|

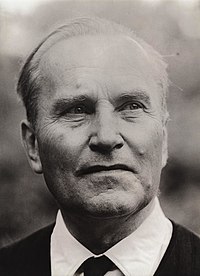

Jan Patočka

Jan Patočka (Czech pronunciation: [ˈpatot͡ʃka]; 1 June 1907 – 13 March 1977) was a Czech philosopher. Having studied in Prague, Paris, Berlin, and Freiburg, he was one of the last pupils of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. In Freiburg he also developed a lifelong philosophical friendship with Husserl's assistant Eugen Fink. Patočka worked in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic for almost his entire career, but never joined the Communist Party and was affected by persecution, which ended in his death as a dissident spokesperson of Charter 77. Patočka was a prolific writer and lecturer with a wide range of reference, contributing much to existential phenomenology as well as the interpretation of Czech culture and European culture in general. From his Czech collected works, some of the most notable have been translated to English and other major languages. These include the late works Plato and Europe (1973) and Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History (1975), in which Patočka developed a philosophy of history identifying the Socratic-Platonic theme of the care of the soul as the basis of "Europe". Early lifePatočka attended Jan Neruda Grammar School. In 1936 he completed his habilitation with a thesis entitled Přirozený svět jako filosofický problém (The natural world as a philosophical problem), the first systematic phenomenological study in the Czech language, which was correspondingly influential on Czech philosophy. In 1937, Patočka took over the post of editor-in-chief of the philosophical journal Česká mysl (The Czech Mind). In 1938 he became a member of the Institut International de Philosophie. WorksHis works mainly dealt with the problem of the original, given world (Lebenswelt), its structure and the human position in it. He tried to develop this Husserlian concept under the influence of some core Heideggerian themes (e.g. historicity, technicity, etc.) On the other hand, he also criticised Heideggerian philosophy for not dealing sufficiently with the basic structures of being-in-the-world, which are not truth-revealing activities (this led him to an appreciation of the work of Hannah Arendt). From this standpoint he formulated his own original theory of "three movements of human existence": 1) receiving, 2) reproduction, 3) transcendence. He also translated many of Hegel's and Schelling's works into Czech. In his lifetime, Patočka published in Czech, German, and French. Apart from his writing on the problem of the Lebenswelt, he wrote interpretations of Presocratic and classical Greek philosophy and several longer essays on the history of Greek ideas in the formation of our concept of Europe. Patočka increasingly focused on the idea of Europe during the 1970s.[1] As he was banned from teaching (see below), he held clandestine lectures in his private apartment on the Greek thought in general and on Plato in particular in the late 70s. These clandestine lectures are collectively known as Plato and Europe, and they are published under the same title in English. He also entered into discussions about modern Czech philosophy, art, history and politics. He was an esteemed scholar of Czech thinkers such as Komensky (b.1592) (also known as Comenius) and Masaryk (b.1850). In 1971, he has published a small treatise on Comenius in German titled Die Philosophy der Erziehung des J.A. Comenius (Comenius's Philosophy of Education). In 1977, his work on Masaryk culminated in 'Two Studies on Masaryk, which was initially a privately circulated typescript.[2] Patočka's Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History is analyzed at length and with much care in Jacques Derrida's important book The Gift of Death. Derrida was the most recent person who wrote or conversed with Patočka's thought; Paul Ricoeur and Roman Jakobson (who respectively wrote the preface and afterword to the French edition of the Heretical Essays) are two further examples.  During the years 1939–1945, when the Czech universities were closed, as well as between 1951 and 1968, and from 1972 on, Patočka was banned from teaching. Only a few of his books were published and most of his work circulated only in the form of typescripts kept by students and disseminated mostly after his death. Along with other banned intellectuals he gave lectures at the so-called "Underground University", which was an informal institution that tried to offer a free, uncensored cultural education. In January 1977 he became one of the original signatories and main spokespersons for the Charter 77 (Charta 77) human rights movement in Czechoslovakia. For the three months after the Charter was released he was intensely active writing and speaking about the meaning of the Charter, in spite of his deteriorating health. He was also interrogated by the police regarding his involvement with the Charter movement. On March 3, 1977, he was held by the police for ten hours, who had claimed that he would be allowed to speak in his role as a Charter spokesperson with a high-ranking official (in fact, this was a pretext to keep him from attending a reception at the West German embassy[3]). He fell ill that evening and was taken to the hospital, where his health briefly improved, enabling him to give one final interview with Die Zeit and to write one final essay entitled "What We Can Expect from Charter 77." On March 11 he relapsed, and on March 13 he died of apoplexy, at the age of 69. His brother František Patočka was a microbiologist. List of works

In English

MediaThe 2017 movie, The Socrates of Prague, was filmed in Prague and debuted in Brussels. This film explores Patočka's life and work in the second half of the twentieth century in Communist Central Europe by interviewing several of his students and friends.[4] References

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Jan Patočka. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||