|

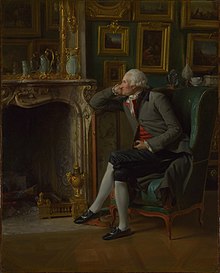

Luc-Vincent Thiéry Luc-Vincent Thiéry (1734–1822) was a French lawyer and author, best known for his publications about Paris. BiographyLittle is known about Luc-Vincent Thiéry's life. There are few sources and the information is sparse. He was born in Paris on 27 September 1734 and died in Soissons on 12 January 1822. Thiéry was interested in art, architecture and literature. He was a member of several literary societies.[1][2] PublicationsLuc-Vincent Thiéry's different guides on the city of Paris were published between 1783 and 1796. His most famous guide is the Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable (Guide for connoisseurs and foreign travelers to Paris, or analysed description of this city, its suburbs and everything that is remarkable about them). Although published twice, it's the first edition from 1787 for which he is still remembered today. First editionIn the years 1783, 1784 and 1785, Thiéry's publisher, Libraire Hardouin à Paris, published his Almanach du Voyageur à Paris. With the edition of 1785, the editor announced that a new and more comprehensive guide in two volumes will follow. Two years later, in January 1787, together with an updated version of the Almanach du Voyageur à Paris, the first edition of the Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable was published. The publication was dedicated to Pierre-Charles Laurent de Villedeuil.[3][2] In 1788 a new guide was published, similar in form to the Almanach du Voyageur à Paris, but with a classification of the subjects in alphabetical order. However, this new publication, titled Le Voyageur à Paris, was more or less just an excerpt from the Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable. It was divided into two parts and contained a small map of the city of Paris. In 1789, the publication was reissued with almost identical content. Unlike previous publications, the introductory pages included now a personal message from the editor and an events calendar for Paris for that year as well as the mention of new places of interest and what significant changes have occurred in this context over the past year. In 1790, the last edition of the Voyageur à Paris was published. It only differed from the previous ones by the introductory pages, which corrected what had been completely outdated by the French Revolution.[3][2] Final editionThe Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable, was published a second time in 1796 under the title Paris tel qu'il était avant la Révolution by the publisher Libraire & Commissionnaire Delaplace à Paris. The publisher used the copies that remained from the 1787 edition. The two editions were almost identical, including the printing errors. Only the foreword pages were recomposed and the font for these pages was replaced with looser and less careful typography. In addition, the newly added pages were printed on lower quality paper.[3][2] Research on site: The private world of the hôtels particuliers Luc-Vincent Thiéry has documented himself with specialists for his publications, such as the secretaries of the academies, the rector of the university, the priests of the churches, the superiors of the convents and the architects of the monuments. He also contacted the owners of some of the most famous hôtels particuliers. Some of them granted him privileged access to their private world and thus their art collections. Luc-Vincent Thiéry confirms in the preface of his Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable, published in 1787: "The various works of art in the cabinets of curiosities could be viewed under the eyes of their owners, the amateurs propriétaires, who gave their consent."[5][2] Baron de BesenvalOne of the personalities who granted Thiéry access to his private world and thus his furniture, porcelain and art collection, was Pierre Victor, Baron de Besenval de Brunstatt, a Swiss military officer in French service, who owned the Hôtel de Besenval. Thiéry took his chance and, accompanied by the baron, took an extensive tour of this hôtel particulier on the Rue de Grenelle. He describes his tour of the Hôtel de Besenval in all details in his Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable, published in 1787. Thiéry's report reads like an inventory. He meticulously describes where which picture hangs or which piece of furniture is in which room, who made it or what its provenance is. Of particular interest to Thiéry was the baron's nymphaeum, a unique extravagance.[4] A reference workThanks to the precise descriptions, Thiéry's guide is still a reference work for museums, art dealers and auction houses today. Rediscovered pieces from the collection of the Baron de Besenval A few years ago, some valuable pieces from the Baron de Besenval's former collection were auctioned. Thanks to Thiéry's guide, and the Baron de Besenval's 1795 collection sale catalogue by the auctioneer Alexandre Joseph Paillet, these pieces could be identified as pieces that previously belonged to the collection of Pierre Victor de Besenval. One of the pieces was the former writing desk of the Baron de Besenval, which was sold at Christie's in London on 25 May 2021, as lot 30, for EUR462,500. Thiéry describes this writing desk in detail in his 1787 guide. He even mentions that it was placed in the baron's bedroom. However, the highlight in this context was sold two months later, on 8 July 2021, by the same auction house: The Baron de Besenval Garniture, a six-piece set made of Chinese celadon porcelain mounted with French gilt-bronze. Part of it can be seen on the mantelpiece in the iconic portrait of the Baron de Besenval, Le Baron de Besenval dans son salon de compagnie, painted by Henri-Pierre Danloux in 1791. The celadon porcelain garniture was sold in three lots (lots 4, 5 and 6) for a total of GBP1,620,000.[10][11][12][13][14] Years earlier, it was this iconic portrait of the Baron de Besenval itself that was sold by Sotheby’s in New York on 27 May 2004, as lot 35, for US$2,472,000. It shows the baron in his picture cabinet at the Hôtel de Besenval to which Thiéry had privileged access and the contents of which he describes meticulously in his 1787 publication. According to Thiéry, the baron's cabinet was primarily renowned for the remarkable collection of contemporary and earlier pictures of the Flemish, Italian and French schools. Thiéry mentions, amongst others, a painting by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, which was almost certainly the original version of La Gimblette. On 10 August 1795, this painting was sold by the auctioneer Alexandre Joseph Paillet in Paris, as lot 77, as part of the auction of the Baron de Besenval's collection. Today the painting is considered lost. However, there is an engraving based on this painting, executed by Charles Bertony in 1783 and dedicated to the Baron de Besenval.[9][14][15][16] Luc-Vincent Thiéry also reports a beautiful commode in the baron's bedroom, the front of which is decorated with inlaid stone reliefs of flowers and fruits (pietra dura). This commode has been proven to be identical to the commode à vantaux on display in the Green Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace.[14][17] References

|