|

Laws of CricketThe Laws of Cricket is a code that specifies the rules of the game of cricket worldwide. The earliest known code was drafted in 1744. Since 1788, the code has been owned and maintained by the private Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in Lord's Cricket Ground, London. There are currently 42 Laws (always written with a capital "L"), which describe all aspects of how the game is to be played. MCC has re-coded the Laws six times, each with interim revisions that produce more than one edition. The most recent code, the seventh, was released in October 2017; its 3rd edition came into force on 1 October 2022.[1] Formerly cricket's official governing body, the MCC has handed that role to the International Cricket Council (ICC). But MCC retains copyright of the Laws and remains the only body that may change them, although usually this is only done after close consultation with the ICC and other interested parties such as the Association of Cricket Umpires and Scorers. Cricket is one of the few sports in which the governing principles are referred to as "Laws" rather than as "rules" or "regulations". In certain cases, however, regulations to supplement and/or vary the Laws may be agreed for particular competitions as required. Those applying to international matches (referred to as "playing conditions") can be found on the ICC's website.[2] HistoryOral traditionThe origin of cricket is uncertain and it was first definitely recorded at Guildford in the 16th century. It is believed to have been a boys' game at that time but, from early in the 17th century, it was increasingly played by adults. Rules as such existed and, in early times, would have been agreed orally and subject to local variations. Cricket in the late 17th century became a betting game attracting high stakes and there were instances of teams being sued for non-payment of wagers they had lost.[3][4][5] Articles of AgreementIn July and August 1727, two matches were organised by stakeholders Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond and Alan Brodrick, 2nd Viscount Midleton. References to these games confirm that they drew up Articles of Agreement between them to determine the rules that must apply in their contests.[6] The original handwritten articles document drawn up by Richmond and Brodrick has been preserved. It is among papers which the West Sussex Record Office (WSRO) acquired from Goodwood House in 1884.[7] This is the first time that rules are known to have been formally agreed, their purpose being to resolve any problems between the patrons during their matches. The concept, however, was to attain greater importance in terms of defining rules of play as, eventually, these were codified as the Laws of Cricket.[8] The Articles are a list of 16 points, many of which are easily recognised despite their wording as belonging to the modern Laws of Cricket, for example: (a) a Ball caught, the Striker is out; (b) when a Ball is caught out, the Stroke counts nothing; (c) catching out behind the Wicket allowed.[6] Points that differ from the modern Laws (use of italics is to highlight the differences only): (a) the wickets shall be pitched at twenty three yards distance from each other; (b) that twelve Gamesters shall play on each side; (c) the Batt Men for every one they count are to touch the Umpire's Stick; (d) no Player shall be deemed out by any Wicket put down, unless with the Ball in Hand. In modern cricket: (a) the pitch is 22 yards long; (b) the teams are eleven-a-side; (c) runs were only completed if the batsman touched the umpire's stick (which was probably a bat) and this practice was eventually replaced by the batsman having to touch the ground behind the popping crease; (d) run outs no longer require the ball to be in hand.[6][9] 1744 codeThe earliest known code of Laws was enacted in 1744 but not actually printed, so far as it is known, until 1755. They were possibly an upgrade of an earlier code and the intention must have been to establish a universal codification. The Laws were drawn up by the "noblemen and gentlemen members of the London Cricket Club", which was based at the Artillery Ground, although the printed version in 1755 states that "several cricket clubs" were involved, having met at the Star and Garter in Pall Mall. A summary of the main points:

The 1744 Laws do not say the bowler must roll (or skim) the ball and there is no mention of prescribed arm action so, in theory, a pitched delivery would have been legal, though potentially controversial. Underarm pitching is believed to have begun in the early 1760s when the Hambledon Club was rising to prominence. The modern straight bat was introduced as a consequence, replacing the old "hockey stick" bat which was good for hitting a ball on the ground but not for addressing a ball on the bounce.[10] In 1771, an incident on the field of play led to the creation of a new Law which remains extant. In a match between Chertsey and Hambledon at Laleham Burway, the Chertsey all-rounder Thomas White used a bat that was the width of the wicket. There was no rule in place to prevent this action and so all the Hambledon players could do was register a formal protest which was signed by Thomas Brett, Richard Nyren and John Small, the three leading Hambledon players. As a result, it was decided by the game's lawmakers that the maximum width of the bat must be four and one quarter inches; this was included in the next revision of the Laws and it remains the maximum width. 1774 code On Friday, 25 February 1774, the Laws were revised by a committee meeting at the Star and Garter. Chaired by Sir William Draper, the members included prominent cricket patrons the 3rd Duke of Dorset, the 4th Earl of Tankerville, Charles Powlett, Philip Dehany and Sir Horatio Mann. The clubs and counties represented were Kent, Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex, Middlesex and London. A summary of the main points added in the 1774 code:

The main innovation was the introduction of leg before wicket (lbw) as a means of dismissal. The practice of stopping the ball with the leg had arisen as a negative response to the pitched delivery. As in 1744, there is nothing about the bowler's delivery action. The maximum width of the bat was confirmed following the incident in 1771. As in 1744, the 1774 code asserted that "the stumps must be twenty-two inches, the bail six inches long". There were only two stumps then, with a single bail. At the Artillery Ground on 22–23 May 1775, a lucrative single wicket match was played between Five of Kent (with Lumpy Stevens) and Five of Hambledon (with Thomas White).[11] Kent batted first and made 37 to which Hambledon replied with 92, including 75 by John Small. In their second innings, Kent scored 102, leaving Hambledon a target of 48 to win. Small batted last of the Hambledon Five and needed 14 more to win when he went in. He duly scored the runs and Hambledon won by 1 wicket but a great controversy arose afterwards because, three times in the course of his second innings, Small was beaten by Lumpy only for the ball to pass through the two-stump wicket each time without hitting the stumps or the bail.[12] As a result of Lumpy's protests, the middle stump was introduced, although it was some years before its use became universal.[13] 1788 codeMCC was founded in 1787 and immediately assumed responsibility for the Laws, issuing a new version on 30 May 1788 which was called "The LAWS of the NOBLE GAME of CRICKET as revised by the Club at St. Mary-le-bone".[14] The third Law stated: "The stumps must be twenty-two inches out of the ground, the bail six inches in length". These were the overall dimensions and the requirement for a third stump was unspecified, indicating that its use was still not universal.[15] The 1788 code is much more detailed and descriptive than the 1774 code but, fundamentally, they are largely the same. The main difference was in the wording of the lbw Law. In 1774, this said that the batsman is out if, with design, he prevents the ball hitting the wicket with his leg. In 1788, the "with design" clause was omitted and a new clause was introduced that the ball must have pitched straight.[16] Also in 1788, protection of the pitch was first included in the Laws. By mutual consent between the teams, the pitch could be rolled, watered, covered and mown during a match and the use of sawdust was authorised. Previously, pitches were left untouched during a match.[16] Later MCC codesMCC has revised the Laws periodically, usually within the same code, but at times they have decided to publish an entirely new code:

Significant changes to the Laws since 1788Changes to the Laws did not always coincide with the publication of a new code and some of the most important changes were introduced as revisions to the current code and, therefore, each code has more than one version.

The Laws todayStarting on 1 October 2017, the current version of the Laws are the "Laws of Cricket 2017 Code" which replaced the 6th Edition of the "2000 Code of Laws". Custodianship of the Laws remains one of MCC's most important roles. The ICC still relies on MCC to write and interpret the Laws, which are the responsibility of MCC's Laws sub-committee. The process in MCC is that the sub-committee prepares a draft which is passed by the main committee. Certain levels of cricket, however, are subject to playing conditions which can differ from the Laws. At international level, playing conditions are implemented by the ICC; at domestic level by each country's board of control. The code of Laws consists of:

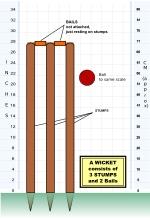

Starting from the third edition of the 2017 version of the code, the term "batter" was substituted from the term "batsman", to make the laws use gender-neutral terminology.[28][29][30] Setting up the gameThe first 12 Laws cover the players and officials, basic equipment, pitch specifications and timings of play. These Laws are supplemented by Appendices B, C and D (see below). Law 1: The players. A cricket team consists of eleven players, including a captain. Outside of official competitions, teams can agree to play more than eleven-a-side, though no more than eleven players may field.[31] Law 2: The umpires. There are two umpires, who apply the Laws, make all necessary decisions, and relay the decisions to the scorers. While not required under the Laws of Cricket, in higher level cricket a third umpire (located off the field, and available to assist the on-field umpires) may be used under the specific playing conditions of a particular match or tournament.[32] Law 3: The scorers. There are two scorers who respond to the umpires' signals and keep the score.[33]  Law 4: The ball. A cricket ball is between 8.81 and 9 inches (22.4 cm and 22.9 cm) in circumference, and weighs between 5.5 and 5.75 ounces (155.9g and 163g) in men's cricket. A slightly smaller and lighter ball is specified in women's cricket, and slightly smaller and lighter again in junior cricket (Law 4.6). Only one ball is used at a time, unless it is lost, when it is replaced with a ball of similar wear. It is also replaced at the start of each innings, and may, at the request of the fielding side, be replaced with a new ball, after a minimum number of overs have been bowled as prescribed by the regulations under which the match is taking place (currently 80 in Test matches).[34] The gradual degradation of the ball through the innings is an important aspect of the game. Law 5: The bat. The bat is no more than 38 inches (96.52 cm) in length, no more than 4.25 inches (10.8 cm) wide, no more than 2.64 inches (6.7 cm) deep at its middle and no deeper than 1.56 inches (4.0 cm) at the edge. The hand or glove holding the bat is considered part of the bat. Ever since the ComBat incident, a highly publicised marketing attempt by Dennis Lillee, who brought out an aluminium bat during an international game, the Laws have provided that the blade of the bat must be made of wood.[35]  Law 6: The pitch. The pitch is a rectangular area of the ground 22 yards (20.12 m) long and 10 ft (3.05 m) wide. The Ground Authority selects and prepares the pitch, but once the game has started, the umpires control what happens to the pitch. The umpires are also the arbiters of whether the pitch is fit for play, and if they deem it unfit, with the consent of both captains can change the pitch. Professional cricket is almost always played on a grass surface. However, in the event a non-turf pitch is used, the artificial surface must have a minimum length of 58 ft (17.68 m) and a minimum width of 6 ft (1.83 m).[36] Law 7: The creases. This Law sets out the dimensions and locations of the creases. The bowling crease, which is the line the stumps are in the middle of, is drawn at each end of the pitch so that the three stumps at that end of the pitch fall on it (and consequently it is perpendicular to the imaginary line joining the centres of both middle stumps). Each bowling crease should be 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) in length, centred on the middle stump at each end, and each bowling crease terminates at one of the return creases. The popping crease, which determines whether a batter is in his ground or not, and which is used in determining front-foot no-balls (see Law 21), is drawn at each end of the pitch in front of each of the two sets of stumps. The popping crease must be 4 feet (1.22 m) in front of and parallel to the bowling crease. Although it is considered to have unlimited length, the popping crease must be marked to at least 6 feet (1.83 m) on either side of the imaginary line joining the centres of the middle stumps. The return creases, which are the lines a bowler must be within when making a delivery, are drawn on each side of each set of the stumps, along each sides of the pitch (so there are four return creases in all, one on either side of both sets of stumps). The return creases lie perpendicular to the popping crease and the bowling crease, 4 feet 4 inches (1.32 m) either side of and parallel to the imaginary line joining the centres of the two middle stumps. Each return crease terminates at one end at the popping crease but the other end is considered to be unlimited in length and must be marked to a minimum of 8 feet (2.44 m) from the popping crease. Diagrams setting out the crease markings can be found in Appendix C.[37]  Law 8: The wickets. The wicket consists of three wooden stumps that are 28 inches (71.12 cm) tall. The stumps are placed along the bowling crease with equal distances between each stump. They are positioned so that the wicket is 9 inches (22.86 cm) wide. Two wooden bails are placed on top of the stumps. The bails must not project more than 0.5 inches (1.27 cm) above the stumps, and must, for men's cricket, be 4.31 inches (10.95 cm) long. There are also specified lengths for the barrel and spigots of the bail. There are different specifications for the wickets and bails for junior cricket. The umpires may dispense with the bails if conditions are unfit (i.e. it is windy so they might fall off by themselves). Further details on the specifications of the wickets are contained in Appendix D to the Laws.[38] Law 9: Preparation and maintenance of the playing area. When a cricket ball is bowled it almost always bounces on the pitch, and the behaviour of the ball is greatly influenced by the condition of the pitch. As a consequence, detailed rules on the management of the pitch are necessary. This Law contains the rules governing how pitches should be prepared, mown, rolled, and maintained.[39] Law 10: Covering the pitch. The pitch is said to be 'covered' when the groundsmen have placed covers on it to protect it against rain or dew. The Laws stipulate that the regulations on covering the pitch shall be agreed by both captains in advance. The decision concerning whether to cover the pitch greatly affects how the ball will react to the pitch surface, as a ball bounces differently on wet ground as compared to dry ground. The area beyond the pitch where a bowler runs so as to deliver the ball (the 'run-up') should ideally be kept dry so as to avoid injury through slipping and falling, and the Laws also require these to be covered wherever possible when there is wet weather.[40] Law 11: Intervals. There are intervals during each day's play, a ten-minute interval between innings, and lunch, tea and drinks intervals. The timing and length of the intervals must be agreed before the match begins. There are also provisions for moving the intervals and interval lengths in certain situations, most notably the provision that if nine wickets are down, the lunch and tea interval are delayed to the earlier of the fall of the next wicket and 30 minutes elapsing.[41] According to Law 11.8, a drinks interval "shall be kept as short as possible and in any case shall not exceed 5 minutes."[42] Law 12: Start of play; cessation of play. Play after an interval commences with the umpire's call of "Play", and ceases at the end of a session with a call of "Time". The last hour of a match must contain at least 20 overs, being extended in time so as to include 20 overs if necessary.[43] Innings and resultLaws 13 to 16 outline the structure of the game including how one team can beat the other. Law 13: Innings. Before the game, the teams agree whether it is to be one or two innings for each side, and whether either or both innings are to be limited by time or by overs. In practice, these decisions are likely to be laid down by Competition Regulations, rather than pre-game agreement. In two-innings games, the sides bat alternately unless the follow-on (Law 14) is enforced. An innings is closed once ten batsmen are dismissed, no further batsmen are fit to play, the innings is declared or forfeited by the batting captain, or any agreed time or overs limit has expired. The captain winning the toss of a coin decides whether to bat or to bowl first.[44] Law 14: The follow-on. In a two-innings match, if the side batting second scores substantially fewer runs than the side which batted first, then the side that batted first can require their opponents to bat again immediately. The side that enforced the follow-on has the chance to win without batting again. For a game of five or more days, the side batting first must be at least 200 runs ahead to enforce the follow-on; for a three- or four-day game, 150 runs; for a two-day game, 100 runs; for a one-day game, 75 runs. The length of the game is determined by the number of scheduled days play left when the game actually begins.[45] Law 15: Declaration and forfeiture. The batting captain can declare an innings closed at any time when the ball is dead, and may also forfeit an innings before it has started.[46] Law 16: The result. The side which scores the most runs wins the match. If both sides score the same number of runs, the match is tied. However, the match may run out of time before the innings have all been completed; in this case, the match is drawn.[47] Overs, scoring, dead ball and extrasThe Laws then move on to detail how runs can be scored. Law 17: The over. An over consists of six balls bowled, excluding wides and no-balls. Consecutive overs are delivered from opposite ends of the pitch. A bowler may not bowl two consecutive overs.[48] Law 18: Scoring runs. Runs are scored when the two batsmen run to each other's end of the pitch. Several runs can be scored from one ball.[49]  Law 19: Boundaries. A boundary is marked around the edge of the field of play. If the ball is hit into or past this boundary, four runs are scored, or six runs if the ball does not hit the ground before crossing the boundary.[50] Law 20: Dead ball. The ball comes into play when the bowler begins his run-up, and becomes dead when all the action from that ball is over. Once the ball is dead, no runs can be scored and no batsmen can be dismissed. The ball becomes dead for a number of reasons, most commonly when a batter is dismissed, when a boundary is hit, or when the ball has finally settled with the bowler or wicketkeeper.[51] Law 21: No ball. A ball can be a no-ball for several reasons: if the bowler bowls from the wrong place; if he straightens his elbow during the delivery; if the bowling is dangerous; if the ball bounces more than once or rolls along the ground before reaching the batter; or if the fielders are standing in illegal places. A no-ball adds one run to the batting team's score, in addition to any other runs which are scored off it, and the batter cannot be dismissed off a no-ball except by being run out, hitting the ball twice, or obstructing the field.[52] Law 22: Wide ball. An umpire calls a ball "wide" if, in his or her opinion, the ball is so wide of the batter and the wicket that he could not hit it with the bat playing a normal cricket shot. A wide adds one run to the batting team's score, in addition to any other runs which are scored off it, and the batter cannot be dismissed off a wide except by being run out or stumped, by hitting his wicket, or obstructing the field.[53] Law 23: Bye and leg bye. If a ball that is not a wide passes the striker and runs are scored, they are called byes. If a ball hits the striker but not the bat and runs are scored, they are called leg-byes. However, leg-byes cannot be scored if the striker is neither attempting a stroke nor trying to avoid being hit. Byes and leg-byes are credited to the team's but not the batter's total.[54] Players, substitutes and practiceLaw 24: Fielders' absence; Substitutes. In cricket, a substitute may be brought on for an injured fielder. However, a substitute may not bat, bowl or act as captain. The original player may return if he has recovered.[55] Law 25: Batter's innings; Runners A batter who becomes unable to run may have a runner, who completes the runs while the batter continues batting. (The use of runners is not permitted in international cricket under the current playing conditions.) Alternatively, a batter may retire hurt or ill, and may return later to resume his innings if he recovers.[56] Law 26: Practice on the field. There may be no batting or bowling practice on the pitch during the match. Practice is permitted on the outfield during the intervals and before the day's play starts and after the day's play has ended. Bowlers may only practice bowling and have trial run-ups if the umpires are of the view that it would waste no time and does not damage the ball or the pitch.[57] Law 27: The wicket-keeper. The keeper is a designated player from the bowling side allowed to stand behind the stumps of the batter. They are the only fielder allowed to wear gloves and external leg guards.[58] Law 28: The fielder. A fielder is any of the eleven cricketers from the bowling side. Fielders are positioned to field the ball, to stop runs and boundaries, and to get batsmen out by catching or running them out.[59] Appeals and dismissalsLaws 29 to 31 cover the main mechanics of how a batter may be dismissed.  Law 29: The wicket is down. Several methods of dismissal occur when the wicket is put down. This means that the wicket is hit by the ball, or the batter, or the hand in which a fielder is holding the ball, and at least one bail is removed; if both bails have already been previously removed, one stump must be removed from the ground.[60] Law 30: Batter out of his/her ground. The batsmen can be run out or stumped if they are out of their ground. A batter is in his ground if any part of him or his bat is on the ground behind the popping crease, and the other batter was not already in that ground. If both batters are in the middle of the pitch when a wicket is put down, the batter closer to that end is out.[61] Law 31: Appeals. If the fielders believe a batter is out, they may ask the umpire "How's That?" before the next ball is bowled. The umpire then decides whether the batter is out. Strictly speaking, the fielding side must appeal for all dismissals, including obvious ones such as bowled. However, a batter who is obviously out will normally leave the pitch without waiting for an appeal or a decision from the umpire.[62] Laws 32 to 40 discuss the various ways a batter may be dismissed. In addition to these 9 methods, a batter may retire out, which is covered in Law 25. Of these, caught is generally the most common, followed by bowled, leg before wicket, run out and stumped. The other forms of dismissal are very rare. Law 32: Bowled. A batter is out if his wicket is put down by a ball delivered by the bowler. It is irrelevant whether the ball has touched the bat, glove, or any part of the batter before going on to put down the wicket, though it may not touch another player or an umpire before doing so.[63] Law 33: Caught. If a ball hits the bat or the hand holding the bat and is then caught by the opposition within the field of play before the ball bounces, then the batter is out.[64] Law 34: Hit the ball twice. If a batter hits the ball twice, other than for the sole purpose of protecting his wicket or with the consent of the opposition, he is out.[65] Law 35: Hit wicket. If, after the bowler has entered his delivery stride and while the ball is in play, a batter puts his wicket down by his bat or his body he is out. The striker is also out hit wicket if he puts his wicket down by his bat or his body in setting off for a first run. "Body" includes the clothes and equipment of the batter .[66] Law 36: Leg Before Wicket (LBW). If the ball hits the batter without first hitting the bat, but would have hit the wicket if the batter was not there, and the ball does not pitch on the leg side of the wicket, the batter will be out. However, if the ball strikes the batter outside the line of the off-stump, and the batter was attempting to play a stroke, he is not out.[25] Law 37: Obstructing the field. If a batter willfully obstructs the opposition by word or action or strikes the ball with a hand not holding the bat, he is out. If the actions of the non-striker prevent a catch taking place, then the striker is out. Handled the Ball was previously a method of dismissal in its own right.[67] Law 38: Run out. A batter is out if at any time while the ball is in play no part of his bat or person is grounded behind the popping crease and his wicket is fairly put down by the opposing side.[68] Law 39: Stumped. A batter is out when the wicket-keeper (see Law 27) puts down the wicket, while the batter is out of his crease and not attempting a run.[69] Law 40: Timed out. An incoming batter must be ready to face a ball (or be at the crease with his partner ready to face a ball) within 3 minutes of the outgoing batter being dismissed, otherwise the incoming batter will be out.[70] Unfair playLaw 41: Unfair play. There are a number of restrictions to ensure fair play covering: changing the condition of the ball; distracting the batsmen; dangerous bowling; time-wasting; damaging the pitch. Some of these offences incur penalty runs, others can see warnings and then restrictions on the players.[71] Law 42: Players' conduct. The umpires shall penalise unacceptable conduct based on the severity of the actions. Serious misconduct can see a player sent from field; lesser offences, a warning and penalty runs.[72] AppendicesAppendix A: Definitions. A set of definitions / clarifications of phrases not otherwise defined within the Laws.[73] Appendix B: The bat (Law 5). Specifications on the size and composition of the bat use in the game.[74] Appendix C: The pitch (Law 6) and creases (Law 7). Measurements and diagrams explaining how the pitch is marked out.[75] Appendix D: The wickets (Law 8). Measurements and diagrams explaining the size and shape of the wickets.[76] Appendix E: Wicket-keeping gloves. Restrictions on the size and design of the gloves worn by the wicket-keeper.[77] References

Bibliography

|