|

Joseph Watt

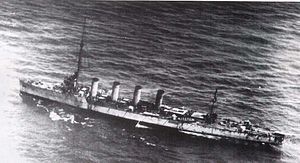

Joseph Watt, VC (25 June 1887 – 13 February 1955) was a Scottish recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He achieved the award during service in the Strait of Otranto and as a result of his meritorious service also received the French Croix de Guerre[1] and the Italian Silver Medal for Military Valour.[2] Early lifeJoseph Watt was born in 1887 in the Scottish fishing village of Gardenstown on the Moray Firth, into the large family of Joseph Sr. and Helen Watt. His father was a fisherman of many years service and his mother was also employed in the fish industry. At age ten his father was lost at sea in an accident, and the family moved to Fraserburgh in Aberdeenshire where his mother remarried. He learned the fishing trade from an early age and served aboard the White Daisy before purchasing a stake in the drifter Annie. The war changed life in the community as most of the menfolk volunteered for service with the Royal Navy on the patrol service, hunting for enemy shipping and submarines, often in small drifters and trawlers similar to the ones they sailed in every day. Joe was no exception, being rated a skipper in the patrol service, and marrying Jesse Ann Noble in the days before his posting overseas. Transferred to Italy in 1915, Watt served on drifters in the Adriatic Sea, enduring boring patrol work keeping Austrian submarines from breaking into the Mediterranean Sea. During this time he was highly commended, for his role in the operation to evacuate the remnants of the Serbian Army following their defeat and retreat to Albania in January 1916 for which he was later awarded the Serbian Gold Medal for Good Service.[3] Shortly before Christmas 1916, Watt's drifter, HM Drifter Gowanlea was attacked by an Austrian destroyer sortie, which was attempting to break the line of drifters and allow submarines to escape into the Mediterranean. Although hit several times by shellfire, the drifter was not seriously damaged and the crew unhurt. It was however a mild precursor to a major raid planned against the Otranto Barrage as the drifter line was now called. Victoria Cross actionOn 15 May 1917 Skipper Watt and his crew of eight men and a dog were patrolling peacefully in the Otranto Strait on the lookout for any suspicious activity following an increase in submarine sightings. Unbeknownst to the allied line, the Austrians had planned a major operation against the barrage, utilising the Rapidkreuzers SMS Saida, Helgoland and SMS Novara under Admiral Miklós Horthy with two destroyers and three submarines. These ships fell upon the drifter line during the night and sank 14 trawlers and drifters which were helpless to reply, as well as two destroyers.  Gowanlea was confronted by the Helgoland, which demanded the surrender of the tiny ship and ordered the crew to abandon ship prior to sinking. Instead, Watt ordered his crew to open fire on their large opponent with the drifter's tiny 6-pounder guns. Gowanlea was quickly hit by four heavy shells, seriously damaging the boat and wounding several crewmen. The other drifters around Gowanlea followed her example but were also subject to heavy fire, three sinking and the last lurching away seriously damaged. The Austrian cruisers headed for home but were engaged on their return by British, Italian and French units and became involved in the inconclusive battle of the Otranto Barrage. For Watt and the survivors on their battered boats and in the water the fight now was with the sea, as Gowanlea, despite her own heavy damage and casualties moved amongst the wreckage, rescuing wounded men and providing medical attention to those in most need. In particular Watt saved the wounded crew of the sinking drifter Floandi who otherwise may have drowned. The awardThere was some dispute at the time as to whether the award of the Victoria Cross was appropriate given the defeat suffered by the barrage despite the resistance against overwhelming odds[4] In the event, Watt was the only recipient of the men put forward from the drifter crews although several other men were given the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal or the Distinguished Service Medal, including three from Gowanlea's crew. Watt was characteristically uncomfortable with his award, commenting on a request for an interview postwar with the words "There has been too much said already and it should get a rest ... I'm ashamed to read the exaggerations which have been printed".[4] He was moved from drifters shortly after the action, becoming sick and spending the remainder of the year in hospital in Malta before being brought home to receive his award at Buckingham Palace and serve on light duties as a Chief Skipper.[5] Citation

Third Supplement to the London Gazette of Tuesday, 28 August 1917[6] Post-War LifeJoe Watt returned to Fraserburgh after the war and refused point blank to ever speak of his war experience again, even to his wife. His boat Annie had been lost in the war to a sea mine, and so he bought Benachie as a replacement, on board which he once forgot to remove his cap on meeting the Duke of Kent, an omission which mortified him for years afterwards.[4] He served on several other fishing vessels over the next twenty years before joining the Navy again as a drifter captain to serve in the Second World War, which he spent on uneventful duties in home waters accompanied by his son who had been wounded in the Battle of France serving with the Gordon Highlanders and invalided out of the army. He was on occasion heard to complain that he had been refused foreign service due to his age, which he seemed to feel should be an advantage rather than a hindrance.[4] Joe Watt died of cancer at home in 1955 and was buried alongside his wife and in-laws at Kirktown Cemetery in Fraserburgh. His passing was remarked on by a local politician who visited him and said of the experience that "He had wonderful faith and courage".[4] The medalWatt, who always shunned the fame generated by his award, kept the medal in a drawer full of junk on board his boat. Many of the locals who requested to see the medal were surprised to see it being kept in such a place. His VC medal was placed in auction in April 2012[7] but can now be seen at the Imperial War Museum, London. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||