|

Killing of Nick Berg

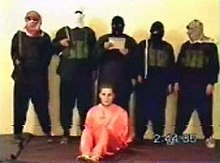

Nicholas Evan Berg (April 2, 1978 – May 7, 2004) was an American freelance radio-tower repairman[1] who went to Iraq after the United States' invasion of Iraq. He was abducted and beheaded according to a video released in May 2004 by Islamist militants in response to the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse involving the United States Army and Iraqi prisoners. The CIA claimed Berg was murdered by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.[2] The decapitation video was released on the internet, reportedly from London to a Malaysian-hosted homepage by the Islamist organization Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad.[3] Early life and educationBerg was born in Charlotte, North Carolina and grew up in West Whiteland Township, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia.[4] He was referred to as a "religious Jew."[4] Berg graduated from Henderson High School in West Chester in 1996.[5][6] In 1996, he was a student at Cornell University[7] but later dropped out.[8] He took classes at Drexel University in 1998,[9] and, in 1999, attended summer sessions on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania.[7] At some point, Berg took a class at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.[10] He never earned a college degree.[7] In 2002, with family members, Berg created Prometheus Methods Tower Service.[8] He inspected and rebuilt communication antennas, and had previously visited Kenya and Uganda on similar projects. Berg set up a subsidiary of his company, Prometheus Tower Services, Inc., in Kenya.[11][when?] Travels and detentionBerg first arrived in Iraq on December 21, 2003, and made arrangements to secure contract work for his company. He also went to the northern city of Mosul, visiting an Iraqi man whose brother had been married to Berg's late aunt. Leaving on February 1, 2004, he returned to Iraq on March 14, 2004, only to find that the work he was promised was unavailable.[citation needed] Throughout his time in Iraq, he maintained frequent contact with his family in the United States by telephone and email.[citation needed] Berg had intended to return to the United States on March 30, 2004, but he was detained in Mosul on March 24.[12] His family claims that he was turned over to U.S. officials and held for 13 days[13][14] without access to legal counsel. FBI agents visited his parents to confirm his identity on March 31, 2004, but he was not immediately released.[citation needed] After his parents filed suit in federal court in Philadelphia on April 5, 2004, claiming that he was being held illegally, he was released from custody. He said that he had not been mistreated during his confinement. The U.S. maintains that at no time was Berg in coalition custody, but rather that he was held by Iraqi forces. The Mosul police deny they ever arrested Berg, and Berg's family has turned over an email from the U.S. consul stating "I have confirmed that your son, Nick, is being detained by the U.S. military in Mosul."[15] According to the Associated Press, Berg was released from custody on April 6, 2004 and advised by U.S. officials to take a flight out of Iraq, with their assistance. Berg is said to have refused this offer and traveled to Baghdad, where he stayed at the Al-Fanar Hotel. His family last heard from him on April 9, 2004. Berg had his last contact with U.S. officials on April 10, 2004 and did not return again to his hotel after that date. He was interviewed for filmmaker Michael Moore's film Fahrenheit 9/11.[16] Moore chose not to use the footage of his interview with Berg, but instead shared it with Berg's family following his death. DisappearanceBerg's family became concerned after not hearing from him for several days. Although a U.S. State Department investigator looked into Berg's disappearance, official government inquiries produced no leads. His family, frustrated with what they say was a lack of action by the U.S. government, also hired a private investigator and contacted both their Congressional delegation and the Red Cross in search of information.[citation needed] According to The Guardian it is unclear how Berg came to be kidnapped.[17] Death Berg's body was found decapitated on May 8, 2004, on a Baghdad overpass by a U.S. military patrol. Berg's family was informed of his death two days later. Military sources stated publicly at the time that Berg's body showed "signs of trauma", but did not disclose that he had been decapitated. On May 11, 2004, the website of the militant jihadist forum Muntada al-Ansar[18] posted a video with the opening title of "Abu Musab al-Zarqawi slaughters an American", which shows Berg being decapitated. The video is about five and a half minutes long. The video shows Nick Berg, seated, facing the camera and his captors standing behind him also facing the camera.[19] Berg is wearing an orange jumpsuit, similar to ones worn by prisoners in U.S. custody.[20] His captors are all masked, their identities concealed.[20] He identifies himself: "My name is Nick Berg, my father's name is Michael, my mother's name is Suzanne. I have a brother and sister, David and Sarah. I live in West Chester, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia." A lengthy statement is read aloud by a masked man. The masked men then converge on Berg. Two of them hold him down, while one decapitates him with a knife. PerpetratorsThe video title claims the decapitator was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi,[21] but this can not be determined as all the men are masked.[20] Berg screams as the masked men shout "Allahu Akbar". After the head is severed, one of the men displays the head to the camera, then lays it down on the decapitated body. During the video, the masked man reading the statement said the killing was in revenge for the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse. The man says Muslims should seek vengeance for Abu Ghraib, and that the Muslim clergy had been complacent.[22][20] The man also threatens further deaths, and makes specific threats to U.S. President George W. Bush and Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf.[17] Media in the United States and around the world grappled with the question of how much graphics to print. The Dallas Morning News showed an image in which the killer holds Berg's severed head, while Seattle Times only displayed the image of the killer. British newspaper The Independent urged restraint, arguing the video was propaganda and publishing images from it "plays into the hands" of terrorists.[23] ReactionsBerg's killing was condemned by the Arab League, and United Nations, as well as Saudi Arabia, Jordan and UAE.[24][25] Many others in the Muslim world also condemned the killing,[26][27] and BBC journalist Paul Wood found that the "Arab street" condemned the killing of Berg, saw it as contrary to Islam, and saw it as a reaction to US prison abuses.[28] Encounter with Zacarias MoussaouiOn May 14, 2004, it was revealed that Nick Berg had come up during the U.S. government's investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui, a 9/11 conspirator. Berg's email address had been used by Moussaoui prior to the September 11, 2001 attacks. According to Berg's father, Nick Berg had a chance encounter with an acquaintance of Moussaoui on a bus in Norman, Oklahoma. This person had asked to borrow Berg's laptop computer to send an email. Berg gave the details of his own email account and password, which were later used by Moussaoui. The FBI found that Berg had no direct terrorism connections or direct link with Moussaoui.[29] Arrests and confessionsOn May 14, 2004, citing "Iraq sources", Sky News reported that four people had been arrested for the murder.[citation needed] Two were later released.[30] Alternatively, on July 5, 2004, Sky News reported that four men were arrested in connection with the Nick Berg decapitation.[31] Suspects arrested for Berg's killing were former members of Fedayeen Saddam paramilitary group.[32] On August 5, 2004, Le Nouvel Observateur published a feature story by Sara Daniel[33] detailing her meeting with Abu Rashid, a leader of the Mujahideen Council in Fallujah. He claims that he killed Nick Berg, Kim Sun-il and Iraqis who collaborated with US forces. He also states that they attempted a prisoner exchange with Berg but were rebuffed by American officials. See also

References

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||