|

Louisa Atkinson

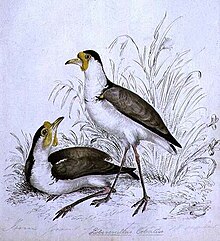

Caroline Louisa Waring Calvert (née Atkinson; 25 February 1834 – 28 April 1872) was an early Australian writer, botanist and illustrator. While she was well known for her fiction during her lifetime, her long-term significance rests on her botanical work.[1] She is regarded as a ground-breaker for Australian women in journalism and natural science, and is significant in her time for her sympathetic references to Aboriginal Australians in her writings and her encouragement of conservation. LifeLouisa, as she was generally known, was born on her parents' property "Oldbury", Sutton Forest, about 3 mi (4.8 km) from Berrima, New South Wales, and was their fourth child. Her father, James Atkinson, was the author of an early Australian book, An Account of the State of Agriculture and Grazing in New South Wales, published in 1826. He died in 1834, when Louisa was only 8 weeks old.[2] Louisa was a somewhat frail child with a heart defect, and so was educated by her mother, Charlotte Barton, herself the author of Australia's first children's book, A Mother's Offering to her Children. Her mother remarried, but this second husband, George Barton, a family friend, "became violently and irrevocably insane not long after the marriage"[3] resulting in the family needing to leave "Oldbury". She lived most of her life in Kurrajong Heights in a home called Fernhurst that was built by her mother.[4] Prior to that she had lived briefly in Shoalhaven and Sydney.[2] She became an active member of the community, operating as an unpaid scribe for the unlettered people of the district, a confidante of children, and a helper of the old and the sick. She also organised and taught in the district's first Sunday School.[4] Louisa and her mother returned to "Oldbury" in 1865, with her mother dying there in 1868.[5] On 11 March 1869, she married James Snowden Calvert (1825–84), a survivor of Leichhardt's expedition of 1844–5 and also interested in botany.[6] He was, at the time, manager of Cavan station at Wee Jasper near Yass.[5] She died at Swanton, near "Oldbury", in 1872, 18 days after the birth of her daughter, Louise Snowden Annie. She was buried in the Atkinson family vault at All Saints' Church, Sutton Forest. Her obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald described her as: "This excellent lady, who has been cut down like a flower in the midst of her days, was highly distinguished for her literary and artistic attainments, as well as for the Christian principles and expansive charity which marked her career".[7] According to Chisholm, she is also credited with being "something of a pioneer in dress reform: the long skirts of the period were simply a nuisance in scrubby areas and so this woman used, both when rambling and pony riding, attire [trousers] which is said to have aroused 'some twitterings in the ranks of the colonial Mrs Grundy'."[6] Clarke writes that she was joined in this behaviour by Mrs Selkirk, a local doctor's wife.[8]  Cowanda  The Possum  Sandpipers  Xanthosia atkinsoniana Botanist, naturalist and artistLouisa is acknowledged as a leading botanist who discovered new plant species in the Blue Mountains and Southern Highlands region of New South Wales, and she championed the cause of conservation during a period of rapid land-clearing. Her botanical interest is, in part, credited to her home-schooling by her mother, who was herself artistic and interested in natural history.[6][9] She undertook botanical excursions in areas remote from where she lived, such as the Illawarra, but she became particularly well informed on the flora in Kurrajong and environs, such as the Grose Valley, Mt Tomah and Springwood, where she spent much of her life. She collected specimens extensively for Rev. Dr. William Woolls, a well-known teacher and amateur botanist, and Ferdinand von Mueller.[1] Lawson writes that von Mueller's work was aided by many amateur naturalists in Australia, but that Atkinson's contribution is worthy of particular note "for the quality of its information, its scholarly commitment, its enthusiasm and persistence over time, its geographical range, its local depth, its robustness and liveliness of descriptive record, its sense of primary exploration, its sheer inventiveness".[3] She is commemorated in the Loranthaceous genus Atkinsonia, and in the species Erechtites atkinsoniae, Epacris calvertiana, Helichrysum calvertianum, Xanthosia atkinsoniana and Doodia atkinsonii. Her collection of over 800 botanical specimens is held at the National Herbarium of Victoria.[10][11] By the 1860s Atkinson was becoming aware of the impact of European agriculture on native flora. She wrote about this on several occasions, making such statements as "It needs no fertile imagination to foresee that in, say, half-a-century's time, tracts of hundreds of miles will be treeless".[3] She is also well regarded as a botanical artist,[12] was interested in zoology and was a competent taxidermist.[1] Her botanical art was unusual for its diversity: it included animals, birds, insects, reptiles and landscapes.[13][9] She popularised science and wrote for The Sydney Morning Herald and the Horticultural Magazine. WriterIn another claim to fame, Louisa is credited as the first Australian-born woman to have a novel published in Australia, Gertrude the Emigrant (1857), for which she used the name "An Australian woman". She was 23 years old.[14] Contemporary critic, G. B. Barton, described the novel as follows: "The scene is laid wholly in the Colony, principally in the bush; and nowhere are the peculiar features of bush life more accurately or graphically pourtrayed [sic]. The tale abounds in incident, the characters are skilfully drawn, and the literary execution is quite equal to that of ordinary novels".[15] She was also the first author to illustrate her own work.[2] Her second novel, Cowanda, The Veteran's Grant (1859) had a cover design by colonial artist S. T. Gill.[5] Various other stories by her were serialised in The Sydney Mail. She was deeply religious and her fiction, which can generally be described as "Victorian romance-melodrama",[3] conveyed simple moral messages through "intrusive explicit moralising".[3] Despite this, her novels are significant because "they are the first novels written by a native-born Australian woman; they offer, however roughly, a vigorously sustained depiction of Australian colonial life; and they offer a particular colonial, female perspective actively attempting to modify imported English values".[3] Lawson also argues that, through her personal experience, Atkinson is able to record in her fiction "a female perspective on an infant white Australia, both in its rushed ad hoc urban development and its equally ad hoc muddled pastoral growth".[3] The Jessie Street National Women's Library states that her work is important for promoting the rights of women and children[2] and, in fact, Lawson suggests that "it is possible to see Atkinson as our first true humanist-democrat in fiction since she addresses the same observant analysis and compassion to white and black characters and to women as well as men".[3] In addition to fiction, Atkinson also wrote natural science articles, and was 19 when, in 1853, the Illustrated Sydney News published her first illustrated articles, Nature Notes of the Month with Illustrations. She was the first woman in Australia to have a long-running series of articles published in a major newspaper.[2] This was a series of natural history sketches titled "A Voice from the Country". They appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Sydney Mail from 12 December 1859 and ran for over 10 years.[16][8] They were "simply informative and popularising" with a "straightforward educational tone and intention".[3] An editorial note attached to the posthumous publication of her last story, Tessa's Resolve, states that these articles "are looked upon somewhat as authorities in matters relating to Australian natural history and botany".[17] Using the signature 'LA', becoming 'LC' in 1869, her illustrated, but more scientific, articles on flora and fauna were published in the Horticultural Magazine from 1864 to 1870.[18][19] Atkinson Street, in the Canberra suburb of Cook, is named in her honour.[20] See alsoWorks

Manuscript sources

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||