|

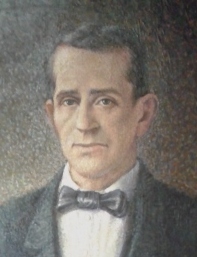

José María Cañas

José María Cañas Escamilla (September 23, 1809—October 2, 1860) was a Salvadoran military figure. He was born in Suchitoto, El Salvador.[1][2][3] BiographyHe moved to Costa Rica in 1842 along with General Francisco Morazán,[4] where he married Guadalupe Mora Porras, sister of President Juan Rafael Mora Porras.[5] He was Costa Rica's Customs Administrator in 1844 and also became State General in 1847. He was named Secretary of War during Juan Rafael Mora Porras's presidency in 1849 and eventually became Governor and Commander of Puntarenas in 1850.[6] Named as a general in 1856, he commandeered the Costa Rican Army[6] during the third and most important part of the campaign against filibuster William Walker. He was known as an affable and kind person amongst his troops. Cañas was also responsible for the development of Costa Rica's Pacific Ocean port, Puntarenas, where he served as commander for several years. In 1855, Cañas imported 32 Chinese laborers to Puntarenas near the Nicoya Peninsula, employing many of them as laborers on his estates.[7] A benevolent patron to these workers, Cañas's memory is, to this day, held in high remark by many of their descendants. Years after Cañas's death, his children were still well received in Puntarenas by members of the thriving Chinese-Costa Rican community. In representation of Costa Rica he signed the Cañas-Jerez Treaty, the Cañas-Martínez Treaty and the Cañas-Jerez Treaty that dealt with the demarcation of the border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua[8][9] and U. S. President Grover Cleveland also validated the treaty.[10] In 1859, when his brother-in-law was deposed, he emigrated back to El Salvador with him. The following year they returned to Costa Rica seeking the restoration of Mora Porras in the presidency. The expedition failed and they both died in Puntarenas after being captured by troops now controlled by President José María Montealegre, and those troops who were once Cañas's, threatened to shoot and kill him.[11] Juan Rafael Mora Porras was executed by firing squad on September 30; Cañas was killed using the same method on October 2, 1860.[12] Cañas was the last prominent Costa Rican leader to face the death penalty as the victim of political persecution. Two decades after the execution of Cañas, President Tomás Guardia, who had served under his command in 1856, abolished the death penalty. Several years after Cañas' execution his widow and their children returned to Costa Rica. The family thrived and was welcomed once again into the country's highest spheres. Cañas' only surviving son, Rafael Cañas Mora, served in the Costa Rican congress and was a successful businessman. Other Cañas descendants include Dr. Luciano Beéche Cañas, a Costa Rican doctor; Rafael Beéche Cañas, founder of the tuna fishing industry in Costa Rica; Eduardo Beéche Titzck, former governor of the state of Puntarenas; Arturo Beéche Bravo, author, educator and royal historian; Alberto Cañas Escalante,[13] author, intellectual and politician; Marta Castegnaro Cañas, newspaper columnist and historian. Cañas is considered a national hero[1][14] and there is a monument bust of him in Parque Cañas, a park which was named for him in 1956 and the dedication ceremony was attended by his great-grandson Alberto Cañas Escalante, the centennial of the Filibuster War,[15] in Puntarenas in front of the railroad Ferrocarril Eléctrico al Pacífico.[1] References

|

||||||||||||||