|

Kražiai massacre

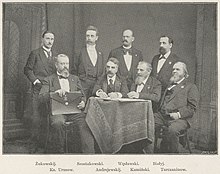

Kražiai massacre (Lithuanian: Kražių skerdynės) was an attack by a Russian Don Cossack regiment on Lithuanians protesting the planned closure of a Roman Catholic church in Kražiai, then part of the Russian Empire, on 22 November 1893. As part of wider Russification efforts, the Tsarist government decided to close the women's Benedictine monastery in Kražiai. The locals petitioned to keep the monastery's Church of the Immaculate Conception open and transform it into a parish church. The Tsar ordered the monastery closed and demolished in June 1893. The locals started a constant vigil inside the church, protecting it from members of the clergy who tried to comply with the orders. On 21 November, Governor of Kaunas Nikolay Klingenberg personally arrived to the town to supervise the closure. Lithuanians resisted and overpowered 70 policemen that Klingenberg brought with him. The next morning, about 300 Don Cossacks arrived from Varniai and were given a free rein to loot and brutalize. According to official data, nine people died and 54 were injured.[1] At least 24 women were raped and 16 men flogged with nagaikas. 71 persons were put on trial for rioting and disobeying police orders, but the cruelty of the Cossacks caused a public outcry and the people received a pardon from the Tsar. The event became a rallying cry of the Lithuanian National Revival.[2] Background After the Third Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, Lithuania became part of the Russian Empire. In response to the failed uprisings in 1831 and 1863–1864, Tsarist authorities enacted various Russification policies, including the Lithuanian press ban and various restrictions on the Roman Catholic Church. The government often closed churches and chapels attached to manors or cemeteries as well as monasteries and their churches.[3] In Samogitia, authorities closed some 46 Catholic monasteries, and 22 churches and chaples.[4] In five towns (Dūkštas, Šešuoliai, Tytuvėnai, Kęstaičiai, and Kražiai) local residents attempted to protest and resist the closures.[3] The monastery and church in Kęstaičiai were guarded by locals, but closed using a Cossack unit and demolished in 1887.[5] According to the memoirs of Kražiai survivors, they had received tips from people involved in defending the Kęstaičiai monastery.[1] Kražiai was a small town with 1,761 residents according to the Russian Empire Census in 1897.[6] The Benedictine women's monastery in Kražiai dated since 1639. In 1757–1763, the monastery constructed the brick church of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary (architect Thomas Zebrowski).[1] The church was considered the "nobles' church," meaning it was the most frequently attended by the local nobility.[7] The nuns also mostly came from noble backgrounds and spoke Polish in their daily lives. The liturgy was conducted in Polish and Latin, the gospel was read in Polish and Samogitian, while the sermons were delivered exclusively in Samogitian.[8] The nuns communicated with the local population in Samogitian and were respected and liked by them.[8] On 12 December 1891, Tsar Alexander III of Russia ordered the monastery closed and nine remaining nuns transferred to a Benedictine monastery in Kaunas. Town residents sent the first petitions to the Tsar, Governor-General of Vilna, and Bishop of Samogitia on 7 February 1892.[9] They sent many other petitions, including a total of eight petitions to the Tsar himself, asking to convert the monastery church into a parish church and transform the crumbling wooden parish Church of the Archangel Michael into a cemetery chapel.[10] Governor-General Ivan Kakhanov investigated the issue and recommended to the Ministry of the Interior of the Russian Empire to transfer the churches. However, on 1 January 1893, Kakhanov who was implicated in a corruption scandal (accused of misappropriating funds collected for a monument to Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky) was replaced by Pyotr Orzhevsky, former commander of the Special Corps of Gendarmes.[9] Orzhevsky was a strong supporter of the various Russification policies and perhaps hoped that his strict stance would gain him favor in Saint Petersburg and restart his political career.[9] The Tsar ordered the monastery and church closed and demolished on 22 June 1893; the stones and bricks were to be used to construct an agricultural school.[11] The Benedictine nuns attempted to delay their move to Kaunas using various excuses, including lack of warm clothing and ill health. Due to poor health, Aleksandra Sieliniewska, Benedykta Choromańska, Salomea Siemaszkówna, and Abbess Michalina Paniewska remained in Kražiai.[12] They were visited by Russian policemen from Raseiniai and two doctors to inspect their health. When the nuns would not allow the men into their monastery, they broke down the doors and forcibly removed the nuns escorting them to Kaunas.[9] The nuns were forcibly removed on 25 October 1892 and 4 May 1893.[3] This galvanized town residents who started a constant vigil inside the church to protect it and its valuables on 13 September 1893.[10] Several times, local priests attempted to remove the Eucharist, but were stopped by the locals.[11] The residents sent letters not only to the central Russian authorities but also to the governments of foreign countries: Austria-Hungary, Germany, Italy, France, the United Kingdom, USA, and Denmark.[13] The local nobility assisted in drafting these letters. Activists of the Lithuanian national revival, particularly those associated with the journal Žemaičių ir Lietuvos apžvalga, which had been published since 1890 in Tilsit, also became involved in the defense of the church.[14] MassacreGovernor of Kaunas Nikolay Klingenberg personally arrived to the town in the late evening of 21 November. He was met by Lithuanians holding up two large portraits of Tsar Alexander III of Russia and his wife Maria Feodorovna to showcase their loyalty to the Tsar and pleading him to wait for the Tsar to respond to their latest petition.[9] Klingenberg brought about 70 policemen and ordered them to remove the residents (about 300–400 people) from the church. Lithuanians resisted and overpowered the police. Chief of the Raseiniai Uyezd was beaten and almost hanged, but freed by the Russian policemen, while Klingenberg barricaded himself in a church choir balcony.[9] The scuffle continued through the night. Lithuanians attempted to negotiate with Klingenberg and force him to write a protocol admitting his wrongdoings.[9] As prearranged, about 300 Cossacks from the 3rd Don Cossack Regiment arrived to the town early next morning. They easily overpowered Lithuanians armed with sticks, flails, and stones. The Cossacks aimed their blows to the head and face as those wounds would be easily spotted later and would help searching for those who managed to escape.[15] The Cossacks freed Klingenberg who ordered the town surrounded and every Catholic, regardless of age or sex, arrested. The arrested men were flogged with nagaikas. Lithuanian sources published 16 names of flogged men, but claimed that they numbered 69.[9] Using the excuse of searching for escaped church defenders, the Cossacks were allowed to plunder the town and surrounding villages for two weeks.[15] They raped women – a source from 1933 counted 24 women, including two pregnant women and a 12-year old gang raped by eight Cossacks. Dozens were injured. Nine people died due to beatings and other injuries.[9] There were rumors of people drowning in the nearby Kražantė river.[6] The Cossacks confiscated 225 sticks and flails.[11] The deceased were buried immediately, thrown into a pit meant for slaking lime at the local cemetery. The priests were forbidden from recording the names of the victims and performing funeral rites, including sprinkling the ground with holy water.[16] Aftermath  In total, 330 people were interrogated and 71 (34 peasants, 27 nobles, and 10 city residents; 55 men and 16 women)[2] were arrested and put on trial in Vilnius.[10] They were defended pro bono by eight attorneys, Russians Sergey Andreyevsky, Konstantin Bialy, Alexander Turchaninov, Alexander Urusov, Vladimir Zhukovsky and Poles Jan Maurycy Kamiński, Leon Dunin-Szostakowski, and Michał Węsławski. Michał Węsławski along with Stanislovas Raila, served as an interpreter for peasants who spoke only Samogitian and did not know Russian.[17] The trial was held on 20–29 September 1894 in Vilnius. Following the letter of the law, 36 people were acquitted while 35 people were found guilty and received various sentences, including four men who received 10 years of katorga. However, the judges themselves petitioned the new Tsar Nicholas II of Russia to pardon the people and commute the 10-year katorga to one year in prison.[9] A collection of court documents was published in Polish in 1895.[3] The church interior was almost fully demolished.[11] Sculptures were smashed, paintings had bullet holes. Priests moved two side altars to the church in Maironiai and some other items to the parish church in Kražiai, but many other items were looted. The church was left essentially empty and was closed, but not demolished. It was returned to the parish in 1908 and, after extensive repairs, reopened on 4 September 1910.[11] Other monastery buildings, except for the chapel of St. Roch, did not survive.[1] The wooden Church of the Archangel Michael burned down in June 1941.[18] News of the event quickly spread across Lithuania and reached international press, including New York World News and Kölnische Volkszeitung.[3] Lithuanian press, including Varpas, Ūkininkas, and Vienybė lietuvninkų, devoted significant attention to the events. They exaggerated casualties and claimed, for example, that 300 Lithuanians were killed or that 600 women were raped.[3] The press attacked the popular notion of "good Tsar, bad bureaucrats" and praised Kražiai defenders as martyrs and an inspirational example for others to follow. The Lithuanian press also covered the trial, publishing defense attorney speeches and special prayers for the defendants. Soon separate booklets were published in East Prussia (where Lithuanian publishing concentrated) and United States, including a play by Juozapas Žebrys. The events caused a stir among Lithuanian Americans who collected donations, held lectures, and organized protest rallies.[3] The largest rallies were held on 28 January 1894 in Chicago (estimated 6,000 people) and on 4 March 1894 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania (estimated 7,000 Lithuanians and 3,000 of other nationalities).[3][19] Cultural impact Historian Nerijus Udrėnas summarized that the events in Kražiai accelerated two major trends of the Lithuanian National Revival – separation of the dual Polish-Lithuanian identity into just Polish or Lithuanian national identities and separation of the Lithuanian National Revival into two main branches (conservative Catholic and liberal secular).[3] Polish press also covered the events, often claiming that the defenders were Poles organized and led by Polish szlachta. Polish journalist Zenon Parvi wrote a play about the events. Lithuanians protested such attempts to usurp and appropriate the events in the spirit of the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and in support of the dual Polish-Lithuanian identity. Lithuanian press denied any involvement of Poles while Polish press blamed Lithuanians for fracturing the united front against the Tsarist regime.[3] In March 1894, Pope Leo XIII issued encyclical Caritatis on the church in Poland sparking a fierce debate between Catholic and secular Lithuanian activists. Vincas Kudirka in Varpas attacked the encyclical because the pope urged compliance and obedience to the Tsarist regime and thus "betrayed the blood spilled in Kražiai".[20] Defenders of the encyclical, including Pranciškus Bučys, pointed out that it forced Tsarist authorities to make concessions and relax restrictions on the Catholic Church and that the pope urged obedience only as much as it did not go against religious beliefs and freedom.[10] After the debate, most of the clergy withdrew their support to Varpas and instead focused on Catholic Žemaičių ir Lietuvos apžvalga and Tėvynės sargas.[21]  The official Catholic hierarchy did not promote the memory of the event because the clergy was very passive if not supportive of the Tsarist authorities.[3] The event was remembered in 1933, the 40th anniversary of the massacre. At the time, the authoritarian regime of Antanas Smetona attempted to lessen the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and thus weaken its main opponent, the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party. Therefore, the struggle against government oppression for religious freedom was once again relevant.[3] According to contemporary press reports, some 10,000 people attended the anniversary events in Kražiai, organized by the Union for the Liberation of Vilnius. The union encouraged people to follow the example of Kražiai defenders and continue to fight for the Vilnius Region disputed with the Second Polish Republic. 38 of the surviving defenders were awarded the Order of Vytautas the Great. Other events were held in other cities and towns, organized by other Lithuanian organizations. Schools were ordered to devote one lesson on 22 November to discussing the massacre.[3] Film director Juozas Vaičkus wanted to produce an epic film on the massacre, one of the first films in Lithuanian, and visited 136 cities and towns raising money. The film was not produced due to financial difficulties (it received no support from the government) and Vaičkus' death in 1935.[3] In 1934, exhibition about Kražiai and religious repressions in Russian Empire in general was shown in Kaunas, Šiauliai, Klaipėda, and Panevėžys. A small memorial museum in Kražiai was opened in summer 1938.[3] The same year, writer Jonas Marcinkevičius published a two-volume historical novel about the events. There were other plans for commemorating the events with special medals, monument, or enlarged museum all aimed at the anticipated grand ceremony in 1943, the 50th anniversary. However, any such plans were interrupted by World War II and the Soviet occupation in June 1940.[3] References

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||||