|

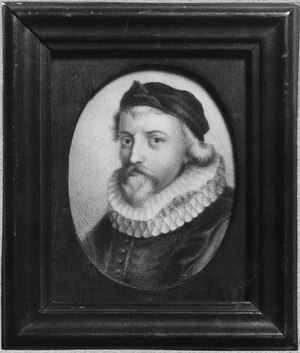

Johannes van der Beeck

Johannes (Jan) Symonsz van der Beeck (1589 – buried 17 February 1644) was a Dutch painter also known by his alias Johannes Torrentius. ("Torrentius" is a Latin equivalent of the surname van der Beeck, meaning "of the brook" or "of the river".) Despite his reputation as a still life master, few of Torrentius' paintings survive, as his works were ordered to be burned after he was accused of being a Rosicrucian adherent of atheistic and Satanic beliefs.[dubious – discuss] The tortured painter was thrown into prison as a convicted blasphemer until being permitted to leave the country as a political gesture for England's Charles I, an admirer of van der Beeck. Life and career Johannes van der Beeck was born and died in Amsterdam, where he married in 1612. Relations between himself and wife Neeltgen van Camp eventually soured and ended in a divorce. Van der Beeck was briefly thrown into jail for failing to pay alimony to his former wife in 1621.[1] His libertine ways and purported membership in the Rosicrucian order led to his 1627 arrest and torture as a religious non-conformist and an alleged blasphemer, heretic, atheist, and Satanist.[citation needed][dubious – discuss] The 25 January 1628 judgment from five noted advocates of The Hague pronounced him guilty of "blasphemy against God and avowed atheism, at the same time as leading a frightful and pernicious lifestyle".[2] It was widely believed that the condemned Torrentius' influence had affected Jeronimus Cornelisz, a trader of the Dutch East India Trading Company who led a bloody mutiny aboard the Batavia, a ship of the Dutch East India Company, in 1629.[3] According to the RKD, Torrentius was tried in 1627,[4] but according to Houbraken, who quoted Theodorus Schrevelius, he was tried and placed on the painbench, and thereupon sentenced to 20 years in the Tuchthuis (the Haarlem house of detention), on 25 July 1630.[5][6] Although he was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment, King Charles I of England – an admirer of the painter's works – intervened, and was able to secure his release after two years, hiring Torrentius as Court Painter. He stayed in England for 12 years, returning to Amsterdam in 1642.  LegacyThe painting Still life with Bridle inspired Polish poet and essayist Zbigniew Herbert to write an essay on Torrentius and this picture entitled "Still life with Bridle" which also gave its title to his collection of essays on Dutch Golden Age painting (Wrocław, 1993). In the documentary Mysterious Masterpiece: Cold Case Torrentius (2016) by Maarten de Kroon in cooperation with Jeanne van der Horst, Torrentius's sole remaining painting Still life with Bridle is submitted to a close technical investigation. A series of experts (including Christopher Brown, Walter Liedtke and Martin Kemp) comment on the artist's technique and life story. The film details the technical research shedding new light on Torrentius's work.[7] References

External links

|