|

Jean de Carrouges

Sir Jean de Carrouges IV (c. 1330s – 25 September 1396) was a French knight who governed estates in Normandy as a vassal of Count Pierre d'Alençon and who served under Admiral Jean de Vienne in several campaigns against the Kingdom of England. He became famous in medieval France for fighting in one of the last judicial duels permitted by the French king and the Parlement of Paris (the actual last duel occurred in 1547[1] opposing Guy Chabot de Jarnac against François de Vivonne). The combat was decreed in 1386 to contest charges of rape Carrouges had brought against his neighbour and erstwhile friend Jacques Le Gris on behalf of his wife Marguerite. Carrouges won the duel. It was attended by much of the highest French nobility of the time led by King Charles VI and his family, including a number of royal dukes. It was also attended by thousands of ordinary Parisians and in the ensuing decades was chronicled by such notable medieval historians as Jean Froissart, Jean Juvénal des Ursins, and Jean de Waurin. Described in the chronicles as a rash and temperamental man, Carrouges was also a fierce and brave warrior whose death in battle came after a forty-year military career in which he served in Normandy, Scotland and Hungary with distinction and success. He was also heavily involved in court politics, initially at the seat of his overlord Count Pierre of Alençon at Argentan, but later in the politics of the royal household at Paris, to which he was attached as a chevalier d'honneur and royal bodyguard in the years following the judicial duel. During his life, he conducted a long trail of legal and financial dealings which infuriated his contemporaries and may have invited violence against him and his family. The truth of the events which led him into public mortal combat in the Paris suburbs may never be known, but the legend is still debated and discussed 600 years later. Early lifeCarrouges was born in the late 1330s in the village of Sainte-Marguerite-de-Carrouges as the eldest son of the knight and minor noble, Sir Jean de Carrouges III, and his wife, Nicole de Buchard.[2] Jean was an influential man in lower Normandy, being a vassal of the Count of Perche and a veteran soldier in his service.[3] He had been rewarded for his long military service in the Hundred Years' War with a knighthood and the title of Viscount of Bellême, a rank that came with command of a vital hill castle overlooking the town as well as the role of sheriff in the vicinity, a post carrying significant financial and social rewards.[4] Carrouges IV grew up within his father's domain, centred around the village of Carrouges where the family maintained their own hereditary castle.[5] He followed his father into the armed service of the Counts of Perche and served in several minor campaigns against the English and routiers in Normandy. Following his majority at age 21, he was given a parcel of the family lands to administer and became interested in solidifying and expanding the family holdings. In 1367 the family castle and the village of Carrouges were destroyed by English soldiers and a new castle was built on a hilltop nearby, under instructions from Charles V of France.[5] In the early 1370s, Carrouges IV married Jeanne de Tilly, a daughter of the Lord of Chambois whose dowry included lands and rents vital to Carrouges' ambition of expanding his family estates. Shortly after their wedding, Jeanne gave birth to a son, whose godfather was a neighbour and close friend of de Carrouges, Squire Jacques Le Gris. In 1377, Pierre d'Alençon inherited his brother Robert's county of Perche and with it the castle of Bellême. In addition, he gained the fealty of his brother's vassals, including the Carrouges father and son as well as Jacques Le Gris. The younger Carrouges and Le Gris soon joined the court circle of the Count, centered around the town of Argentan.[6] It was at Argentan that the friendship between Carrouges and Le Gris began to deteriorate, as Le Gris rapidly became a favourite of Count Pierre. While Carrouges was overlooked, Le Gris was rewarded for service to the Count, inheriting his father's lordship of the castle at Exmes and being granted a newly purchased estate at Aunou-le-Faucon. Carrouges became jealous of his friend and the two men soon became rivals at the court.[7] A year after entering Count Pierre's service, tragedy struck Carrouges as both his wife and son died of unknown but natural causes. In response, Carrouges left home and joined the service of Jean de Vienne accompanied by a retinue of nine squires.[8] With this force, under the overall command of King Charles V, Carrouges distinguished himself in minor actions against the English in Beuzeville, Carentan, and Coutances in a five-month campaign, during which over half his retinue were killed in battle or by disease.[8] Marguerite de ThibouvilleReturning home in 1380 after a successful campaign, Carrouges married Marguerite de Thibouville, the only daughter of the highly controversial Robert de Thibouville. De Thibouville was a Norman lord who had twice sided against the French king in territorial conflicts, betrayals he was lucky to survive, albeit in reduced circumstances. By the union of Marguerite and Carrouges, de Thibouville hoped to restore his family's status while Carrouges was hoping for an heir from the young Marguerite, whom contemporaries described as "young, noble, wealthy, and also very beautiful".[9] Shortly after his marriage, Carrouges revealed another motive for the union. The valuable estate of Aunou-le-Faucon, given to his rival Jacques Le Gris two years earlier, had been formerly owned by Carrouges' father-in-law, Robert de Thibouville, and had been bought by Count Pierre for 8,000 French livres in 1377. Carrouges immediately began a lawsuit to recover the land, based on an assumed prior claim to it.[10] The case dragged on for some months until ultimately Count Pierre was forced to visit his cousin King Charles VI to confirm his ownership of the land officially, as well as his right to give it to whomever of the followers he chose. The lawsuit reflected very poorly on Carrouges at the court in Argentan and resulted in his further estrangement from Count Pierre's circle.[10]

Two years after the Aunou-le-Faucon lawsuit, Carrouges was once again in court facing Count Pierre, this time in a dispute over the lands administered by his recently deceased father. Carrouges III's death early in 1382 vacated the captaincy of the castle of Bellême, a post Carrouges IV believed would be his by right. However, due to the failed lawsuit two years earlier, Count Pierre passed Carrouges over for the captaincy and gave it to another of his followers. The infuriated Carrouges again brought legal action against his overlord and again he was defeated in court. The only lasting result of the action was the further separation of Carrouges and Count Pierre's court.[12] In March 1383, Carrouges made a third effort to expand his family holdings, with the purchase of the neighbouring fiefs of Cuigny and Plainville from his neighbour Sir Jean de Vauloger. The sale required approval from Count Pierre, who was overlord of both fiefs, but as a consequence of the previous legal difficulties Carrouges had caused him, he refused to permit the sale and insisted that Carrouges turn the properties over to him in exchange for a full refund of the original price paid.[13] Carrouges had no choice but to comply and subsequently blamed Jacques le Gris' influence for this new misfortune.[13] Campaigning in Scotland Late in 1384, Carrouges entered society for the first time since his marriage four years earlier, attending a party to celebrate the birth of a neighbour's son. Carrouges and Le Gris met at the celebration and agreed to end their quarrel, Carrouges introducing Le Gris to his wife Marguerite for the first time.[14] A few months after this meeting, in March 1385, Carrouges attempted to increase his family wealth through military means, by joining the army of Jean de Vienne for an expedition sailing to Edinburgh. This force of about 3,000 soldiers was intended to unite with the Scottish army and raid Northern England, distracting English forces from operations in France. Travelling with men-at-arms, horses, gold, and equipment, Carrouges and his entourage rode to Sluys and took ship to Leith during the spring of 1385.[citation needed] On arrival in Scotland, much time was spent gathering Scottish troops together for the campaign on England, and the French were delayed for some months collecting supplies.[15] The army thus did not move south until July, ravaging villages and farms in the region of the River Tweed before besieging Wark Castle and burning it to the ground. The allied army then continued south through Northumberland and there burned villages, towns, farms, and castles across their line of advance in a large chevauchée.[16] The English responded with an army led by King Richard II which advanced against the allied force and offered battle. The French prepared to fight but their Scots allies retreated, leaving the French exposed, and they were consequently forced to retreat as well.[17] Outside Edinburgh, the Scottish army dispersed and the inhabitants of the city fled north, leaving the French alone. Realising that his force was outnumbered and without food or help, Vienne took the army south, rounding the English on the night of 10 August and reentering Northumberland for further looting, attacking Carlisle but being unable to break through its walls.[18] As the Franco–Scottish forces returned northwards it was attacked by an army under Henry Percy which destroyed their wagon train and took many prisoners. When the defeated French returned to Edinburgh the Scots refused to provide for the French army and many men died of disease or starvation. Late in the year, the French army boarded ships and returned to Flanders, bankrupt and defeated.[16] Despite the expedition's failure, Carrouges had distinguished himself in the campaign. Although he had lost five of his nine men-at-arms and a substantial amount of money, he had also been awarded a knighthood on the battlefield, substantially raising his social status and the amount of money he received from military service.[19] Despite being in poor health on his return from Scotland, Carrouges had business in Paris and in January 1386 he travelled there to collect his wages for the previous year's campaign, leaving his wife with his mother at the village of Capomesnil. Rape of Marguerite

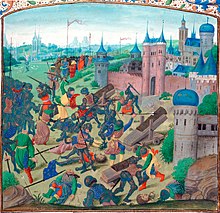

Before setting off for Paris, Carrouges first visited Argentan to meet with Count Pierre and there announced his intention of continuing to the capital. What followed was a sequence of events that remain unclear, but which would have a dramatic effect on the lives of all concerned.[20] What is certain is that Carrouges encountered his rival Jacques Le Gris at the court of Count Pierre and words were exchanged, although what was said is unknown.[21] In contrast to his bankrupt rival, Le Gris had not been on the Scottish expedition and had grown wealthier in Carrouges' absence. Le Gris also had a reputation as a fierce and strong soldier in addition to that of a notorious womaniser, a reputation that may have played a part in the allegations that followed.[7] On the morning of 18 January 1386, Dame Nicole de Carrouges departed her chateau at Capomesnil for the neighbouring town of Saint-Pierre-sur-Dives where she had legal business to attend to. Although the journey was only a short one, she apparently took some or all of the household servants with her, leaving her daughter-in-law unattended during the day.[22] Marguerite's testimony then alleged that a man-at-arms named Adam Louvel knocked on the chateau door, which Marguerite opened herself in the absence of servants. According to Marguerite, Louvel then made inquiries about a loan he owed Jean de Carrouges before suddenly announcing that Jacques Le Gris was outside the door and insisted on seeing her. At her refusal, Louvel exclaimed that "he loves you passionately, he will do anything for you and he greatly desires to see you".[23] Although Marguerite protested, Le Gris then forced his way into the house and propositioned her, offering money if she would remain silent if they had an affair. When Marguerite refused, Le Gris then violently raped her with the aid of Louvel and threatened her not to tell anyone what had occurred on pain of death.[24] Marguerite remained silent about her ordeal for several days, until her husband's return on the 21 or 22 January.[6] Upon hearing of the encounter, the outraged Carrouges summoned his circle of courtiers and friends, including his mother and most of Marguerite's family, and a council was convened where Marguerite repeated her account of the rape.[25] Carrouges decided immediately to begin legal proceedings against Le Gris but faced great difficulties in prosecuting them as Le Gris was a favourite of Count Pierre, who would act as judge in the case. In addition, the case was viewed as weak in this time period because the only witness was Marguerite. Indeed, the trial at Argentan was so one-sided an affair that Carrouges and his wife did not even bother to attend. Pierre acquitted Le Gris of all charges and furthermore accused Marguerite of inventing or even "dreaming" the attack.[26] Legal proceedings In search of a fair trial, Carrouges travelled to Paris to appeal to the King himself. Knowing that his case depended solely on his wife's testimony and was, therefore, her word against Le Gris, Carrouges developed a plan. Instead of proceeding with a normal criminal trial, Carrouges would challenge Le Gris to a judicial duel, the survivor of which would thus have been deemed by God to have been the rightful claimant.[27] Such trials-by-combat, once common in France, were rare by 1386 and the chance of one being permitted by the King unlikely. Nevertheless, Carrouges saw this scheme as his best option for procuring justice and redeeming his wife's reputation.[28] A few days after his arrival in Paris, Carrouges was presented to the King at the Château de Vincennes in order to make the first official appeal in the lengthy trial process. In doing so, he captured the imagination of the French court, which later became so fascinated with the Carrouges-Le Gris trial that it would shape its schedule around watching the culminating combat.[29] On 9 July 1386, the second stage in the legal process began when both Carrouges and Le Gris, with their followers, presented themselves before the Parlement of Paris at the Palais de Justice to issue the formal challenge. This involved reciting their accusations and throwing down a gauntlet signifying their intention to fight. The declarations were pronounced in front of the King, his brother Louis of Valois and the entire Parlement, who decided to initially hear the case as an ordinary criminal one and defer their decision on whether to permit the judicial duel until both sides had given testimony.[30] Attempts had been made to persuade Le Gris to insist on a church trial, but these proved unsuccessful as Le Gris wished to counter the accusation with a lawsuit against his opponent claiming 40,000 livres for defamation.[31] Following the declarations a number of high-ranking noblemen stepped forward to act as seconds in the duel for both men, including Waleran of Saint-Pol for Carrouges and Philip of Artois, Count of Eu for Le Gris.[32] The criminal trial continued for most of the summer and Carrouges, Le Gris, and Marguerite were all called on to give evidence. Marguerite was by this time visibly pregnant, although medieval medical knowledge claimed that children could not be conceived as a result of rape and her condition, therefore, was determined to have no bearing on the case.[33] Adam Louvel and at least one of Marguerite's maidservants also gave evidence and, as was the custom of the day for people of low birth, they were tortured to test the veracity of their testimony.[34] During this process neither produced evidence incriminating Le Gris, although Louvel himself was subsequently challenged to a duel by Marguerite's cousin, Thomin du Bois.[34][35] In his evidence, Carrouges' statement repeated and supported his wife's testimony, while Le Gris accused Carrouges of inventing the charges and beating his wife into making the accusations against the squire.[36] In his statement, Le Gris painted a picture of a man driven wild with anger and jealousy who sought to restore his family fortune by concocting false accusations against his most significant rival. Le Gris also offered alibis for his whereabouts during the week the crime was supposed to have been committed and attempted to explain that it was not possible for him to have ridden the 40 kilometres (25 miles) that supposedly separated him from Marguerite on the morning in question.[36] A rebuttal from Carrouges emphasised the shame the trial had brought to his family as a reason against its invention and offered a counter-demonstration of horsemanship indicating that the suggested 80-kilometre (50-mile) round trip was possible even if Le Gris' alibi were true.[37] Le Gris' alibi was compromised some days later when the man providing it, a squire named Jean Beloteau, was arrested for committing rape in Paris during the trial.[29] On 15 September, with the King in Flanders preparing for an invasion of England, the parliament handed down its verdict. As they had been unable to determine the guilt in the case, the two men would fight a duel to the death on 27 November 1386.[6] Trial by combatThe two months following the verdict were ones of great activity between the two parties and the citizens of Paris. As judicial duels were now so rare, no established battleground had been set aside, and a jousting arena at the Abbey of Saint-Martin-des-Champs north of the city agreed to host the combat.[38] Both Carrouges and Le Gris endured bouts of illness in the weeks following the verdict but recovered with the aid of their families and supporters, who had joined the hundreds of people flocking to the city from nearby regions to witness the fight.[39] Indeed, the event was so popular that when King Charles VI believed that his return to Paris in time for the combat would be held up in Flanders due to bad roads, he sent a fast messenger to Paris delaying the duel by a month in order that he would be present to witness it. This royal intervention set the date for the combat back to 29 December 1386.[29] In the months between trial and duel, Marguerite and the French queen Isabeau of Bavaria had both given birth to sons. While Marguerite's son Robert was a strong, healthy boy, the Dauphin was a sickly child and died on 28 December. Rather than descend into mourning, the King ordered a frenzy of parties and celebrations, the pinnacle of which was intended to be the duel between Carrouges and Le Gris.[40] The morning of the combat saw thousands of Parisians arriving at the Abbey at dawn, long before the appointed hour. Among the spectators were the King and his entourage, including his uncles John, Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold and Louis II, Duke of Bourbon as well as his brother the Duke of Orléans.[11] Also present, dressed in black and sitting in a carriage overlooking the field, was Marguerite. Should her husband have lost the battle, she would have been burned at the stake in Montfaucon immediately following the duel, having been thus "proven" guilty of perjury by its outcome.[41] The combatants took the field in the early afternoon, mounted and dressed in plate armour. Both carried a lance, longsword, a heavy battle axe known as the "Holy Trinity" and a long dagger called the "misericordia". Carrouges appeared first, reciting his charges against Le Gris to the King and crowd before Le Gris followed and did the same. Le Gris was then knighted in order that he and Carrouges be of equal standing during the fight. Both knights then dismounted and gave oaths to God, the Virgin Mary and St George, thereby sanctifying God's judgment over the duel's outcome. Finally, Carrouges approached his wife and pledged his honour before her, kissing her and promising to return.[41] As the field was cleared, silence descended on the arena following the King's instructions that anybody who interfered in the duel would be executed and that anyone who shouted or verbally interrupted the combat would lose a hand.[42] Readying their steeds, the knights squared up and at the marshal's signal, charged towards one another. Their lances struck but failed to penetrate the thick hides covering their shields and the combatants wheeled and charged again, this time striking one another on their helms. Rounding once more, the knights charged a third time, again striking shields and this time both shattering their lances. Reeling from the impact, the warriors drew their axes and charged a fourth time. Slashing and kicking at one another in the centre of the field, they traded blows until Le Gris, the much stronger man, was able to drive his axe through the neck of Carrouges' horse. As the beast fell to the ground, Carrouges jumped clear and lashed out with his own weapon, disembowelling Le Gris' steed in turn.[43]

Now on foot, the knights drew swords and returned to battle. Le Gris, again proving stronger than his opponent, slowly gained the upper hand.[43] After several minutes of engagement, Carrouges slipped and Le Gris was able to stab his rival through the right thigh. As the crowd gasped and murmured, Le Gris stepped back. Carrouges used the opportunity to grab the top of Le Gris' helmet and topple him to the ground. Le Gris' heavy armour prevented him from regaining his feet and Carrouges repeatedly stabbed at his floored opponent, his blows denting but not puncturing the thick plate steel.[6] Realising that his sword was inadequate, Carrouges straddled Le Gris and used the handle of his dagger to smash the lock holding Le Gris' faceplate. Even as his opponent struggled beneath him, Carrouges broke the pin holding the lock and tore his faceplate off, exposing Le Gris. Carrouges demanded that Le Gris admit his guilt. Le Gris refused and cried out "In the name of God and on the peril and damnation of my soul, I am innocent". Unable to obtain a confession (which would have condemned Le Gris anyway), Carrouges drove a dagger through Le Gris' neck, killing him nearly instantly.[11] Standing over his vanquished opponent, Carrouges remained on the field as the crowd cheered him and pages rushed to bind his wound.[44] He then kneeled before the King, who presented him with a prize of a thousand francs in addition to a royal income of 200 francs a year.[11] Only then did he greet his wife in an emotional scene before the thousands of spectators.[44] With the crowd following in a great procession, Jean and Marguerite de Carrouges then rode from the abbey to the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, to give thanks for the victory.[11] A few weeks after the duel, Parliament awarded Carrouges a further six thousand livres in gold and a position within the Royal Household. Such rewards enabled Carrouges to begin further legal action, attempting to exert his earlier claim to Aunou-le-Faucon. However, the land which Carrouges so coveted remained beyond his reach. Count Pierre, who held the land, never forgave Carrouges for the death of his favourite advisor and held the estates from him in court.[45] Royal serviceOver the next three years, Jean and Marguerite de Carrouges had two more children and settled in Paris and Normandy, profiting from their celebrity with gifts and investments.[46] In 1390, Carrouges was promoted to a chevalier d'honneur as a bodyguard of the King, a title which came with a substantial financial stipend and was a position of important social standing. The following year he was dispatched to Hungary on a mission to investigate the severity of the threat from the Ottoman Empire, the boundaries of which had been steadily spreading under Sultan Bayezid I. In this mission he was second in command to Jean de Boucicaut, a Marshal of France and famous soldier, indicating the elevated social position Carrouges enjoyed following the duel.[47] In 1392, Carrouges was present for one of the more notorious occurrences in fourteenth-century France: the descent into madness of King Charles VI. As a chevalier d'honneur, Carrouges accompanied the King on the campaign and was present when the Royal Army entered Brittany to hunt for Pierre de Craon, a noble who had fled Paris after a failed attempt to murder Olivier V de Clisson, Constable of France.[48] As the army passed Le Mans on 8 August 1392, a loud noise startled the French King who, believing himself to be under attack, lashed out at the nearest person to him. The man was his brother Louis of Valois, who turned and fled. Killing several pages who attempted to calm his temper, the King set off on the full pursuit of Louis, leaving the army strung out across the countryside behind him. The pursuit continued for hours until the exhausted King was eventually subdued by his bodyguards, including Carrouges.[49] Crusade of Nicopolis In early 1396, following the peace treaty with England, the French army mobilised against another pressing threat; that of the Ottoman Turks to the East, as part of a new crusade. As a leader of the original party to investigate events in Hungary, it was natural that Jean de Carrouges would return with his followers in the service of his old commander, Admiral Jean de Vienne.[50] The army crossed Central Europe, united with the Hungarians and marched south, burning the city of Vidin, and massacring the inhabitants before following the course of the Danube southeast, cutting a swathe of destruction through the Ottoman territory. On 12 September, the army arrived at the city of Nicopolis, but was repulsed from its walls, and settled into a siege.[51] Two weeks later, Sultan Bayezid I arrived with a large army to the south of the town, and took up a strong defensive position, challenging the crusaders to meet him. The crusader army moved to confront him on 24 September, but poor discipline and fractured leadership between the national factions resulted in a premature assault by the French force against the bluffs controlled by Ottoman troops. With the allied army strung out, Bayezid marshaled his reserves, and defeated the crusaders in a furious engagement which felled most of the allied army.[51] Thousands more were captured and executed after the battle by the victorious Turkish troops. The exact fate of Sir Jean de Carrouges is unknown, but it is probable that he fell close to his commander, Jean de Vienne, whose forces were trapped in a gully and decimated by Turkish cavalry.[52] After his death, his estates passed to his 10-year-old son, Robert de Carrouges, and a mural of Jean and Marguerite de Carrouges was painted in the Abbey of St. Étienne in Caen to celebrate his memory. Over time, both the family and mural faded into obscurity.[53] His family was succeeded by that of Le Veneur de Tillières. The latter received the land and Château de Carrouges, which they remained the owner of until 1936, when the last representative of the family line ceded them to the State. In 1944, the castle was restored, as well as now managed by the Centre des monuments nationaux, and open to the public. The commune of Sainte-Marguerite-de-Carrouges, close to the town of Carrouges, was also named for Marguerite de Carrouges. LegacyDue to the celebrity and controversy surrounding the case, the judicial duel between Carrouges and Le Gris was one of the last permitted by the French government. As a well-attended and infamous event, it soon became a well-known case.[20] In France, the memory of the duel far outlasted its participants, primarily a result of it being recorded soon after by the contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart. Over the following century, vivid and imaginative accounts were carried in the chronicles of Jean Juvénal des Ursins and the Grandes Chroniques de France, as well as by Jehan de Waurin and others, many embellishing the story with imaginative twists.[54] The factual details of the case are unusually well-recorded for a medieval trial, as the records of the Parlement de Paris have survived intact, and Jacques Le Gris' lawyer Jean Le Coq kept meticulous notes on the case, which still exist. In addition to a clear view of proceedings, these notes also contain Le Coq's own concerns about his client, whose innocence Le Coq deemed highly suspect, according to The Last Duel author Eric Jager.[55]

Despite the well-recorded details, several chronicles including the Chronique du Religieux de Saint-Denys and the chronicles of Jean Juvénal des Ursins tell of a third man confessing to the rape at his death.[6] This story, which The Last Duel author Eric Jager claims is "without basis", was subsequently repeated in many later sources, particularly as proof for the great miscarriage of justice of the event and the tradition of trial-by-combat. Jager also claims that the Encyclopædia Britannica still contained a version of that false tale, under the entry for "Duel",[56] until the 1970s.[57] Other sources have discussed the story in varying degrees of detail, including a section in Diderot's Encyclopédie, in the Histoire du Parlement de Paris by Voltaire, and in a number of books written in the 19th century, including a work in the 1880s by a descendant of Jacques Le Gris, in which the author attempted to prove his ancestor's innocence.[58] In the 20th century, other authors have studied the case, the most recent being in the book The Last Duel: A True Story of Trial by Combat in Medieval France in 2004, by Eric Jager, a professor of English Literature at UCLA.[59] Jager's book, The Last Duel, was adapted by Ben Affleck, Nicole Holofcener and Matt Damon into the screenplay for the 2021 film adaptation The Last Duel. Damon and Affleck were also cast in the roles of Jean de Carrouges (Damon) and Pierre d'Alençon (Affleck), with Jodie Comer starring as Marguerite de Thibouville, and Adam Driver as Jacques le Gris, with Ridley Scott directing.[60][61] De Carrouges's duel is sometimes presented as the last of the French authorised duels, which is incorrect. The last duel[1] to be publicly authorised took place on 10 July 1547 at the castle of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It opposed Guy Chabot de Jarnac against François de Vivonne, following a request from Jarnac to King Henry II for regaining his honour. The duel was won by Jarnac[62] after injuring Vivonne with his sword; Vivonne later died of his wounds. Notes

ReferencesPrimary sources

Secondary sources

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||