|

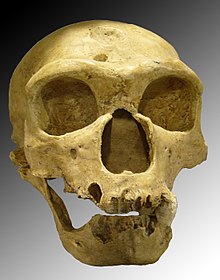

La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1

La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 ("The Old Man") is an almost-complete male Neanderthal skeleton discovered in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France by A. and J. Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon in 1908. The individual was about 40 years of age at the time of his death. He was in bad health, having lost most of his teeth and suffering from bone resorption in the mandible and advanced arthritis. It is the most convincing example of a possible Neanderthal deliberate burial,[1] but like all claimed Neanderthal burials, it is considered controversial.[2]  The remains were first studied by Marcellin Boule, whose reconstruction of Neanderthal anatomy based on la Chapelle-aux-Saints material shaped popular perceptions of the Neanderthals for over thirty years. The La Chapelle-aux-Saints specimen is typical of "classic" Western European Neanderthal anatomy. It is estimated to be about 60,000 years old. Boule's reconstruction of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1, published during 1911–1913, depicted Neanderthals with a thrust-forward skull, a spine without curvature, bent hips and knees and a divergent big toe.[3] This depiction fitted in well with contemporary evolutionary scenarios in which Neanderthals were not considered to be direct ancestors of modern humans (the relationship of Neanderthals to modern humans remains a major debate in anthropology today).[4] In 1957, the remains were re-examined by Straus and Cave. These researchers depicted Neanderthal anatomy as being much more modern; in particular, their posture and gait was more or less identical to that of modern humans. Straus and Cave attributed Boule's errors to the severe osteoarthritis in the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal, although physical anthropologist Erik Trinkaus has suggested that Boule's errors were primarily related to the fragmentary nature of the remains.[4] This specimen had lost many of his teeth, with evidence of healing. All of the mandibular molars were absent and consequently, some researchers suggested that the 'Old Man' would have needed someone to process his food for him. This was widely cited as an example of Neanderthal altruism, similar to Shanidar 1. Later studies have shown that La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 did have a number of incisors, canines and premolars in place and therefore would have been able to chew his own food, although perhaps with some difficulty.[5] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||