|

Journalism of early modern Europe

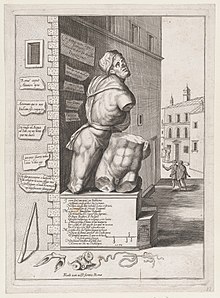

In the early modern period of Europe (1500–1700), journalism originally consisted of handwritten newsletters used to convey political, military, and economic news quickly and efficiently throughout the continent. They were often written anonymously and delivered through a complex system of couriers. They are divided into the Italian avvisi (Italian: [avˈviːzi]; singular: avviso) and the German contemporary equivalent Zeitungen (literally: newspapers).[1] From 1605 in Germany, and in the next decades in other European countries, the newsletters started to be printed as well. Because handwritten material was less subject to censorship and quicker to be produced,[2] handwritten newsletters continued to be produced in parallel with printed newspapers for all the 17th century, and sporadically also in the 18th century.[a] OriginThe avvisi found their origins, and peaked, in the early modern Italian world in Rome and Venice. In the Middle Ages, diplomats, merchants, and scholars would gather information and keep records about news that were relevant to them through journals, account books, and letters. The latter of these became part of a complex network of correspondence, such as that compiled in the Fuggerzeitungen, the Medici court's epistolary archive, and the Urbinate collection in the Vatican Library.[1][3][4] Over time, this information that had been provided for free eventually was sold by specialists and distributed by couriers in order to meet the high demand for such a product.[3] Multiple factors in 16th century Venice gave rise to the print culture in which the Avvisi originated. These were the growing local publishing industry, an Italian culture that encouraged the recording of private and public events, the relatively high literacy and education of the aristocracy that produced and consumed print, and the participation in European political and commercial correspondence networks by Venetians as a necessity of trade.[3] In fact, Venice's print industry was so large that its 150 presses by the end of the 16th century more than double its closest rival (Paris), and accounted for between one seventh and one eighth of the European output in that period.[3] However, the Italians' production of news would eventually fall behind in output and readership to German news writers.[1] Germany and the Spanish Netherlands followed a similar process to Italy later on in the century, with Antwerp and Cologne emerging as significant producers of news sheets, in their case called Zeitungen.[1] These reports originated more significantly from commercial sources than their Italian predecessors. German zeitungen reached the peak of (preserved) production in the 1590s, with an almost six-fold increase in the number of zeitungen in the information distribution records of the Fugger banking family (Fuggerzeitungen) between 1578 and 1595.[1] Content The content and character of the avvisi differed between cities, especially between Rome and Venice. Roman avvisi contained ecclesiastical, political, and criminal intrigue, taking advantage of opposing factions willing to divulge state secrets or official gossip for their own benefit. These were then read by church and government officials as well as the nobility. Such was the partisan (and sometimes scandalous) comments on public affairs that they became censored by the Pope and several copyists were imprisoned or executed. Venetian avvisi, however, were more conservative in their coverage of such events and more preoccupied with commercial matters. This is not to say that there was no public criticism of public figures in Venice, but rather they often took other forms such as in satire performed during the carnival of Venice and other such festivals as well as pasquinades.[3] Both cities' avvisi became more diversified over time, eventually anticipating modern newspapers.[3] Italian states originally sourced individual news pieces from German regions in Italian, but over time they began receiving them as part of complete translations of zeitungen. As a consequence, news from Central and Western Europe began to spread throughout Italy in almost identical versions due to the consolidation of news sources, and vice versa through a similar process.[1] The German zeitungen were also somewhat different in content to the avvisi, usually a third shorter and would mention much fewer people. In addition, zeitungen would usually report four or five items, whereas the number of items and detail in avvisi would vary based on proximity to the events. Zeitungen would also cover military aspects of conflicts in more detail than the politically and legally-inclined avvisi.[1] ImportanceGovernment and church officials realized the powerful tools of communication the avvisi represented and Venice began publishing its own (named foglie di notizie, or news sheets) sometime around 1563. These were published on Sundays under the authority of the Venetian government and while originally intended for its ambassadors abroad, they were often read aloud in public spaces of Venice.[3] Governments would also have public servants hired in charge of compiling and collecting avvisi from abroad.[4] Interfering with the delivery of avvisi to other realms quickly became a political tool that paralyzed government functionaries, while the sharing of rare avvisi was used to strengthen alliances.[4] The news sheets became highly useful in warfare, such as in the management of logistics or predicting the progress of conflict. Such was their importance that while preparing to lay siege to Calais, a Tuscan commander wrote to a court official stationed in Brussels "I remind you again about the attachments [of avvisi] and I await the gazettes and will accept no excuse."[4] Avvisi were highly influential in the public opinion of events and different agents would attempt to limit or increase their availability depending on their agenda. After the Great Armada was destroyed, the Spanish Minister of War both suppressed reports of the heavy defeat as well as commissioning false positive reports — an early version of propaganda.[4] Therefore, the constant arrival of fresh avvisi was needed to dispel false rumors or observations of older ones, such as warnings of enemy sieges that did not happen.[4] In response to unreliable reports, methods to compare and verify news were developed, such as overlapping coverage by sources and the consultation of many merchants when information was vague.[4] German translations of avvisi show attempts by translators to reduce the amount of subjective analysis in their sources through such methods.[1] False avvisi were still useful, however, to understand propaganda campaigns by other states, possible trends in public opinion, or international reception of one's own government and so were still analyzed.[4] For example, Roman coverage of the Papal reception of Protestant German princes in 1601 mentions this was done "to put them in the mood for a good conversion", while German coverage says the action should be understood as a sign of respect to the power of one of the princes.[1] The differences between these reports shows the differences in both the religious and political opinion of the two regions. Avvisi were helpful to preventing epidemics, as whenever they raised suspicion of plague in other cities nearby Italian cities were able to institute control measures in response. These were often draconian, such as in the case of a Milanese courier that was shot to death in 1575 by order of Florentine ruler Francesco I de' Medici after being suspected of carrying the disease.[4] Intercity traffic would be blocked as a quarantine measure, and therefore the lack of or late arrival of news from a certain city or area allowed governments to plan responses in advance.[4]  DistributionDistribution of the avvisi began with the sources of information, often anonymous.[1] Reporters had networks of contacts filtering information from legislative bodies such as the Venetian senates or the Papal consistory; chancelleries; churches; foreign embassies; important households; and less formal environments such as shops, town squares, and market places.[1][5] Information was gathered and put together individually or at a scrittoria (writer's workshop). This process was originally done by hand, with printed avvisi not appearing in Venice until late in the 17th century.[3] Possible reasons for this were easier avoidance of censorship in hand-written form, reluctance of copyists to use printing technology (which they viewed as a threat to their job security), and clients desiring the status offered by hand-written information as opposed to the "vulgar" print.[3] Printed zeitungen, meanwhile, were available both earlier and with wider readership to their Italian counterparts.[1] The avvisi would then be distributed by regular news services and organized courier networks. Whether newsletters were sent weekly, bi-weekly, or annually depended on the type of news and the writer.[6] Payment for them also varied in form, initially only being offered per-unit and in secret, but eventually evolving into the possibility of regular, standardized subscriptions.[4] The range of information presented within avvisi was very broad, including countries within Europe but also developments in the New World and the East Indies.[4][5] The Mediceo del Principato, the archive of Medici court letters, includes creations from London and Constantinople in its over 100 volumes of avvisi, while the Fuggerzeitungen contains sheets originating in 88 different places.[4] The networks of individuals that compiled and traded in avvisi could be similarly diverse. One such example is Ulisse del Pace who was active in Trento and collected, transcribed, or forwarded news from Venice, Trento, Perugia, Milan, Rome and Turin within Italy and also Antwerp, Cologne, Prague, Lyon and Istanbul elsewhere.[1] Such was the wide distribution of avvisi in Italy compared to the other areas in Europe that when Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany was sent one by his representative in Valladolid to share with Francisco Gómez de Sandoval, 1st Duke of Lerma, he remarked that the newsletter was "of some importance, being so rare both the news from your parts, and the insights into such affairs”.[4] CensorshipEarly attempts at censorship were made by both Pope Pius V and the Council of Ten in the late 1500s, which both limited production of hand-written avvisi and forbade "disclosure of information".[4] The disclosure of state secrets to other rulers carried the death penalty. After the execution of a newswriter in November 1587 in Rome, the Pope explicitly forbade the spread outside of Rome of news regarding the Curia, while Venice used a similar law to execute another newswriter earlier in the year for sharing news to the duke of Ferrara.[1] After this newswriters and couriers were much more careful in their trade, but still continued producing and selling avvisi.[1] A popular Venetian reporter, Paolo Sarpi, was a minority in his time for holding the belief that the spread of information could not be stopped so censorship was a waste of resources. Sarpi believed that the only way to combat the enemy's newsletters is for the government to have its own avviso.[7] LegacyAvvisi and zeitungen remain an important aspect of European society in the transitionary period during the introduction of the printing press. The regular publishing schedule and public reading of these news sheets display a complex and active intellectual and cultural life in European courts and major cities through which the novel printing technology could rapidly spread and be adopted.[3] Furthermore, they show that modern newspapers were not a sudden introduction in society but rather an evolved form of previous ways of reporting information of interest.[3] Avvisi were also an important contributor in the creation of Grand Duchy of Tuscany's early postal service under the Medici, as the court put a heavy interest in acquiring the political intrigue they contained.[4] See alsoReferences

Notes

Works cited

External links

|