|

John Stevens (inventor, born 1749)

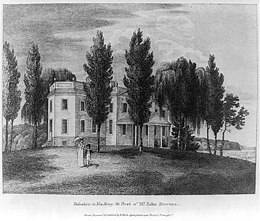

Col. John Stevens, III (June 26, 1749 – March 6, 1838) was an American lawyer, engineer, and inventor who constructed the first U.S. steam locomotive, first steam-powered ferry, and first U.S. commercial ferry service from his estate in Hoboken. He was influential in the creation of U.S. patent law. Early lifeStevens was born June 26, 1749, in New York City, New York.[1][failed verification] He was the only son of John Stevens Jr. (1715–1792), a prominent state politician who served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, and Elizabeth Alexander (1726–1800). His sister, Mary Stevens (d. 1814), married Robert R. Livingston, the first Chancellor of the State of New York.[2] His maternal grandparents were James Alexander (1691–1756), the Attorney General of New Jersey, and Mary (née Spratt) Provoost Alexander (1693–1760), herself a prominent merchant in New York City. His paternal grandfather, John Stevens, emigrated from London England around 1695, and was married to Mary Campbell.[3] He graduated King's College (which became Columbia University) in May 1768.[3] CareerAfter his graduation from King's College, he studied law and was admitted to the bar of New York City in 1771. He practiced law in New York and lived across the river.[3] At public auction, he bought from the state of New Jersey a piece of land which had been confiscated from a Tory landowner. The land, described as "William Bayard's farm at Hoebuck" comprised approximately what is now the city of Hoboken. Stevens built his estate at Castle Point, on land that would later become the site of Stevens Institute of Technology (bequeathed by his son Edwin Augustus Stevens).[4] During the 1830s, he developed the land around his estate into the Elysian Fields, a popular weekend recreational and entertainment destination for New Yorkers during the 19th century.[citation needed] Stevens bought a farm in Dutchess County, New York from John Armstrong Jr. Armstrong had converted a barn into a two-story Federal style dwelling with twelve rooms. Stevens made improvements to the estate, including a half-mile race track.[5] He later sold the property to John Church Cruger (1807–1879), husband of Euphemia Van Rensselaer, daughter of Stephen Van Rensselaer. The Crugers named the estate "Annandale".[citation needed] In 1776, at age 27, he was appointed a captain in Washington's army in the American Revolutionary War. During the War, he was promoted to colonel and became Treasurer of New Jersey, serving from 1776 to 1779.[3] In 1789, Stevens was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[6] In 1790, Stevens petitioned Congress for a bill that would protect American inventors. Through his efforts, his bill became a law on April 10, 1790, which introduced the patent system as law in the United States,[3] patent law.[7] In 1799, Stevens was named to the Board of Directors of the Manhattan Company. As one of the original stockholders and directors of The Manhattan Company, Stevens was appointed to a three-person committee, along with John B. Coles and Samuel Osgood, to explore the best ways to supply water to New York City. He ultimately became the company’s consulting engineer and succeeded in convincing his fellow directors that steam pumping engines should be used and installed. SteamboatsIn 1802, Stevens designed and a built a single screw steamboat using a rotary steam engine, a primitive single stage turbine. However, due to poor sealing, the design was abandoned and he would switch to using more conventional reciprocating engines for future steamboats.[8] In 1804, Stevens built the Little Juliana, a twin screwed steamboat. She was one of the first steamboats to incorporate twin screws and a high pressure steam engine. She successfully sailed down the Hudson in May 1804.[8] In 1806, he built the Phoenix, a steamboat that ultimately sailed from Hoboken to Philadelphia in 1809, thereby becoming the first steamship to successfully navigate the open ocean.[9] In October 1811, Stevens' ship the Juliana began operation as the first steam-powered ferry (service was between New York City, and Hoboken, New Jersey).[10] The first railroad charter in the U.S. was given to Stevens and others in 1815 for the New Jersey Railroad. The charter essentially gave Stevens and his partners, through the Camden & Amboy Railroad, a monopoly on railroads in the state of New Jersey.[11] In 1825, he designed and built a steam locomotive, which he operated on a circle of track at his estate in Hoboken, New Jersey.[1] Personal life On October 17, 1782, he married Rachel Cox (1761–1839), the daughter of John Cox. She was a descendant of the Langeveldts (or Longfields) who originally settled New Brunswick, New Jersey.[12] Together, they had thirteen children of which seven were sons. The children included:[12]

Stevens died on March 6, 1838, at his estate in Hoboken, New Jersey.[3] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||