|

Lion's Mound

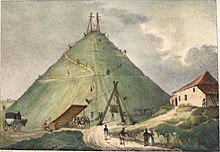

The Lion's Mound (French: Butte du Lion, lit. "Lion's Hillock/Knoll"; Dutch: Leeuw van Waterloo, lit. "Lion of Waterloo") is a large conical artificial hill in the municipality of Braine-l'Alleud, Walloon Brabant, Belgium. King William I of the Netherlands ordered its construction in 1820, and it was completed in 1826. It commemorates the spot on the battlefield of Waterloo where the king's elder son, Prince William of Orange, is presumed to have been wounded on 18 June 1815, as well as the Battle of Quatre Bras, which had been fought two days earlier. The hill offers a vista of the battlefield, and is the anchor point of the associated museums and taverns in the surrounding Lion's Hamlet (French: Hameau du Lion; Dutch: Gehucht met de Leeuw).[1] Visitors who pay a fee may climb up the mound's 226 steps,[2] which lead to the statue and its surrounding overlook (where there are maps documenting the battle, along with observation telescopes); the same fee also grants admission to see the painting Waterloo Panorama.[3] HistoryDesign and construction The Lion's Mound was designed by the royal architect Charles Vander Straeten, at the behest of King William I of the Netherlands, who wished to commemorate the location on the battlefield of Waterloo where a musket ball hit the shoulder of his elder son, King William II of the Netherlands (then Prince of Orange), and knocked him from his horse during the battle, on 18 June 1815.[4] It is also a memorial of the Battle of Quatre Bras, which had been fought two days earlier, on 16 June 1815. The engineer Jean-Baptiste Vifquain conceived of it as a symbol of the Allied victory rather than as glorifying any sole individual.[5] The construction took place between 1823 and October 1826. The lion's statue was hoisted and placed on its pedestal at the top of the mound on the evening of 28 October 1826.[6] Though tourism to the site had already begun the day after the battle, with Captain Mercer noting that, on 19 June 1815, "a carriage drove on the ground from Brussels, the inmates of which, alighting, proceeded to examine the field",[7] the monument's success only dates from the second half of the 19th century. In 1832, when Marshal Gérard's French troops passed through Waterloo to support the siege of the Citadel of Antwerp, which was still held by the Dutch, the lion's statue was almost toppled by the French soldiers. They even broke its tail.[8] It was not until 1863–64 that the promenade at the top of the hill was developed and the staircase built. Later historyOn 14 January 1999, landslides occurred on the Lion's Mound on the side of the Panorama building.[9] Similar damage occurred in 1995 and was repaired by driving 650 micro-piles.[10] On 21 May 2015, the Waterloo 1815 Memorial was inaugurated to mark the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, at a cost of around €40 million, including renovation of adjacent structures.[11][12] Since then, there has been a fee for access to the Lion's Mound, which is only accessible via the nearby museum. On 28 February 2019, a concession contract was signed entrusting the site's tourism operation to the French company Kléber Rossillon until 2035, in return for an annual fee of €365,000 and two variable fees on turnover.[13][14] DescriptionMound The mound itself is a regular cone of earth, 43 metres (141 ft) in height, 169 metres (554 ft) in diameter, and 520 metres (1,710 ft) in circumference. This huge man-made hill was constructed using 300,000 cubic metres (390,000 cu yd) of earth taken from the ridge at the centre of the British line, effectively removing the fields between La Haye Sainte farm and the southern bank of Duke of Wellington's sunken lane. Victor Hugo, in his novel Les Misérables, wrote that the Duke of Wellington visited the site two years after the mound's completion and said, "They have altered my field of battle!":

The alleged remark by Wellington about the alteration of the battlefield, as described by Hugo, was never documented, however.[16] Statue A colossal cast iron statue of a lion standing upon a stone-block pedestal surmounts the hill. Jean-Louis Van Geel (1787–1852) sculpted this Leo Belgicus, which closely resembles the 16th-century Medici lions. The lion is represented on the crests of both the Royal Arms of England and the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom, as well as on the personal coat of arms of the monarch of the Netherlands, and symbolises courage. Its right front paw is upon a sphere, signifying global victory.  The statue is accessible by a staircase of 226 steps.[2] It weighs 28 tonnes (62,000 lb), has a height of 4.45 metres (14.6 ft) and a length of 4.5 metres (15 ft). William Cockerill's iron foundry in Liège cast the statue in sections; a canal barge brought those pieces to Brussels; from there, heavy horse-drays drew the parts to Mont-St-Jean, a low ridge south of Waterloo. There is a legend that the foundry melted down brass from cannons that the French had left on the battlefield, in order to cast the metal lion. In reality, the foundry made nine separate partial casts in iron and assembled those components into one statue at the monument site. See also

ReferencesFootnotes

Citations

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Lion of Waterloo.

|

||||||||||||||||||