressive disciplinary and proselytizing program, the so-called Counter-Reformation, revolutionizing the arts and culture of the time. Due to the fact that the establishment of Portuguese civilization in Brazil started from scratch, there were scarce conditions for a cultural flourishing for almost a whole century. Therefore, when the first important artistic testimonies began to appear in Brazil, almost exclusively in the field of sacred architecture and its internal decoration, Mannerism was already in decline in Europe, and was succeeded by the Baroque in the first half of the 17th century. However, mainly due to the activity of the Jesuits, who were the most active and enterprising missionaries, and who adopted Mannerism almost as an official style of the Order, resisting much in abandoning it, this aesthetic was able to expand abundantly in Brazil, influencing other orders. Nevertheless, the style they cultivated most in the colony was the Portuguese Plain Style architecture (Estilo Chão in Portuguese), with austere and regular features, strongly based on the classicist ideals of balance, rationality, and formal economy, contrasting with other trends in Europe, which were much more irregular, anti-classical, experimental, ornamental, and dynamic. The basic model of the facade and in particular the floor plan of the Jesuit church was the most enduring and influential pattern in the history of Brazilian sacred edification, being adopted on a vast scale and with few modifications until the 19th century. The Portuguese Plain Style architecture also had a profound impact on civil and military construction, creating an architecture of great homogeneity spread throughout the country. As for the internal decorations, including gilded wood carving, painting and sculpture, Mannerism had a much shorter lifespan, disappearing almost completely from the mid 17th century, with the same occurring in the literary and musical fields. Despite its strong presence, most of the Mannerist churches were decharacterized in later reforms, and today a relatively small number of examples survive in which the most typical traces of the Early Architecture are still visible. Their internal decorations, as well as the examples in music, suffered an even more dramatic fate, being lost almost in entirely. Critical attention to Mannerism is a recent phenomenon; until the 1940s, the style in general was not even recognized as an autonomous entity in History of Art, considered until then a sad degeneration of Renaissance purity or a mere stage of confused transition between the Renaissance and the Baroque, But since the 1950s a great number of studies have begun to focus on it, better delimiting its specificities and recognizing its value as a style rich in proposals and innovative solutions, and interesting in its own right. About the Brazilian case, however, the difficulties are much greater, research is in its initial phase and the bibliography is poor, there are still many mistakes, anachronisms and divergences in its analysis, but some scholars have already left important contributions for its recovery. Mannerism  Mannerism emerged in Italy as a natural evolution of the Renaissance, which had flourished between the 14th and 15th centuries, spreading a return to the classicist aesthetic ideals of formal balance, economy of means, and moderation in expressiveness, ideals that were associated with the highest moral values. The Renaissance reached its full objectives in the so-called High Renaissance phase (c. 1480–1527), usually delimited by Leonardo da Vinci's mature work and the Sack of Rome in 1527, producing an art of great dignity, stability, and solemnity, which had in a nature purged of its transitory imperfections, in the primacy of reason over subjectivity, and in the production of the consecrated masters of the past its ideal foundations. However, the imitation of nature was loaded with formalism and idealism, it proposed the presentation of a utopian world, where Good reigns on Earth under the benevolent power of Heaven, and differences are annulled under a great homogenization of culture and way of life, where people follow a pure and altruistic ethic. In fact, one of the Renaissance artists' concerns was to offer educational models of conduct, which could transform society and give it lasting happiness. If this ideology was the mainstay of the great art produced in this period, it was at the same time artificial, divorced from everyday reality, being cultivated in a period of almost incessant wars and major socio-political crises. In this context, two crises were especially dramatic: the bloody Sack of Rome in 1527, one of the culminating points of a complete reorganization in European geopolitics, which definitively struck down Italy's political and economic primacy on the European scene, and the Reformation begun in 1517, which split the once monolithic Christianity into two different sects, which until then had been the most important factor in preserving Europe's cultural and religious unity, and which had given Italy singular international political influence as the head of Christianity.[2][3][4][5] Then, Mannerism is, first of all, the fruit of these profound changes in Italian society, and if before the classical values of the High Renaissance could still preserve a façade of cultural unity and of an optimistic and peaceful world, in a short time even art was no longer able to sustain it, appearing works that were ambiguous, agitated, questioning, not infrequently cynical, hedonistic, irrational, hermetic, precious and frivolous, and even bizarre, obscure, fantastic and grotesque. Therefore, Mannerism confronted Classicism advocated and that had proven to be an ideal too high to be materialized, presenting the world as a place of conflicts, contradictions, uncertainties, insufficiencies, and dramas, where violence, falsehood, and cruelty were habitual political methods, religious dogmatism subjugated consciences and wills, hunger, wars, and epidemics were constant threats, and simple survival was for the vast majority of people a poignant and pressing challenge.[6][7][8] It was not by chance that Giulio Argan defined Mannerism as "the triumph of practice over theory".[9] But there were other factors. The Renaissance had its own contradictions, and while on the one hand it preached respect for the production of the great masters of the past as models of perfection to be imitated, on the other it had long been proposing that artists deserved to be equated with intellectuals, with the result that in the High Renaissance artistic individualities were significantly strengthened and the figure of the genius emerged, a creator who more than gaining independence from the rules, in fact established new rules and became in turn a new model. This cultivation of individualism and freedom of thought and creation, combined with a period of great general insecurity and the collapse of previously solidly established and very homogeneous standards, contributed to make Mannerist art highly personalist, much freer from the bonds of the ancient canons, making room for a pulverization of the general style in a multitude of personal, local and regional derivations, which were close to or far from Classicism in very different degrees.[10][7][6][11] In a second stage, the Catholic reaction to the Reformation, the so-called Counter-Reformation, which wanted to moralize and discipline customs and the clergy, reaffirm the dogma and regain the lost faithful, changed the context.[12] Throughout the evolution of Mannerism, the classical reference, in fact, was not eliminated from art, but rather it was tested, discussed, relativized, disarticulated, transformed, and even combated, but it remained the basis on which later advances emerged, adapting it to a new social, political, and cultural universe.[13][14] In Vítor Serrão's summary,

On the international scene, however, the emergence of Mannerism occurred in a different context. The crises mentioned were not exclusively Italian, and classical values were also cultivated in other countries, in good measure through Italian influence, but its flowering never became as dominant as in Italy, where it totally obliterated the traces of the Gothic style, which preceded the Renaissance, and which in Italy came to be considered an aberration produced by barbarian peoples. Throughout the wide region north of the Alps and in Western Europe, Gothic traditions were still thriving vigorously in the 15th century, and it was mainly from their fusion with classical elements that the so-called International Mannerism was born, an extremely polymorphous aesthetic current, considering the large number of regional traditions in existence and the varied ways in which they blended with classicist influences.[15][16][17] The phenomenon of Portuguese Mannerism, the direct origin of Brazilian Mannerism, was inserted in this context. The Portuguese version  Portugal remained for a long time immersed in the Gothic, especially of Flemish origin, and belatedly received the classical influence, which only began to be noticed with more vigor in the early 16th century, exactly when it began to decline in its place of origin. The Portuguese contact with the classical world was, therefore, mainly through the Mannerist filter. At the end of the reign of Manuel I of Portugal, contact with Italy intensified, either directly or through Spain, and an Italianized style began to appear that reflected more, among all the Mannerist strands, the Roman fashion. Among its most important precursors was Francisco de Holanda, who studied in Rome and when he returned to his country was a great disseminator of the new aesthetic through his work as an architect, decorator, painter, and treatise writer. Several other Portuguese artists received royal scholarships to study in Italy, and some notable Italian architects settled in Portugal. At the same time, important treatises on architecture began to circulate, such as Medidas del Romano, by the Spaniard Diego de Sagredo, and De Architettura, by the Italian Sebastiano Serlio, along with the introduction of a large number of Italian engravings, which exerted a decisive influence, along with the royal scholarship painters, on the renewal of painting, causing the new current to begin a great flowering in all artistic modalities. Minor Moorish, French, and Germanic influences added even more variety to the scene.[18][19][1] In the words of Vítor Serrão

In BrazilWhile Portugal continued with its millenary artistic tradition, transplanting its culture to the newly discovered Brazil meant creating a new civilization in a territory until then dominated by indigenous peoples, whose culture radically diverged from the Portuguese, developing a model of society that was divided between itinerant hunter-gatherer groups and other semi-sedentary groups that had agriculture as an important subsistence base. They also maintained millenary artistic traditions, but their architecture was limited to simple straw-covered dwellings, the ocas, sculpture was almost unknown and painting had a figurative tradition that was only schematic, focusing on traditional geometric or abstract patterns that suffered little modification over centuries, with a strong folkloric and ritual character.[21][22][23][24][25] Lacking a previous structure, it is natural that the first hundred years of Portuguese colonization were characterized by difficulties and shortages of all kinds, with the struggle for survival in an inhospitable environment concentrating interests and efforts. Therefore, what emerged in terms of art and architecture in this period was generally shabby and bare. However, as the defense of the territory against hostile indigenous peoples, adventurers and pirates from other nations was a major concern, several fortifications were erected along the coast, some of them quite large. At the same time, as the spiritual needs of the new settlers had to be met, the Catholic Church participated in the settlement process by sending many missionaries, among them Jesuits, Dominicans, Carmelites, Benedictines and Franciscans, who in general had a solid cultural background, many of them also being talented artists, the founders of Brazilian art with European descent. The missionaries, together with military engineers, whose activities involved much more than just building fortifications and barracks, were responsible for the projects of the first churches, chapels, schools and hospitals, and also participated in their erection. The religious were also responsible for the first Brazilian expressions of painting, sculpture, literature and music in European molds. However, the indigenous peoples made some contribution in the form of some decorative and constructive techniques.[26][27] On the other hand, the missionaries were not all Portuguese, many came from Italy, Spain, France or Germany, and brought varied aesthetic references. The heterogeneity of the influences received, along with the difficulties of communication with the mainland, created a gap in relation to the aesthetic chronology of Europe, and caused the evolution of Brazilian art to be marked by large doses of eclecticism and that archaisms persisted for a long time. At the same time, these factors often make it difficult to identify exactly the predominant trend in each individual work, producing endless controversies among critics.[9][27] Architecture   Churches: Phase OneDue to the sacred character of the vast majority of the most important buildings erected in the colony, the influence of the aesthetics cultivated by the different religious orders was decisive in shaping Brazilian architectural Mannerism, with the Jesuits and, to a lesser degree, the Franciscans as its most active representatives. The first important nucleus of activity was the Northeast, with the cities of Olinda, Recife and Salvador standing out. A little later, centers were formed in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The Jesuits formed an Order typified by their great general culture and by the pragmatism and adaptability of its members to the local contexts. Their buildings adopted as basic model the Portuguese Mannerist style known as Portuguese Plain Style architecture (Estilo Chão in Portuguese), characterized by functionality and adaptability to multiple uses, ease of construction, and relatively low costs, and could be used in the most varied contexts. The great versatility and practical viability of the Plain Style served the interests of both the Church and the Portuguese State, at a time when both were closely united through the patronage system, with the religious being important agents in the organization and education of society and also in the process of building the overseas empire.[26] Another style, the Manueline, also known as Portuguese late Gothic, much more complex and refined, with a strong emphasis on the Gothic heritage and incorporating Moorish influences, did not have important repercussions outside continental Portugal. The most ornate and dynamic version of Italo-Portuguese Mannerism, which left important monuments in Portugal, such as the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora and the Church of Our Lady of Grace in Évora, and in the colonies in the Orient, where the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Old Goa (Goa Velha in Portuguese) and the Church of Mother-of-God in Macau, among others, stand out for their ornamental richness, did not prosper in Brazil, with rare exception. The Se Cathedral, also in Old Goa, on the other hand, is very similar in its austerity and balance to the floor standards adopted in Brazil.[1] The basic floor plan of the Portuguese Plain Style was defined by a single rectangular nave, without transept and dome, and with a chancel at the back, where the main altar was located, bordered by a large cross arch, at the ends of which two secondary altars could be installed, or none at all. Especially important buildings could have three naves or other secondary altars installed in niches along the single nave. On these altars, especially, the decorative richness that the conditions of each site could allow was applied.[26][1] According to Gustavo Schnoor, it is possible that this model was inspired by Portuguese Gothic churches with a single nave.[28] The facades were as a rule extremely simple, derived from the classical temple model, with a square or rectangle as the main body, pierced by a row of straight lintel windows on the upper level, and crowned by a triangular pediment. The surface of the facades was little three-dimensional and had a stripped ornamentation, occasionally adorning the pediments with volutes and pinnacles, and the portals with columns and discreet reliefs on the frontispiece, emphasizing the sobriety, balance, and order appreciated by the classicists. The belfries, one or two, were implanted in the plane of the façade, following the austerity of the rest of the building, and covered by pyramid-shaped or ribbed dome corbels, but sometimes they were reduced to towers integrated to the main body or placed apart from the church. This church model would be the most influential and lasting contribution of Mannerism to Brazilian art, being adopted on a large scale until the 19th century.[1][26] In 1577 the Jesuits sent Father Francisco Dias, a renowned architect, to Brazil, with the purpose of giving Brazilian temples the dignity they still lacked. He was a follower of Vignola and Giacomo della Porta, famous Italians whose style had fallen in the favor of the court and who participated in the construction of the Church of the Gesù in Rome, which became a model for a myriad of other Jesuit temples around the world. Soon after, another Italian, Filippo Terzi, built the important Church of São Vicente de Fora and finished the first Jesuit church in Portugal, the Church of Saint Roch, in Lisbon, whose master builder was the same Francisco Dias. Dias would leave works in various parts of Brazil, among them the reform of the Church of Our Lady of Grace, in Olinda.[26][1] According to Gabriel Frade,

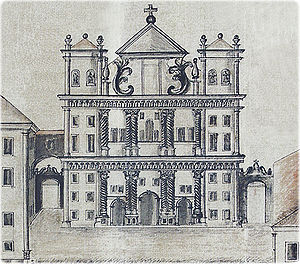

For John Bury, the Jesuits were exposed to two main influences, the tradition inaugurated by the Church of the Gesù in Rome, the matrix of all the Jesuit churches in the world, and the tradition of São Vicente de Fora, the matrix of the Portuguese churches, and the Brazilian buildings would reveal either a predominance of one or the other, or they would make original syntheses of both, exhibiting quite different styles: the first derived from the model of the rectangle topped by a triangular pediment, and without towers, and the other with a rectangular block flanked by two towers, and without a pediment.[1]  Meanwhile, the Franciscans also engaged in intense building activity, and like the Jesuits, had a leading exponent in the Friar Francisco dos Santos. Their only surviving works are the Convent of Saint Francis in Olinda, partially destroyed by the Dutch and whose church was restored in a Baroque style, and the Convent of Saint Anthony in Rio de Janeiro, also with a later modified church. His other works have been lost entirely, but reports of the time state that he and his collaborators owned an original style. These novelties are probably reflected in other Franciscan churches of the period, expressed in a lower pediment, the presence of a porch or a galilee in front of the entrance, more ornamental and dynamic facades, the belfry set back from the facade, a narrower nave often flanked by ambulatories with side altars installed in niches, and a sacristy placed at the back of the church, usually occupying the entire width of the building. They were also distinguished from the Jesuits by their love of decorative luxury and the greater variety of architectural solutions, and by the greater speed with which they adopted decorative formulas typical of the Baroque. Other important 16th century Franciscan buildings are the convents and churches of Igarassu and João Pessoa.[26] The Church of Saints Cosme and Damião, in Igarassu, started in 1535, is the oldest church in Brazil that still preserves its original recognizable features, although the tower is partly baroque. Other good examples of the first construction phase are the Church of Our Lady of Grace, built in Olinda between 1584 and 1592 on a chapel of 1551, and the Olinda Cathedral, erected between 1584 and 1599, which after much modification was returned to a conformation very close to the primitive one in the 1970s.[29] Churches: Phase Two  A second stage developed from the middle of the 17th century, after the initial difficulties were overcome, when the territory already had a significant life of its own, was becoming richer and began to develop an autochthonous culture differentiated from the metropolis, with many artisans and native artists already active. However, the Government of Portugal still had as its primary interest the economic exploitation of the colony, and invested little in improvements, in social assistance, in art and in education, continuing to place on the Church the main responsibilities of instructing the people, providing medical care, supporting the orphans, the widows and the elderly, registering the born and burying the dead, continuing to virtually dominate much of Brazilian life and, moreover, still being, as it had been from the beginning, the great cultural patron, since the massive majority of artistic projects, large or small, remained in the sacred field. In this phase, the distinctions between the Jesuit and Franciscan styles, and those of the other orders, become more difficult to determine, and there is a great overlapping of tendencies.[9][1] John Bury highlights two churches as the most representative of this second phase: the Cathedral Basilica of Salvador and the Church and College of Saint Alexander in Belém. The present Cathedral is the fourth to be erected on the same site, being completed in 1672. Formerly the church of the Jesuit college, after the demolition of the Old Cathedral of Salvador it had the status of a Cathedral. "An exceptionally vast and imposing building, which undoubtedly exerted considerable influence on churches built later, not only by the Jesuits, in Bahia and other parts of the colony. Its facade is very severe, with small towers integrated into the main body. The interior is also austere in its basic conception, with a single nave, a chancel flanked by two subsidiary chapels, and others arranged along the nave. On the other hand, the decoration of the altars is luxurious and refined, some of them still preserving Mannerist traits, and others in Baroque style. The Church of Saint Alexander, inaugurated in 1719, is more archaic and has affinities with the Portuguese Plain Style, despite its voluptuous pediment. The interior is similar to the example in Salvador, although less sumptuous. Bury describes it saying that "the more crude techniques and the unfamiliarity with classical rules in a way freed the project from the restrictions manifested in Salvador. [...] The overall effect is not sophisticated, but original and robust, that is, colonial in the best sense of the term".[1] Other important buildings also deserve mentioning. The mentioned Old Cathedral of Salvador, according to the drawing made by Luís dos Santos Vilhena in 1802 (illustrated in the opening of this article), was a vigorous and monumental example of a more ornamental Mannerism, despite the regularity of the division of its surface and its openings. It took on its definitive configuration in the early 18th century, but in the 19th century it deeply deteriorated and was demolished in 1933.[30] The Mother of God Church in Vigia, Pará, was founded in 1734, and according to Renata Malcher de Araujo, "is one of the most interesting buildings of the Society [of Jesus] in Brazil, especially for its imposing upper side porches, ornamented by twelve thick Tuscan columns, which support the wooden roof of the temple," a unique case in Brazil. The pediment has affinity with the Church of Saint Alexander.[31][1] The mannerist profile still subsists in the current form of the imposing Cathedral of São Luís in Maranhão, with a compact volumetry derived from Portuguese Plain Style architecture, but the pediment was all modified and the surface of the facade received a new relief treatment in the 20th century, but its chancel still preserves a magnificent mannerist altarpiece. The Church and Convent of São Francisco in Salvador still has many mannerist elements in the general composition of the facade, but the ornamentation of the exterior and especially the interior is baroque.[28][1] Still to be mentioned are the Church of the Holy Cross of the Military in Rio de Janeiro, directly inspired by the Church of the Gesù in Rome,[27] the Main Church of Santo Amaro das Brotas, with an important carved portal,[32] the Church of the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy (Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Portuguese) and the Church of the Convent of Saint Teresa, both in Salvador,[28] the churches of the Benedictine monasteries in Salvador and Rio de Janeiro, with a structure aligned to the plain aesthetics and interiors decorated in the baroque style, possessing great historical and artistic value, the Church of Rosário dos Pretos in Fortaleza, and the Main Church in Maragogipe, also in the same line.[33][34][28]

Churches: Phase ThreeThe last phase of architectural Mannerism developed mainly in Minas Gerais in the first half of the 18th century, when the Brazilian Gold Rush occurred and the region became a major economic, political and cultural center. A more recent settlement area, its first built monuments still follow the model of the Early Modern Architecture in its austerity and adherence to straight lines, although the interiors are already baroque decorated. The Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Assumption in Mariana and the Main Church of Sabará are good representatives.[1]  Mannerist Architecture would still have a long survival in Brazil, although its influence went through a certain decline from the second half of the 18th century on, giving way to Baroque and Rococo.[35] Several important authors already recognize its extensive trajectory. For Sandra Alvim, "Mannerist architecture has great penetration, takes root, and becomes a formal prototype. In what concerns plans and façades, it guides the rigid character of the works until the 19th century",[36] Gustavo Schnoor says that "the long duration of Mannerism [...] would put it in contact, almost in continuity, with the advent of neoclassical taste, which turned to the models of its own classical tradition, that is, to Mannerism, before taking interest in Ancient Rome, Greece, or the Renaissance",[28] and in John Bury's view,

Other typologies Military buildings, where fortifications stand out, were another field in which the Baroque was largely ignored, predominating the principles of Portuguese Plain Style architecture of simplicity, ornamental dispossession, and adaptability. Their specific characteristics favored this, since when it came to such buildings the main concerns were about functionality and efficiency, without major aesthetic considerations.[37][27] Fortifications also went through a recognizable typological evolution. Between the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 16th century Portugal was building in the so-called "Transitional Style", adapting to the recent introduction of firearms, producing an architecture that blended elements from the old medieval castles and the first modern fortresses. According to Edison Cruxen, among the most modified elements in this transition were the old Gothic turrets, which reduced their height and lost their polygonal shape, becoming circular or semicircular, more resistant to artillery. They were called cubelos, defined as low towers, bulky and protruding from the wall, and constituting "the beginnings of the bastions that would gain definition and establish themselves in a period of full use of pyrobalistic artillery. The battlements are reinforced and the breastplate, an extra protection at the base of the wall in the forts located by the sea, is introduced. At the same time, the barrier, an evolution of the barbican, located at the base of the land walls, gains increasing importance and begins to receive openings for the installation of artillery pieces to defend against the low fire that destroyed the base of the walls.[38] However, these changes were not adopted in all forts at the same time, having a long period of experimentation and adaptation to the evolution of artillery, appearing a variety of constructive solutions.[39][38] Besides this, the first Brazilian defenses, due to the lack of materials and technical builders, were built in clay or in the form of wooden palisades, requiring frequent repairs, but soon the concern with solidity and resistance was imposed, being replaced by masonry.[37][38] The first important fort to be erected in the colony was Fort of São João, in Bertioga, built in 1553 on an old palisade, following a mannerist aesthetic.[38] In the words of J. Silva,

The period between the Iberian Union and the Portuguese Restoration War, in the 17th century, represents a new phase in military construction. There was a large-scale restructuring of the old fortifications, which became lower and more compact, to blend in better with the skyline and stop being easy targets, while some of the main features of the Transitional Style, such as the towers and battlements, disappeared.[27] Reflecting the changes in the military art, new treatises appeared, with Serrão Pimentel's Método Lusitano de Desenhar as Fortificações (1680) and Azevedo Fortes' O Engenheiro Português (1728) standing out.[40][37] At the same time, the Portuguese conquest was advancing through the interior of the continent over Spanish areas, and many other new fortifications were being built, especially on the land frontier to the west of the territory, in order to secure the conquest. The 18th century still witnessed significant activity, and most of the surviving examples date from this time.[38][27] In the 19th century fortifications found less and less use, few were erected, and if in 1829 there were almost 180 forts in operation, in 1837 there were only 57. Many were abandoned and degraded, and others were adapted for new uses.[37][40][41] Despite the prioritization of functionality in fortifications, military engineers were well prepared and often well informed about the art and erudite architecture of their time, as evidenced by their knowledge of the treatises of Vitruvius, Vignola and Spannocchi, among others, their frequent collaboration in religious constructions and the many projects they left for churches and chapels. In addition, many of the most important fortifications had some ornamental detail in their portals, barracks and chapels.[27][37] A few examples are enough to show the enormous importance of military engineers. The Church of the Holy Cross of the Military in Rio de Janeiro was the work of Brigadier José Custódio de Sá e Faria.[27] The Monastery of St. Benedict, in the same city, was designed by the illustrious Francisco Frias de Mesquita, chief engineer of Brazil, who designed the city floor plan of São Luís in Maranhão and was the author of some of the most important fortifications of the 17th century, such as Reis Magos Fort and Marcelo Fort.[42] In São Paulo, the military engineer João da Costa Ferreira was praised by Governor-General Bernardo José de Lorena, who mentioned that he was loved by the people due to his performance teaching everyone how to build well with local resources. Brigadier José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim is considered the diffuser of arched lintels on windows and doors in the mid-18th century with his project for the Palace of the Governors in Ouro Preto, which became an almost ubiquitous pattern in civil construction, strongly associated with the Baroque style.[27] In addition to the Governor's Palace, Alpoim designed the reform of the Carioca Aqueduct and the construction of the Convent of Saint Teresa, the Convent of Ajuda, the Palace of the Viceroy, the Church of Our Lady of the Conception and Good Death, the cloister of the Monastery of St. Benedict and several fortifications, designed the floor plan of the city of Mariana, was a professor in the course of artillery and fortifications and wrote two important treatises, the Exam of Artillerymen (Exame de Artilheiros in Portuguese) in 1744 and the Exam of Firemen (Exame de Bombeiros in Portuguese) in 1748.[43]   In fact, military engineers played a fundamental role in the Brazilian architectural evolution, not only in the military and religious fields, but also in the popular and civilian ones, designing, building, supervising works, organizing production systems, opening roads, planning cities, acting in politics and also teaching.[37][27] Carlos Alberto Cerqueira Lemos says:

Manor houses, colleges, and monasteries are other noteworthy typologies that were built with simple, regular lines and decorative austerity in the facades, with straight lintel windows and occasionally a discreetly ornamented portal, seeking functionality rather than luxury. The vast majority of the original buildings were knocked down or disfigured in later renovations.[1] Examples that are still more or less intact are the former Town House and Jail (Casa de Câmara e Cadeia in Portuguese) in Salvador, the Tower House of Garcia d'Ávila (Casa da Torre in Portuguese) in Mata de São João,[28] the Convent of Saint Anthony in Rio de Janeiro (its church is baroque),[44] the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy in Salvador, the former Jesuit school in Belém, the Solar de São Cristóvão on the outskirts of Salvador, the Palace of the Eleven Windows (Palacete das Onze Janelas in Portuguese) in Belém, and the Solar Ferrão in Salvador.[1] Among the manor houses, a separate category is formed by the so-called bandeirista architecture, generally farmhouses, developed most intensely in the old São Paulo Province and typified by a classic floor plan, where the centralized great hall of multiple use and the porch between two rooms of social function stand out, which in general served one as a chapel and the other as a guest room. Its roof was four-sloped and its lines very stripped. A very common typology in the 16th and 17th centuries, today only a few examples remain, among them the Butantã House (Casa do Butantã in Portuguese), the Tatuapé Farm House (Casa do Sítio Tatuapé in Portuguese), and the Regent Feijó House (Casa do Regente Feijó in Portuguese).[45] It was in architecture that Mannerism left its most vast, lasting and influential legacy in Brazil, and little remains of its expression in other artistic categories.

Music Practically nothing has been saved from the music practiced in the first two centuries of colonization, except literary references. Through them we know that music, especially vocal, was an integral part of religious worship and was cultivated with intensity. In the secular sphere it was also present at all times, both in public ceremonies and in the recesses of the home, but even less is known about this aspect than about sacred music. There seems to have been nothing comparable to the sophisticated and hermetic music of the Italian Mannerist courts, with its extravagant harmonies, irregular melodies, and broken rhythms. On the other hand, there are records citing the practice of polyphonic music in the major churches, which already maintained stable choirs and instrumental ensembles from the 17th century on. However, sacred music was closely tied to the conventions established by the Counter-Reformation, when it reverted in part to polyphonic practices in the so-called "Old Style" or Prima Prattica, but characterized by solemnity, simplicity of writing, and accessibility, avoiding the complex counterpoint techniques of the late Gothic and Renaissance that often obscured the texts in a mass of voices singing different words at the same time, as opposed to the "Modern Style" or Seconda Prattica that described more advanced music. Notwithstanding the canonical impediments, in Portugal an exuberant and artificial sacred style developed in parallel, which possibly had reflections in Brazilian practices as well.[46][47] The theorist Antônio Eximeno left an illustrative account:

Nery & Castro also refer that Mannerism lasted in Portuguese music long after the Baroque was already the dominant musical style in Italy, a process that took place between 1630 and 1640, with a main cultivation of the mass genres, of the motet and the vilancico in the sacred field, and of the tento and fantasy for the profane music, all inherited from the 16th century, while some of the fundamental genres of the Italian Baroque of the 16th century, such as opera, cantata, oratorio, sonata, and concerto, remained absent. A consistent update for the Baroque would only begin in Portugal during the reign of João V (r. 1706–1750). In Brazil, from the very little evidence available - a small handful of anonymous works, some other literary references and the treatise Organ Singing School (Escola de Canto de Órgão in Portuguese) (1759-1760) by Caetano de Melo de Jesus, which makes references to older practices - after timid beginnings in the early 18th century, the new style only seems to have taken hold after the 1760s, even then still cultivating archaisms and stylistic ambiguities. However, the Baroque presence seems to have been as brief as it was fragile, and by the end of the century a transition to Neoclassicism began, when Brazilian music began to be better documented and understood.[46] Sculpture and gilded wood carving In contrast to the austere facades of Portuguese Plain Style architecture, the interiors of the most important churches and convents could be decorated with great luxury, including statuary, paintings, and gilded wood carving. However, little remains of the early Mannerist decoration in these places, the vast majority of which has been distorted by later reforms or lost entirely. In sculpture, traces of a classicism almost only appear in the early production of sacred statuary, characterized by its solemnity and staticity, by faces with impassive expression, and by vestments that fall flat to the ground, which contrast with the bustling and dramatic patterns of the Baroque from the 17th century on. The surviving collection is small and almost always made of clay, and the pieces are small in size. Their characterization as part of Mannerism is controversial, and in general this production is analyzed as proto-Baroque. In any case, the images created by João Gonçalves Viana and by the religious Fray Domingos da Conceição da Silva, Fray Agostinho da Piedade and his disciple Fray Agostinho de Jesus, who were active between the 16th and 17th centuries, serve as examples.[48][28][49] Also included in the sculpture category are the architectural reliefs which still remain in portals of manors, churches and convents, of which the doorway of the Co-Cathedral of St. Peter of Clerics in Recife is a good illustration, but the most significant example is the Church of the Third Order of Saint Francis in Salvador, an absolutely unique case in Brazil for the extraordinary ornamental richness of its façade, showing affinities with the Plateresque style, a branch of Spanish Mannerism, and which some critics identify as a proto-Baroque. Its only stylistic similar, much less rich and exuberant, is the Church of Our Lady of Guia in Lucena, Paraíba.[50][51][1] The richness of the interiors was justified by canonical precedents that subverted the anti-reformist rules of austerity, such as the opinions of Charles Borromeo himself, one of the great articulators of the Counter-Reformation.[1] In John Bury's analysis,

However, unlike the Franciscans, who early on adopted the luxurious Baroque patterns, the Jesuits preserved in the gilded carving of the altars classicist archaisms and a sense of greater sobriety, with a low volumetric treatment, little dynamism in the forms, the use of isolated columns with straight shafts, abundance of geometric motifs, a high quality craftsmanship and a division of the areas based on rectangular planes. The altars have a great variety of structures, but a conformation that imitates church façades is not rare, with a base support, an intermediate level with columns and niches, and a pediment as crowning.[52][28][1] In the words of Lúcio Costa

The decorative style of carving has undergone a much faster evolution than the facades and floor plans, and by the mid 17th century Mannerism had almost entirely disappeared from colonial temples, replaced by the first phase of the Baroque, the so-called Portuguese National Style. There survive, however, a few examples that attest to the sophistication of Brazilian Mannerist carving. Among the main ones are three lateral altars in the Cathedral Basilica of Salvador, the main retable of the Cathedral of São Luís, three lateral altars in the Church of Our Lady of Good Success in Rio de Janeiro, which formerly belonged to the Jesuit college, the secondary altars of the Church of Our Lady of Grace, in Olinda, the oldest in Brazil, made in a much more stripped style,[53][1][28] the main retable of the Church of Our Lady of Comandaroba, in Laranjeiras, the main altar of the Church of the Magi in Nova Almeida, the altarpieces of the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary in Embu das Artes,[28] the main altar of the Church of Saint Lawrence of the Indians in Niterói, the main altar and two secondary altars with statuary of the Church of the Convent of Our Lady of the Conception in Itanhaém, and the altar of the Chapel of Voturuna in Parnaíba.[54] Also surviving are the altar of the second Main Church of São Vicente, an altarpiece from the Chapel of Engenho Piraí in Itu, important fragments of the altars from the Benedictine monastery of Santana de Parnaíba, and various decorative elements from the interior of the Old Cathedral of Salvador, preserved in the Museum of Sacred Art of the Federal University of Bahia, among which are capitals, colonnades, angels, caryatids, fragments of carved wood, a silver altar table, torches, furnishings, all, according to Rafael Schunk, in the Mannerist style.[55]

Painting and graphic artsOther categories in which scarce testimonies survives are painting and the graphic arts. Early travelers and explorers often relied on draughtsmen and engravers in their expeditions, charged with making a visual record of the fauna, flora, geography, and native peoples. Among them can be mentioned Jean Gardien, illustrator of the book Histoire d'un Voyage faict en la terre du Brésil, autrement dite Amerique, published in 1578 by Jean de Léry, Theodor de Bry, illustrator of the book Duas Viagens ao Brasil by Hans Staden, and Priest André Thevet, probable illustrator of his three scientific books published in 1557, 1575, and 1584. The prints of these artists show Mannerist traits in their representation of human bodies, with an anatomical description and a system of standard proportions, heirs of the idealistic naturalism of the Renaissance, but already impregnated with a more precious approach and a contorted dynamism inspired by Michelangelo, in compositions that often distort the central point perspective so dear to the Renaissance, creating a new spatiality, and eschewing the typically classical clarity and order.[56][57][58]   In painting, the first known record is by the Jesuit priest Manuel Sanches (or Manuel Alves), who was Salvador in 1560 on his way to the East Indies and left at least one painted panel in the Jesuit school. Shortly afterwards comes the Jesuit Belchior Paulo, who arrived in 1587 along with other priests and left decorative works scattered in many of the largest colleges of the Society of Jesus until the early seventeenth century, but only a few works attributed to him are known, among them an Adoration of the Magi, today in the Church of the Magi in Nova Almeida, Espírito Santo, which shows Flemish influence.[59][60][61] In a separate setting, a remarkable artistic flourishing occurred around the court of the Dutch invader Maurice of Nassau, established in Pernambuco between 1630 and 1654, gathering illustrators, painters, philosophers, geographers, humanists and other specialized intellectuals and technicians. In painting, the figures of Frans Post and Albert Eckhout stand out, leaving works of high quality and within a calm and organized classicist spirit that has little affinity with the more typical nervous and irregular pictorial Mannerism, and that until today are one of the most important primary sources for the study of landscape, nature and the life of indigenous peoples and slaves of that region. On the other hand, the allegorical and decorativist character of Eckhout's compositions and his tendency towards the artificial "whitening" of the blacks and the indigenous peoples, and the doses of fantasy and incongruities in the montage of scenes that could not have existed in reality in Post, both created images that had a cultural and political programmatic content recognized and made explicit at that very time, and were more the materialization of the desires and idealizations of the nobility and the illustrated bourgeoisie in Netherlands - who bought his works and mythified the tropical world - than scientific descriptions of the land, are elements that in some ways bring them closer to the mannerists. Most of this production returned to Europe, but a small part can still be found in Brazilian museums.[62][63][64][65] Also surviving in various churches and convents are some panels and ceilings of decorative painting, including some on tiles, which reveal a transition to the Baroque style, using plants in intricate interweaving, reminiscent of plateresque decoration, interspersed with religious symbols, images of saints and other figures, as exemplified by the important ceiling of the sacristy of the Church of Saint Alexander in Belém. Another great example, of a very pure Mannerism, is the sacristy ceiling of the Cathedral-Basilica of Salvador, derived from the Roman-inspired Grottesque style, with a series of medallions inserted in the wood carving, with floral frames and portraits of Jesuit saints and martyrs in the center.[66] Schnoor also identifies as Mannerist a large full body portrait of Gonçalo Gonçalves, the Young Man, and his wife Maria, in the gallery of benefactors of the Holy House of Mercy in Rio de Janeiro, the celebrated Christ of Martyrdoms by Friar Ricardo do Pilar, although others identify it as a Baroque work, and a painting depicting Saint Rita of Cascia in her church in Rio de Janeiro.[28] In the case of tile painting, it is almost invariably ornamental, without figurative scenes, or at most with tiny figures scattered among rich patterns of vegetal or geometric motifs, in the so-called "Carpet Style", accomplished with a color palette limited to a few shades. This tile was generally applied as a bar at the bottom of corridor walls and around the courtyards of conventual cloisters, in church interiors and more rarely in residences and public buildings.[28]

LiteratureThe context of the early colonial times conditioned and limited Brazilian literary production even more intensely than in other arts. There were no schools except for those run by priests and study was practically limited to basic literacy and religious catechesis, illiteracy was widespread, the press was forbidden for a long time, the circulation of books was very small and invariably passed through the sieve of government censorship, generally being chivalric romances, catechisms, almanacs and some dictionaries and treatises about law, legislation and Latin. There was no paper production, and even the Portuguese language did not establish itself on a large scale until the middle of the 18th century, being spoken mainly in hybrid languages of Portuguese and indigenous languages, factors that combined to make the local literary scene almost non-existent. After the great precursors active in the second half of the 16th century, the Jesuits José de Anchieta, author of historical chronicles, grammars, sacred acts and poetry, and Manuel da Nóbrega, author of Diálogo sobre a Conversão do Gentio and a rich epistolary collection, Only in the 17th century, other writers began to appear, among them Bento Teixeira, author of Prosopopeia, the first Brazilian epic poetry, the poet Manuel Botelho de Oliveira, the Jesuit António Vieira, publicist of sacred prose, and Gregório de Matos, great author of sacred, lyrical and satirical poetry. Although they dealt with local themes, all their work is still a direct extension of Portuguese literature.[67][68][69]  Except for Anchieta and Nóbrega, by the time the others flourished, the literary Baroque was already beginning to become the dominant style in Portugal. However, Mannerist traces are clearly perceptible in many moments, in particular due to the overwhelming influence of Camões in the metropolitan literary production, who shows his Mannerism through the intense atmosphere of political and spiritual crisis in his writings, in the absence of any certainty, in his famous feeling of disenchantment and melancholy towards the lost "classical paradise", in the opposition between the high ethics of Renaissance humanism and the perception of real man's inadequacies and wickedness, in the strangeness and desire to escape from the world, in the religious propaganda, in the use of complex figures of speech and artful gimmicks, and in the taste for contrast, emotional excitement, conflict, paradox, dreamlike and fantastic atmospheres, and even the grotesque and the monstrous.[70][71][72][67] According to Walkyria Mello, "the Mannerist poet became obsessed with the tragic feeling of life, with the misery of man, the heir to a legacy of pain [...]. Melancholy and anguish are also constant themes in Mannerist poetry, and it is because his worldview is somber and permeated with suffering."[73] These traits would be accentuated in the later Baroque production and would become its most distinctive features, found also in the production of the writers mentioned before, and that is why they are often understood primarily as Baroque and not Mannerist.[74] Nóbrega's work, of high literary value, was characterized more by its objective realism and the balance of his analyses of local reality,[75] but Anchieta is the most clearly mannerist of all in his eclecticism and his recurrent syncretism of classical, medieval and other elements derived from local reality, in the timelessness that permeates his dramatic situations, in the juxtaposition of characters from different traditions, in the use of indigenous languages alongside Portuguese.[76][77][78][79] For Eduardo Portella,

Several other writers worked between the 16th and 17th centuries occupied with historical or chorographical works, talking about the land and the indigenous customs, but their main interest lies in their documental character and not so much in their style, more objective and purely informative. Noteworthy are Gabriel Soares de Sousa with his Notícia do Brasil, Fernão Cardim, with his Narrativa Epistolar e os Tratados da Terra e da Gente do Brasil, Pero de Magalhães Gândavo, author of Tratado da Terra do Brasil and História da Província Santa Cruz, possibly the most literary of this set, steeped in the Camões tradition, purified however by a sense of sobriety and simplicity, and Vicente do Salvador, author of História do Brasil and Crônica da Custódia do Brasil.[81][82] Critical fortune The stylistic characterization of Mannerism is a recent phenomenon in Art History, which still arouses significant controversy. Although its main traits have been identified already by the Baroque, it was massively rejected as a phase of decadence and degeneration, where Renaissance purity and idealism would have been put down by skeptical and disturbed spirits, or seen only as an uncertain transitional period between the "great ages" of Renaissance and Baroque. This view held up until the first half of the 20th century.[83][84][53][36][35] Among the main scholars of the movement are Max Dvořák, who in the early twentieth century penetrated the Mannerist spiritualist, metaphysical, and religious dimension, making a valuable and pioneering contribution to its recovery;[85][53] Nikolaus Pevsner, who in the 1940s broadened its definition to include all aspects that arouse instability, discontinuity or conflict, consolidated the links between Mannerist painting and the architecture produced in the same period and contextualized the movement, explaining it as a reflection of the agitated social and religious panorama of that period, in an article that became influential;[86] and in the following decade, Arnold Hauser made a fundamental contribution by extensively studying Mannerism under its stylistic, political and social aspects, included literature, and introduced the concept that Mannerism promoted a move away from imitation of nature, being a conscious reaction against tradition and the precursor of modern art, further distinguishing among its more or less classicist currents, the origin of a polarity that created paradoxes and that for him was an essential feature of the movement.[87] Around the same time Eugenio Battisti and Hiram Haydn wrote influential and thoughtful works dealing with varied aspects and demanding a revision in historical categories,[53] Wolfgang Lotz studied its architecture and better defined its chronology,[86] and Walter Friedländer refined his periodization and refuted the idea that the movement was a decadence of the Renaissance.[88][53] More recently Georg Weise analyzed the influence of the Gothic and made one of the best distinctions between Mannerism and the Baroque,[89][53] Ernst Robert Curtius left perhaps the best study on the literature,[90] and Gustav René Hocke devoted himself to the philological aspects in an anti-historicist approach.[91] Since then, studies have multiplied rapidly and style has gained increasing recognition as an autonomous entity in historiography.[92][28][53]  When it comes to Brazilian Mannerism, the situation is more difficult. Some important pioneering authors like Germain Bazin used the concept in their works, but it was still poorly defined. They were more interested in the Baroque and still tended to understand Mannerism as a transitional stage. Roberth Chester Smith and John Bury, in several essays published between the 1940s and 1960s, on the other hand, already embraced it in its full legitimacy, applying it to describe with consistency and depth broad sectors of national art, focusing however on the study of architecture.[93][86] But Smith and Bury's advanced works have been little read in Brazil until recently,[93] and the old prejudices still exert considerable influence. Some authors still do not recognize its autonomy and describe it as a late Renaissance or as proto-Baroque, a certain current, in view of the strong classical descent of its architectural expression, removes the Portuguese Plain Style from the Mannerist sphere, others place under the broad and indistinct category of Colonial Architecture everything that was built between the 16th and the beginning of the 19th century, and its chronological delimitation is not consensual either.[28][33] Gustavo Schnoor talked about the polemic:

However, despite the disputes, the most recent international trend is to understand Mannerism as a movement independent of both the Renaissance, although derived from it, and the Baroque, which succeeded it and grew on its bases. But the theme has not yet received exclusive treatment by national critics, and its concepts are employed only occasionally in writings dealing with the Baroque, the theme of colonial art history that still monopolizes academic attention. An exception is Schnoor, author of the only study published so far that deals exclusively with the movement in its specifically Brazilian expression, O Maneirismo no Brasil (2003), although it is a short article. Rafael Schunk gave great attention to Brazilian Mannerism in its various artistic expressions in his master's dissertation Frei Agostinho de Jesus e as tradições da imaginária colonial brasileira - séculos XVI-XVII (2012).[94][33][28] A body of knowledge that recovers in depth and disseminates on a large scale the Mannerist legacy in Brazil has yet to be created. See alsoReferences

|