|

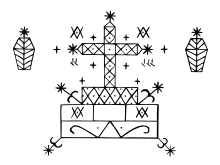

Lwa Lwa, also called loa, are spirits in the African diasporic religion of Haitian Vodou and Dominican Vudú. They have also been incorporated into some revivalist forms of Louisiana Voodoo.[a] Many of the lwa derive their identities in part from deities venerated in the traditional religions of West Africa, especially those of the Fon and Yoruba. In Haitian Vodou, the lwa serve as intermediaries between humanity and Bondye, a transcendent creator divinity. Vodouists believe that over a thousand lwa exist, the names of at least 232 of which are recorded. Each lwa has its own personality and is associated with specific colors and objects. Many of them are equated with specific Roman Catholic saints on the basis of similar characteristics or shared symbols. The lwa are divided into different groups, known as nanchon (nations), the most notable of which are the Petwo and the Rada. According to Vodou belief, the lwa communicate with humans through dreams and divination, and in turn are given offerings, including sacrificed animals. Vodou teaches that during ceremonies, the lwa possess specific practitioners, who during the possession are considered the chwal (horse) of the lwa. Through possessing an individual, Vodouists believe, the lwa can communicate with other humans, offering advice, admonishment, or healing. During the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries, enslaved West Africans brought their traditional religions with them. In the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which became the republic of Haiti in the early 19th century, the diasporic religion of Vodou emerged amid the mixing of different West African traditional religions and the influence of the French colonists' Roman Catholicism. From at least the 19th century, Haitian migrants took their religion to Louisiana, by that point part of the United States, where they contributed to the formation of Louisiana Voodoo, a religion that largely died out in the early 20th century. In the latter part of that century, Voodoo revivalist groups emerged in Louisiana, often incorporating both the lwa spirits of Haitian Vodou and the oricha spirits of Cuban Santería into their practices. EtymologyModern linguists trace the etymology of lwa to a family of Yoruba language words which include olúwa (god) and babalawo (diviner or priest).[2][3][4] The term lwa is phonetically identical to both a French term for law, loi, and a Haitian Creole term for law, lwa.[5] The early 20th-century writer Jean Price-Mars pondered if the term lwa, used in reference to Vodou spirits, emerged from their popular identification with the laws of the Roman Catholic Church.[2] In the early 21st century, the historian Kate Ramsey agreed that the phonetic similarity between the terms for the law and the Vodou spirits may not be "mere linguistic coincidence" but could reflect the complex interactions of African and French colonial cultures in Haiti.[5] Several spelling for lwa have been used. Early 20th-century writers on Haitian religion, such as Price-Mars, usually spelled the term loi.[2] During that century, writers like the American anthropologist Melville Herskovits favored the spelling loa,[2] although in 2008 the historian Jeffrey E. Anderson wrote that the spelling loa was typically found in older works on the topic, having fallen out of favor with scholarly writers.[6] The spelling lwa has been favored by more recent scholarly writers including Anderson,[6] Ramsey,[7] the anthropologist Karen McCarthy Brown,[8] the scholar of religious studies Leslie Desmangles,[9] and the Hispanic studies scholars Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert.[10] TheologyVodou teaches that there are over a thousand lwa.[11] They are regarded as the intermediaries of Bondyé, the supreme creator deity in Vodou.[12] Desmangles argued that by learning about the various lwas, practitioners come to understand the different facets of Bondyé.[11] Much as Vodouists often identify Bondyé with the Christian God, the lwa are sometimes equated with the angels of Christian cosmology.[13] The lwa are also known as the mystères, anges, saints, and les invisibles.[14] The lwa can offer help, protection, and counsel to humans, in return for ritual service.[15] They are thought of as having wisdom that is useful for humans,[16] although they are not seen as moral exemplars which practitioners should imitate.[8] Each lwa has its own personality,[14] and is associated with specific colors,[17] days of the week,[18] and objects.[14] The lwa can be either loyal or capricious in their dealings with their devotees;[14] Vodouists believe that the lwa are easily offended, for instance if offered food that they dislike.[19] When angered, the lwa are believed to remove their protection from their devotees, or to inflict misfortune, illness, or madness on an individual.[20]  Although there are exceptions, most lwa names derive from the Fon and Yoruba languages.[21] New lwa are nevertheless added to those brought from Africa;[22] practitioners believe that some Vodou priests and priestesses became lwa after death, or that certain talismans become lwa.[23] Vodouists often refer to the lwa residing in "Guinea", but this is not intended as a precise geographical location.[24] Many lwa are also understood to live under the water, at the bottom of the sea or in rivers.[18] Vodouists believe that the lwa communicate with humans through dreams and through the possession of human beings.[25] During rituals, the lwa are summoned through designs known as veve.[26] These are sketched out on the floor of the ceremonial space using cornmeal, ash, coffee grounds, or powdered eggshells.[27] The lwa are associated with specific Roman Catholic saints.[28] For instance, Azaka, the lwa of agriculture, is associated with Saint Isidore the farmer.[29] Similarly, because he is understood as the "key" to the spirit world, Papa Legba is typically associated with Saint Peter, who is visually depicted holding keys in traditional Roman Catholic imagery.[30] The lwa of love and luxury, Ezili Freda, is associated with Mater Dolorosa.[31] Damballa, who is a serpent, is often equated with Saint Patrick, who is traditionally depicted in a scene with snakes; alternatively he is often associated with Moses.[32] The Marasa, or sacred twins, are typically equated with the twin saints Cosmos and Damian.[33] Nanchon In Haitian Vodou, the lwa are divided into nanchon or "nations".[35] This classificatory system derives from the way in which enslaved West Africans were divided into "nations" upon their arrival in Haiti, usually based on their African port of departure rather than their ethno-cultural identity.[14] The nanchons are nevertheless not groupings based in the geographical origins of specific lwas.[36] The term fanmi (family) is sometimes used synonymously with "nation" or alternatively as a sub-division of the latter category.[37] It is often claimed that there are 17 nanchon, although few Haitians could name all of them.[38] Each is deemed to have its own characteristic ethos.[38] Among the more commonly known nanchon are the Wangol, Ginen, Kongo, Nago (or Anago), Ibo, Rada, and Petwo.[38] Of these, the Rada and the Petwo are the largest and most dominant.[39] The Rada derive their name from Arada, a city in the Dahomey kingdom of West Africa.[40] The Rada lwa are usually regarded as dous or doux, meaning that they are sweet-tempered.[41] The Petwo lwa are conversely seen as lwa chaud (lwa cho), indicating that they can be forceful or violent and are associated with fire;[41] they are generally regarded as being socially transgressive and subversive.[42] The Rada lwa are seen as being 'cool'; the Petwo lwa as 'hot'.[43] The Rada lwa are generally regarded as righteous, whereas their Petwo counterparts are thought of as being more morally ambiguous, associated with issues like money.[44] At the same time, the Rada lwa are regarded as being less effective or powerful than those of the Petwo nation.[44] The Petwo lwa derive from various backgrounds, including Creole, Kongo, and Dahomeyan.[45] In various cases, certain lwa can be absorbed from one nanchon into another; various Kongo and Ibo lwa have been incorporated into the Petwo nanchon.[38] Many lwa exist andezo or en deux eaux, meaning that they are "in two waters" and are served in both Rada and Petwo rituals.[41] Various lwas are understood to have direct counterparts in different nanchon; several Rada lwas for instance have Petwo counterparts whose names bear epithets like Flangbo (afire), Je-Rouge (Red-Eye), or Zarenyen (spider).[46] One example is the Rada lwa Ezili, who is associated with love, but who has a Petwo parallel known as Ezili Je-Rouge, who is regarded as dangerous and prone to causing harm.[46] Another is the Rada lwa Legba, who directs human destiny, and who is paralleled in the Petwo pantheon by Kafou Legba, a trickster who causes accidents that alter a person's destiny.[46] The Gede (also Ghede or Guede) family of lwa are associated with the realm of the dead.[47] The head of the family is Baron Samedi ("Baron Saturday").[48] His consort is Grand Brigitte;[49] she has authority over cemeteries and is regarded as the mother of many of the other Gede.[50] When the Gede are believed to have arrived at a Vodou ceremony they are usually greeted with joy because they bring merriment.[47] Those possessed by the Gede at these ceremonies are known for making sexual innuendos;[51] the Gede's symbol is an erect penis,[52] while the banda dance associated with them involves sexual-style thrusting.[53] RitualOfferings and animal sacrifice Feeding the lwa is of great importance in Vodou,[54] with rites often termed mangers-lwa ("feeding the lwa").[55] Offering food and drink to the lwa is the most common ritual within the religion, conducted both communally and in the home.[54] An oungan (priest) or manbo (priestess) will also organize an annual feast for their congregation in which animal sacrifices to various lwa will be made.[56] The choice of food and drink offered varies depending on the lwa in question, with different lwa believed to favour different foodstuffs.[57] Damballa for instance requires white foods, especially eggs.[58] Foods offered to Legba, whether meat, tubers, or vegetables, need to be grilled on a fire.[54] The lwa of the Ogu and Nago nations prefer raw rum or clairin as an offering.[54] A mange sèc (dry meal) is an offering of grains, fruit, and vegetables that often precedes a simple ceremony; it takes its name from the absence of blood.[59] Species used for sacrifice include chickens, goats, and bulls, with pigs often favored for petwo lwa.[55] The animal may be washed, dressed in the color of the specific lwa, and marked with food or water.[60] Often, the animal's throat will be cut and the blood collected in a calabash.[61] Chickens are often killed by the pulling off of their heads; their limbs may be broken beforehand.[62] The organs are removed and placed on the altar or vèvè.[62] The flesh will be cooked and placed on the altar, subsequently often being buried.[61] Maya Deren wrote that: "The intent and emphasis of sacrifice is not upon the death of the animal, it is upon the transfusion of its life to the lwa; for the understanding is that flesh and blood are of the essence of life and vigor, and these will restore the divine energy of the god."[63] Because Agwé is believed to reside in the sea, rituals devoted to him often take place beside a large body of water such as a lake, river, or sea.[64] His devotees sometimes sail out to Trois Ilets, drumming and singing, where they throw a white sheep overboard as a sacrifice to him.[65] The food is typically offered when it is cool; it remains there for a while before humans can then eat it.[66] The food is often placed within a kwi, a calabash shell bowl.[66] Once selected, the food is placed on special calabashes known as assiettes de Guinée which are located on the altar.[56] Offerings not consumed by the celebrants are then often buried or left at a crossroads.[67] Libations might be poured into the ground.[56] Vodouists believe that the lwa then consume the essence of the food.[56] Certain foods are also offered in the belief that they are intrinsically virtuous, such as grilled maize, peanuts, and cassava. These are sometimes sprinkled over animals that are about to be sacrificed or piled upon the vèvè designs on the floor of the peristil.[56] Possession Possession by the lwa constitutes an important element of Vodou.[68] It lies the heart of many of its rituals;[8] these typically take place in a temple called an ounfò,[69] specifically in a room termed the peristil or peristyle.[70] The person being possessed is referred to as the chwal or chual (horse);[71] the act of possession is called "mounting a horse".[72] Vodou teaches that a lwa can possess an individual regardless of gender; both male and female lwa can possess either men or women.[73] Although children are often present at these ceremonies,[74] they are rarely possessed as it is considered too dangerous.[75] While the specific drums and songs used are designed to encourage a specific lwa to possess someone, sometimes an unexpected lwa appears and takes possession instead.[76] In some instances a succession of lwa possess the same individual, one after the other.[77] The trance of possession is known as the crise de lwa.[78] Vodouists believe that during this process, the lwa enters the head of the chwal and displaces their gwo bon anj,[79] which is one of the two halves of a person's soul.[80] This displacement is believed to cause the chwal to tremble and convulse;[81] Maya Deren described a look of "anguish, ordeal and blind terror" on the faces of those as they became possessed.[82] Because their consciousness has been removed from their head during the possession, Vodouists believe that the chwal will have no memory of what occurs during the incident.[83] The length of the possession varies, often lasting a few hours but sometimes several days.[84] It may end with the chwal collapsing in a semi-conscious state;[85] they are typically left physically exhausted.[82] Some individuals attending the dance will put a certain item, often wax, in their hair or headgear to prevent possession.[86] Once the lwa possesses an individual, the congregation greet it with a burst of song and dance.[82] The chwal will typically bow before the officiating priest or priestess and prostrate before the poto mitan, a central pillar within the temple.[87] The chwal is often escorted into an adjacent room where they are dressed in clothing associated with the possessing lwa. Alternatively, the clothes are brought out and they are dressed in the peristil itself.[73] Once the chwal has been dressed, congregants kiss the floor before them.[73] These costumes and props help the chwal take on the appearance of the lwa.[88] Many ounfo have a large wooden phallus on hand which is used by those possessed by Ghede lwa during their dances.[89]  The chwal takes on the behaviour and expressions of the possessing lwa;[90] their performance can be very theatrical.[76] Those believing themselves possessed by the serpent Damballa, for instance, often slither on the floor, dart out their tongue, and climb the posts of the peristil.[91] Those possessed by Zaka, lwa of agriculture, will dress as a peasant in a straw hat with a clay pipe and will often speak in a rustic accent.[92] The chwal will often then join in with the dances, dancing with anyone whom they wish to,[82] or sometimes eating and drinking.[88] Sometimes the lwa, through the chwal, will engage in financial transactions with members of the congregation, for instance by selling them food that has been given as an offering or lending them money.[93] Possession facilitates direct communication between the lwa and its followers;[82] through the chwal, the lwa communicates with their devotees, offering counsel, chastisement, blessings, warnings about the future, and healing.[94] Lwa possession has a healing function, with the possessed individual expected to reveal possible cures to the ailments of those assembled.[82] Clothing that the chwal touches is regarded as bringing luck.[95] The lwa may also offer advice to the individual they are possessing; because the latter is not believed to retain any memory of the events, it is expected that other members of the congregation will pass along the lwa's message.[95] In some instances, practitioners have reported being possessed at other times of ordinary life, such as when someone is in the middle of the market,[96] or when they are asleep.[97] HistoryDuring the closing decades of the 20th century, attempts were made to revive Louisiana Voodoo, often by individuals drawing heavily on Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería in doing so.[98] Among those drawing on both Vodou lwa and Santería oricha to create a new Voodoo was the African American Miriam Chamani, who established the Voodoo Spiritual Temple in the French Quarter of New Orleans in 1990.[99] Another initiate of Haitian Vodou, the Ukrainian-Jewish American Sallie Ann Glassman, launched an alternative group, La Source Ancienne, in the city's Bywater neighborhood.[100] A further Haitian Vodou initiate, the Louisiana Creole Ava Kay Jones, also began promoting a form of Louisiana Voodoo.[101] ListVodouisants will sometimes comment that there are over a thousand lwas, most of whom are not known to humans.[11] Of these, the names of at least 232 have been recorded.[102] The large number of lwas found in Vodou contrasts with the Cuban religion of Santería, where only 15 orichas (spirits) have gained prominence among its followers.[102]

In culture

See alsoReferencesNotesCitations

Sources

Further readingPrimary sources

External links |