|

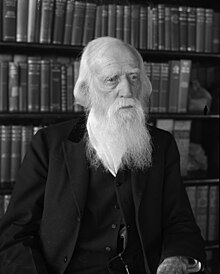

Joseph Widney

Joseph Pomeroy Widney, M.D. D.D. LL.D (December 26, 1841 – July 4, 1938), was an American doctor, educator, historian, and religious leader. After the American Civil War led him to medicine, he followed his brothers to California where he received his medical degree. He saw southern California as a "Garden of Eden". In Los Angeles he was a founder of the Los Angeles Medical Society. He was a strong proponent of the new University of Southern California, and became its second president and the founding dean of its school of medicine. The Los Angeles Public Library was one of his major interests. His real estate interests in California flourished, and he was an early environmentalist as well as promoter of the new metropolis. He believed deeply in Los Angeles becoming a major city with a seaport. The city would use water from across local mountains, and would recreate Lake Cahuilla. He was a founder of the Church of the Nazarene in Los Angeles, as well as a Methodist pastor. He published many books, mainly on his views about California and its history, but only Race Life of the Aryan Peoples was commercially published. He died at 96, having seen Los Angeles become a major city and seaport. One of the "most conspicuous Southern Californians of his generation",[1] Widney was a cultural leader in Los Angeles for nearly seventy years.[2] Early lifeJoseph Pomeroy Widney was born December 26, 1841, in Piqua, Ohio. The third son of John Wilson Widney and Arabella Maclay Widney, Widney was a nephew of Robert Samuel Maclay, and Charles Maclay. His father died of pneumonia at the age of 42, when Widney was 15.[3] After graduating from Piqua High School, he entered Miami University at Oxford, Ohio where, for five months, he studied Latin, Greek, and the classics. In 1907, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degree for his Race Life of the Aryan Peoples. In 1861 he enlisted in the Union Army in the Civil War (Ohio Volunteers). He served as a medical corpsman on ships on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. He was discharged in 1862 due to physical and nervous collapse.[4] With the encouragement of his two older brothers and his uncle, Charles Maclay, in California, Widney sailed to San Francisco via Panama, arriving in November 1862. He travelled throughout California, visited missions and lived with the Spanish-speaking inhabitants. He returned to university in 1865, receiving a Master of Arts degree from the California Wesleyan College (later the University of the Pacific). In January 1866, he moved to San Francisco. On June 4, 1866, he began the third session of the medical course at the Toland Medical College (later part of the University of California, San Francisco), graduating at the head of his class with a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree on October 2, 1866. Widney married twice. His first wife was Ida DeGraw Tuthill Widney on May 17, 1869, in San Jose, California. They lived in the Bunker Hill area, next to his brother Judge Robert M. Widney. Ida died in Los Angeles on February 10, 1879, and is buried in the Los Angeles City Cemetery.[5] His second wife was Mary Bray, whom he married on December 27, 1882, in Santa Clara, California. On February 18, 1884, a Los Angeles River flood caused the loss of 43 homes, including his own.[6] Dr. and Mrs. Widney moved to 150 W. Adams Boulevard (formerly S. 26th Street), nearer the new University of Southern California. As founder of the Flower Festival Society, she organized flower festivals to raise money for the Woman's Home, a home for poor working women.[7][8] Mary Bray Widney died on March 10, 1903, at their home at 150 W. Adams Boulevard, Los Angeles. Widney never remarried. Medical careerHe graduated from Toland Medical College, then the only one in California, on October 2, 1866. He re-enlisted in the army as a military surgeon. He was posted to Drum Barracks[9] in Wilmington, California, for a month in 1867, and was named Acting Assistant Surgeon for the Arizona Territory during the Apache Wars.[10] In 1868, he was discharged and moved to Los Angeles. He began his medical practice on October 8, 1868, sharing offices with John Strother Griffin (1816–1898). General William Tecumseh Sherman and Mexican bandido Tiburcio Vasquez were among his patients.[11] Before the "Anti-Quackery Law" was enacted in 1876, doctors were not licensed. Medical practitioners would advertise their medical skills.[12] On January 31, 1871, Widney helped found the Los Angeles County Medical Association, the oldest such association in California.[13] The founders wanted to establish medical schools and publications, and raise medical standards[14] Widney advocated aid to "the sickly poor" as a facet of public health and civic philanthropy.[14] From 1876 to 1901, medical licensing was done by the State Medical Society. In 1901, the State Board of Medical Examiners was created. Widney was one of the first licensed by the medical society. He became its president in 1877.[15] On May 12, 1937, a bust of Widney commissioned by the Los Angeles County Medical Association was placed in the lobby of their headquarters.[16] He believed in scientific medicine, and opposed faith healing or "mind cure" practitioners. In 1886, Widney, then professor of the principles and practice of medicine in the college of medicine of the University of Southern California, proposed a structure for the study of medicine. He advocated the creation of the Los Angeles and California Boards of Health, and was Los Angeles' first public health officer. In 1884, he helped re-organize the Southern California Medical Society. In 1886, he helped establish the Southern California Practitioner, the society's monthly journal, and served as an editor for the first few years.[17] AuthorIn 1872, he helped found the Los Angeles Library Association,[18] and served on its board of governors for the next six years. With Jonathan T. Warner and Judge Benjamin Hayes, Widney wrote and edited the first history of Los Angeles County,[19] the Centennial History of Los Angeles, published in 1876. In 1888, he collaborated with Walter Lindley (1852–1922), founder of the California Hospital Medical Center, in producing California of the South, one of the first California tourist guides. Other than his two-volume magnum opus, Race Life of the Aryan Peoples, published in 1907 by Funk and Wagnall,[20] he published his own works.[21] Widney said in Civilizations and Their Diseases (1937),

While at Drum Barracks and in Arizona, Widney became interested in climatology and conservation. He was chairman of the Los Angeles Meteorological committee for several years. Widney credited white settlement with improvements in the Southern California climate, including less variation in temperature, milder winds, and increased rainfall.[22] He was concerned about water conservation, and warned what is now called smog, identifying it as a concern in 1938, well before it gained official recognition in Los Angeles.[23] Widney sought the preservation of three great forest areas for future generations.[24] In January 1873, Widney suggested the Colorado Desert be flooded to re-establish Lake Cahuilla.[25][26][27] Horace Bell criticized the proposal in Reminiscences of a Ranger.[28] In his 1935 book, The Three Americas, Widney said that Atlantis was in the area where the Bahamas are located. He thought it was a semi-tropical island, inhabited by peoples from the Americas rather than from Europe.[29] He also believed that there was a submerged lost continent in the South Pacific Ocean.[30] California developmentWidney saw the potential of Los Angeles on his first visit in January 1867 while posted to Drum Barracks. His brother, Robert Maclay Widney (1838–1929), had arrived in Los Angeles in 1868, and was a lawyer, and later judge, as well as the city's first real estate agent.[31] Robert Widney was also the publisher of The Real Estate Advertiser. Joseph Widney invested in real estate in the Los Angeles area, which made him financially independent, and allowed him to retire from the practice of medicine at 55. In 1900, the Los Angeles Times called him "an extensive property owner in this city".[32] At one time he owned the Widney Block on First Street, another Widney Block at Sixth and Broadway, and a property at the corner of Ninth and Santee streets, where he erected the Nazarene Methodist Episcopal Church.[32] He also owned a building at 445–447 Aliso Street, where the first college of medicine for the University of Southern California was located from 1885 to 1896. His investment in land started early. Between April 29, 1869, and August 28, 1871, he bought thirty-four lots in Wilmington near the San Pedro harbor area and another 60 acres (240,000 m2) near the San Gabriel Mission (Rand 28). He owned the parcel of land where the Los Angeles City Hall now stands, as well as much of Mount Washington, Los Angeles, where his last home (a Victorian mansion at 3901 Marmion Way) stood. During the Los Angeles boom in 1885, Widney bought 35,000 acres (142 km2) of land (75 miles (121 km) northeast of Los Angeles) comprising the relatively undeveloped township of Hesperia, California. Widney formed the Hesperia Land and Water Company to create a town.[33] Horace Bell, in his On the Old West Coast, a personal reflection on that period, critiqued the boomers, as a "speculative conspiracy against all that was honest." No houses were built in "Widneyville."[34] The Los Angeles Times of June 2, 1887 said that Widney had purchased a hotel and several bath houses in the town of Iron-Sulphur Springs, once known as Fulton Wells and now as Santa Fe Springs, fifteen miles (24 km) east of downtown Los Angeles.[35] In 1886 the springs were purchased by the Santa Fe Railroad, which renamed the town after itself.[36] Widney said, "We may look lovingly back on log cabin days, but the looking back must be done over a multi-lane highway, not along a cow track".[37] He supported the development of Los Angeles even at the age of 95. In 1937 he wrote "A Plan for the Development of Los Angeles as a Great World Health Center." To develop Los Angeles, Widney proposed roads and tunnels to cross the Sierra Madre Mountains, linking the city and the interior desert. According to Carl Rand, Widney postulated:

Jaher lists Widney as among those Los Angeles entrepreneurs who were the "most avid civic boosters ... [who] made sanguine by their triumphs, they expect urban growth to bring further gains ... [who] predicted that the city would become a great metropolis".[39] Widney envisioned Los Angeles "developing into the health capital of the world, a heliopolis of holistic health culture".[40] He was a member of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce from October 1888. His first two books promoted California. In California of the South (1888), described by David Fine as "one of the earliest booster tracts"[41] Widney and Walter Lindley wrote: "The health-seeker who, after suffering in both mind and body, after vainly trying the cold climate of Minnesota and the warm climate of Florida, after visiting Mentone, Cannes, and Nice, after traveling to Cuba and Algiers, and noticing that he is losing ounce upon ounce of flesh, and his cheeks have grown more sunken, his appetite more capricious, his breath more hurried, that his temperature is no longer normal, ... turns with a gleam of hope toward the Occident" – by which they meant Southern California. Many people followed that gleam and found it something more than hope".[42] Public serviceWidney helped define the railroad, maritime and commercial policy of Southern California.[43] He and Robert were entrepreneurial professionals. They were "effective lobbyists for the Southern Pacific [railroad] and for harbor improvements"[44] and were "active in transport enterprises and in the development of the San Pedro harbor".[45] In 1871, Widney wanted Los Angeles to have a harbor, and with Phineas Banning successfully lobbied the United States Congress for funding for the harbor at San Pedro, California (the Port of Los Angeles). He was chairman of the Los Angeles Citizens' Committee on the Wilmington Harbor. He successfully opposed the attempt of the railroad interests of Collis Potter Huntington and his partners from claiming the state tidelands of the harbor for their own purposes, ensuring these lands remained in public hands.[46] Widney supported dividing the state of California and establishing the commonwealth of Southern California. He was regarded as "one of the ablest and most enthusiastic advocates of the new 'California of the South'".[47] For many years Widney advocated the division of the state of California into at least two states, in order to maximize its representation in the U.S. Senate.[46] He indicated in 1880 that "the topography, geography, climatic and commercial laws all work for the separation of California into two distinct civil organizations".[48] In 1888, Widney said that "two distinct peoples are growing up in the state, and the time is rapidly drawing near when the separation which the working of natural laws is making in the people must become a separation of civil laws as well".[49] In his book The Three Americas (1935), Widney suggested that the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa form an Anglo-Saxon federation with freedom of migration and a common citizenship. While Republican in general politics, he was "an earnest worker in the cause of temperance".[43] In an 1886 Los Angeles Times op-ed piece Widney suggested that the liquor question – the restriction of its manufacture and sale – should not only become the subject of a Republican party platform plank but should be the issue around which the party rebuilt itself.[50] He was interested in the progress of prohibition, and served as head of the city's nonpartisan anti-saloon league.[51] Widney is regarded as "the outstanding early educator of Los Angeles".[52] He was involved in the University of Southern California from its conception in 1879, and served as a member of the Board of Trustees of USC from 1880 to 1895. He was heavily responsible for the creation of the USC College of Medicine in 1885 at the beginning of a three-year "boom" cycle in Los Angeles, and served as founding dean, a responsibility he accepted for the next eleven years until his resignation on September 22, 1896. According to Michael Carter, "the University Catalogue for the academic year 1884–85 declared that applicants to the medical school, as to the rest of USC, would not be denied admission because of 'race, color, religion or sex.'" After the death of USC founding president Marion McKinley Bovard on December 30, 1891, the board of trustees elected Widney as the second president. After he "recognized a call of the Lord",[53] he accepted the presidency at a difficult time in the history of the young institution, which had only twenty-five undergraduate students with a focus on providing secondary education.[54] The College of Liberal Arts was eighteen thousand dollars in debt. He first set up a separate governing board for the College of Liberal Arts, both to refinance the debt and of tying that branch of the institution more closely to California Methodism.[55] He raised $15,000, giving his own personal security to back up the loans, saving USC from bankruptcy. The Southern California Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church increased its support for USC in 1893. The Conference "enthusiastically adopted Widney's new financial program for the institution. Two of the church's most distinguished and trusted leaders, Widney and Phineas F. Bresee, were at the helm. By the time of the annual conference of 1894, the university had passed through its financial crisis, and Widney's principal work was done".[56] In the spring of 1895, Widney resigned after "four years of intensive unremunerated service to the university as its president".[57] He announced his intention to spend a year studying in the East. The board finally accepted the resignation, after their benefactor had turned aside repeated requests that he reconsider his decision.[58] In addition to his responsibilities at USC, Widney served several years as a member and president of the Los Angeles Board of Education.[56] In October 1894 at the dedication of the Peniel Hall, Widney announced his intention to organize a Training Institute, in which Bible and practical nursing were to be the principal studies.[59] Religious interestsWidney was raised in the Greene Street Methodist Episcopal Church in Piqua, Ohio.[60] His uncle, Robert Samuel Maclay, was the first Methodist missionary to China, and an early Methodist missionary to Japan and Korea.[61] In the Los Angeles First Methodist Episcopal Church, the Widneys were members of the "District Aid Committee," an organization devoted to securing better support for underpaid pastors.[62] He supported the Los Angeles City Mission (the Peniel Mission), founded in 1886 as the Los Angeles Mission[63] and was non-denominational and nonsectarian.[64] Bresee and Widney wanted a church for the poor. They announced a service for October 6, 1895, in Red Men's Hall near the Peniel Mission.[65] On October 30, 1895, Bresee and Widney organised the Church of the Nazarene.[66] Widney suggested the name of the new church.[67] Widney returned to the Methodist church as a pastor and was appointed to the church's City Mission of Los Angeles (formally organized in 1908), where he ministered to thousands over the next several years. In 1899, he was the pastor of the Nazarene Methodist Episcopal Church. Growth of the congregation led to the building of a 500-seat building. He paid the full cost of construction and ministered without compensation. The new building was dedicated on June 3, 1900.[68] In 1903 this church was renamed the Beth-El Methodist Episcopal Church.[69] Widney resigned from the Methodist Episcopal church in 1911. Widney was influenced by the teachings of preacher David Swing and Thomas Starr King, a broad-minded, religiously inclusive Unitarian minister. Widney described King as "one of the few great and broad-minded spirits of the church" (Frankiel, p30.)California's Spiritual Frontiers. Racial beliefsWidney lamented the decline in influence and power of the original Hispanic population of California. Widney said, "You could visit the hospitals and almshouses in the late 'eighties and look in vain for the Mexican or the Spaniard."[70] Widney in his 1876 History indicates: "In the spring of 1850, probably three or four colored persons were in the city. In 1875, they numbered 175 souls, many of whom hold good city property acquired by industry. They are farmers, mechanics, or some other useful occupation, and remarkable for good habits".[71] African-American activist W. E. B. Du Bois used Widney's Race Life of the Aryan Peoples to support his own view of the significance of the contributions of blacks to the development of modern civilization. Widney wrote "They [the Negroes] once occupied a much wider territory and wielded a vastly greater influence upon earth than they do now."[72] In The Three Americas (1935), Widney suggested that the United States buy British Guiana from the United Kingdom and give it to the African Americans as reparations for slavery.[73] Later years Widney attributed his longevity to living simply and keeping busy.[74] At age 94, Widney advocated "no liquor, no tobacco, no drugs. I'm not a fanatic on liquor, but to me it is a medicine. I keep it around and take it when I need it. But there is no excuse whatever for tobacco or drugs".[75] He recommended at least eight hours sleep each night and short naps throughout the day.[76] He died at 10:50 am on July 4, 1938, in his home in Highland Park, Los Angeles, aged 96. After services held in his home, he was buried at the Evergreen Cemetery at Boyle Heights on July 6, 1938. In March 1939 the new Crippled Children's High School was renamed the Dr. Joseph Pomeroy Widney High School. This school is for those aged 13 to 22 with special educational needs. The Widney Alumni House at the University of Southern California,[77] the university's original building, was declared a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (No. 70) on December 16, 1970.[78][79][80] The University of Southern California honors its distinguished graduates by presenting the Widney Alumni Award. His portrait was painted by American artist Orpha Mae Klinker,[81] and a bust of Widney was sculpted by Emil Seletz.[82] List of worksBooks (co-authored)

References

Further reading

Books

Theses and dissertations

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Joseph Widney. |