|

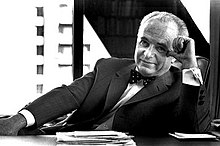

Louis O. Kelso

Louis Orth Kelso (/ˈkɛlsoʊ/; December 4, 1913 – February 17, 1991) was a political economist, corporate and financial lawyer, author, lecturer and merchant banker who is chiefly remembered today as the inventor and pioneer of the employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), invented to enable working people without savings to buy stock in their employer company and pay for it out of its future dividend yield.[1] BiographyHe was born on December 4, 1913, in Denver, Colorado.[1] Kelso began to think seriously about economics in 1931, during the Great Depression. He was determined to launch his own investigation into the cause of a phenomenon no one was able to explain to his satisfaction. This quest took him to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where in 1937 he was graduated with a B.S. degree in business administration and finance; he went on to law school in Boulder, receiving a J.D. in 1938. He then joined a Denver law firm, Pershing, Bosworth, Dick & Dawson from 1938 to 1942.[1] Then came Pearl Harbor. Kelso was commissioned in the U.S. Naval Service, and assigned to intelligence duty first in San Francisco and then in the Canal Zone. Working tropical hours, Kelso used his free afternoons to work on his seminal manuscript, The Fallacy of Full Employment. With the war over, the completed manuscript in his footlocker, the Navy sent him back to civilian life in 1946. But 1946 was also the year the Congress passed the Full Employment Act. This legislation, still in force, defines economic policy in the United States 170 years after the official birth of the Industrial Revolution as the right to a job. Kelso concluded that the time for his ideas had not yet come. He then taught constitutional law at University of Colorado at Boulder. He then moved to San Francisco, California. There he became a law partner with Kelso, Cotton, Seligman & Ray.[1] He died on February 17, 1991, at the Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, California.[1] Development of ESOPsKelso created the ESOP in 1956 to enable the employees of a closely held newspaper chain to buy out its retiring owners. Two years later Kelso and his co-author, the philosopher Mortimer J. Adler, explained the macro-economic theory on which the ESOP is based in The Capitalist Manifesto (Random House, 1958). In The New Capitalists (Random House, 1961), the two authors present Kelso's financial tools for democratizing capital ownership in a private property, market economy. These ideas were further elaborated and refined in Two-Factor Theory: The Economics of Reality (Random House, 1967) and Democracy and Economic Power: Extending the ESOP Revolution Through Binary Economics (1986, Ballinger Publishing Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts; reprinted 1991, University Press of America, Lanham, Maryland), both co-authored by Patricia Hetter Kelso, his collaborator since 1963. Kelso's next financing innovation, the Consumer Stock Ownership Plan (CSOP), in 1958 enabled a consortium of farmers in the Central Valley to finance and start up an anhydrous ammonia fertilizer plant. Despite fierce opposition from the major oil companies who dominated the industry, Valley Nitrogen Producers was a resounding success. Substantial dividends first paid for the stock and then drastically reduced fertilizer costs for the farmer-shareholders. Kelso regarded the ESOP and CSOP as pragmatic proof that his revolutionary revision of classical economic theory, and the financial techniques he derived from this new perspective, were sound and workable in the economic and business world. Kelso gained that worldly knowledge from his work as a corporate and financial lawyer, and later as senior partner in the law firm he founded. He was further motivated by his conviction that lawyers had a special responsibility to maintain and improve society's institutions in the light of its democratic values. He further believed that the business corporation was society's greatest social invention and that its executives had a fiduciary responsibility in exercising its vast power. Kelso long believed that he had not originated a new economic theory but only discovered a vital fact that the classical economists had somehow overlooked. This fact was the key to understanding why the private property, free market economy was notoriously unstable, pursuing a roller coaster course of exhilarating highs and terrifying descents into economic and financial collapse. This missing fact, which Kelso had uncovered over years of intensive reading, research and thought, drastically modifies the classical paradigm which has dominated formal economics since Adam Smith. It concerns the effect of technological change on the distributive dynamics of a private property, free market economy. Technological change, Kelso concluded, makes tools, machines, structures and processes ever more productive while leaving human productivity largely unchanged. The result is that primary distribution through the free market economy (whose distributive principle is "to each according to his production") delivers progressively more market-sourced income to capital owners and progressively less to workers who make their contributions through labor. Differential productiveness over time concentrates market-sourced income in the hands of those who will not recycle it back through the market as payment for consumer goods and services. They already have most of what they want and need, so they invest their excess in new productive power. This is the source of the distributional bottleneck which makes the private property, free market economy ever more dysfunctional. The symptoms of dysfunction are capital concentration and inadequate consumer demand, the effects of which translate into poverty and economic insecurity for the majority of people who depend entirely on wage income and cannot survive more than a week or two without a paycheck. And since, as Adam Smith laid down, economic demand begins with the consumer and consumer purchasing power, the production side of the economy is under-nourished and hobbled. All of Kelso's financing tools and economic proposals are designed to correct the imbalance between production and consumption at its source, in conformity with the private property/free market principles identified by Smith and his followers. In a biographical summary written for the National Center for Employee Ownership in 1988, Kelso described "the area in which first I alone, and then, beginning about 25 years ago, Patricia and I, have made our contribution to the world of economics and corporate (and other) finance. The Kelso contribution lies partly in the area of macro-economic discovery, and partly in practical ways to implement and make good use of those discoveries in human affairs." Although going along with Random House's cold-war title, The Capitalist Manifesto, Kelso and Adler believed that capitalist was not the right term. But they could not come up with a better one. In their book they had called Kelso's new concept the theory of capitalism. Later Kelso and Hetter, wrestling with the same semantic problem, came up with the term universal capitalism. Not until after their last book was already in print did Kelso discover the term they had been searching for all along: binary economics. Kelso & CompanyIn 1971, Louis Kelso founded Kelso Bangert & Company as a merchant bank that would be both an advisor and investor in mergers and acquisitions involving employee stock ownership plans. The firm, which would later come to be known as Kelso & Company, would transition toward private equity investments in the late 1970s and would raise its first private equity fund in 1980. Today Kelso & Company is a $10 billion private equity firm and was among the 50 largest private equity firms globally. Quotes

Publications

Other writings by Louis O. Kelso

Other writings by Louis O. Kelso (with Patricia Hetter Kelso)

See alsoReferences

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||