|

Malajoe Batawi

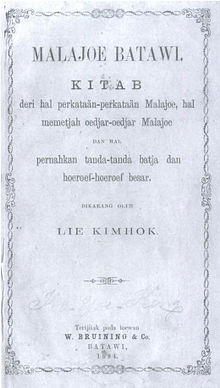

Malajoe Batawi: Kitab deri hal Perkataan-Perkataan Malajoe, Hal Memetjah Oedjar-Oedjar Malajoe dan Hal Pernahkan Tanda-Tanda Batja dan Hoeroef-Hoeroef Besar[a] (better known by the short title Malajoe Batawi; Perfected Spelling: Melayu Betawi; literally Betawi Malay) is a grammar of the Malay language as spoken in Batavia (now Jakarta) written by Lie Kim Hok. The 116-page book, first published in 1884, saw two printings and has been described as the "most remarkable achievement of Chinese Malay writing".[1] Background and writingDuring the late 1800s numerous books and newspapers had been published in Batavia (now Jakarta) using a creole form of Malay. These books, including translations of Chinese works, did not use a standardised language. Some were written entirely in one sentence, with a single capital letter at the beginning and a single full stop at the end.[2] Lie Kim Hok (1853–1912) was a journalist and teacher who wrote extensively in the creole. He considered the lack of standardisation appalling, and began to write a grammar of the language to ensure a degree of regularity in its use.[2] The same year he published Malajoe Batawi, he released Kitab Edja (Spelling Book), a book to teach spelling to schoolchildren.[3] ContentsMalajoe Batawi's 116 pages consist of 23 pages discussing the use of capital letters and punctuation, 23 pages discussing word classes, and the remainder regarding sentence structure and writing.[4] Lie discusses various morphemes, including the active-transitive morpheme [me(N)-] and the active-intransitive [ber-].[5] Lie identifies ten word classes in Malajoe Batawi, as follows:[5]

Release and receptionMalajoe Batawi was published in 1884 by W. Bruining & Co. in Batavia. Tio Ie Soei, in his biography of Lie, describes it as first grammar of Batavian Malay,[4] while linguist Waruno Mahdi calls it the first "elaborate grammar of a Malay dialect along modern lines".[1] The book saw an initial print run of 500 copies.[4] According to Tio, it came under consideration for use as teaching material in local schools. However, the publisher requested changes with which Lie disagreed, and ultimately the deal fell through.[2] A second edition was published by Albrecht & Rusche in 1891,[6] and towards his death in 1912 Lie began writing a new edition of Malajoe Batawi. However, he died before it could be completed.[4] In 1979, C.D. Grijns opined that, based on the primarily oral nature of Betawi, Lie did not base his Malajoe Batawi on spoken language, but the written language used by ethnic Chinese merchants.[7] Malaysian press historian Ahmat B. Adam describes Lie as leaving "an indelible mark on the development of modern Indonesian language",[8] while Mahdi writes that the grammar was the "most remarkable achievement of Chinese Malay writing" from a linguist's point of view.[1] Notes

FootnotesReferences

|

||||||||||||||||