|

Ion Creangă

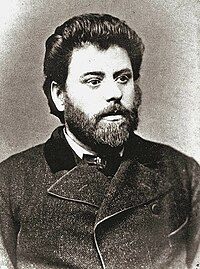

Ion Creangă (Romanian pronunciation: [iˈon ˈkre̯aŋɡə]; March 1, 1837 – December 31, 1889), also known as Nică al lui Ștefan a Petrei and Ioan Ștefănescu, was a Romanian writer, raconteur and schoolteacher. A main figure in 19th-century Romanian literature, he is best known for his Childhood Memories volume, his novellas and short stories, and his many anecdotes. Creangă's main contribution to fantasy and children's literature includes narratives structured around eponymous protagonists ("Harap Alb", "Ivan Turbincă", "Dănilă Prepeleac", "Stan Pățitul"), as well as fairy tales indebted to conventional forms ("The Story of the Pig", "The Goat and Her Three Kids", "The Mother with Three Daughters-in-Law", "The Old Man's Daughter and the Old Woman's Daughter"). Widely seen as masterpieces of the Romanian language and local humor, his writings occupy the middle ground between a collection of folkloric sources and an original contribution to a literary realism of rural inspiration. They are accompanied by a set of contributions to erotic literature, collectively known as his "corrosives". A defrocked Romanian Orthodox priest with an unconventional lifestyle, Creangă made an early impact as an innovative educator and textbook author, while pursuing a short career in nationalist politics with the Free and Independent Faction. His literary debut came late in life, closely following the start of his close friendship with Romania's national poet Mihai Eminescu and their common affiliation with the influential conservative literary society Junimea. Although viewed with reserve by many of his colleagues there, and primarily appreciated for his records of oral tradition, Creangă helped propagate the group's cultural guidelines in an accessible form. Later critics have often described him, alongside Eminescu, Ion Luca Caragiale and Ioan Slavici, as one of the most accomplished representatives of Junimist literature. Ion Creangă was posthumously granted several honors, and is commemorated by a number of institutions in both Romania and neighboring Moldova. These include the Bojdeuca building in Iași, which, in 1918, was opened as the first memorial house in Romania. His direct descendants include Horia Creangă, one of the leading Romanian architects during the interwar period. BiographyBackground and familyIon Creangă was born in Humulești in the Principality of Moldavia, a former village which has since been incorporated into Târgu Neamț city, the on of Orthodox trader Ștefan sin Petre Ciubotariul and his wife Smaranda.[1] His native area, bordering on heavily forested areas,[2] was in the Eastern Carpathian foothills, and included into what was then the Principality of Moldavia. The surrounding region's population preserved an archaic way of life, dominated by shepherding, textile manufacturing and related occupations,[3] and noted for preserving the older forms of local folklore.[4] Another characteristic of the area, which left an impression on Creangă's family history, was related to the practice of transhumance and the links between ethnic Romanian communities on both sides of the mountains, in Moldavia and Transylvania: on his maternal side, the writer descended from Maramureș-born peasants,[5] while, according to literary historian George Călinescu, his father's origin may have been further southwest, in Transylvania-proper.[2] The family had reached a significant position within their community: Ștefan sin Petre had made a steady income from his itinerant trade in wool, while his wife was the descendant of the Creangăs of Pipirig, a family of community leaders. The latter's members included Moldavian Metropolitan Iacob Stamati, as well as Smaranda's father, Vornic David, and her uncle Ciubuc Clopotarul, a monk at Neamț Monastery.[6] Proud of this tradition, she insisted that her son pursue a career in the Church.[7] According to his own recollection, the future writer was born on March 1, 1837—a date which has since been challenged.[6] Creangă's other statements mention March 2, 1837, or an unknown date in 1836.[8] The exactitude of other accounts is equally unreliable: community registers from the period gave the date of June 10, 1839, and mention another child of the same name being born to his parents on February 4, 1842 (the more probable birth date of Creangă's younger brother Zahei).[8] The imprecision also touches other aspects of his family life: noting the resulting conflicts in data, Călinescu decided that it was not possible for one to know if the writer's parents were married to each other (and, if so, if they were on their first marriage), nor how many children they had together.[8] At a time when family names were not legally required, and people were primarily known by various nicknames and patronymics, the boy was known to the community as Nică, a hypocorism formed from Ion, or more formally as Nică al lui Ștefan a Petrei ("Nică of Ștefan of Petru", occasionally Nic-a lui Ștefan a Petrei).[9] Childhood, youth and ordination After an idyllic period, which is recounted in the first section of his Childhood Memories, Ion Creangă was sent to primary school, an institution then in the care of Orthodox Church authorities, where he became noted for his rebellious attitude and appetite for truancy.[2] Among his colleagues was a female student, Smărăndița popii (known later as Smaranda Posea), for whom he developed an affection which lasted into his adult life, over decades in which the two no longer saw each other.[10] He was taught reading and writing in Cyrillic alphabet through peer tutoring techniques, before the overseeing teacher, Vasile a Ilioaiei, was lassoed off the street and conscripted by the Moldavian military at some point before 1848.[2] After another teacher, whom the Memories portray as a drunk, died from cholera in late 1848, David Creangă withdrew his grandson from the local school and took him to a similar establishment in Broșteni, handing him into the care of a middle-aged woman, Irinuca.[11] Ion Creangă spent several months at Irinuca's remote house on the Bistrița River, before the proximity of goats resulted in a scabies infection and his hastened departure for Pipirig, where he cured himself using birch extract, a folk remedy mastered by his maternal grandmother Nastasia.[2] After returning to school between late 1849 and early 1850, Creangă was pulled out by his financially struggling father, spent the following period working in wool-spinning, and became known by the occupational nickname Torcălău ("Spinster").[2] He only returned in third grade some four years later, having been sent to the Târgu Neamț public school, newly founded by Moldavian Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica as part of the Regulamentul Organic string of reforms.[2] A colleague of future philosopher Vasile Conta in the class of priest and theologian Isaia "Popa Duhu" Teodorescu, Creangă was sent to the Fălticeni seminary in 1854.[12] After having been registered as Ioan Ștefănescu (a variant of his given name and a family name based on his patronymic), the adolescent student eventually adopted his maternal surname of Creangă.[6] According to Călinescu, this was done either "for aesthetic reasons" (as his new name, literally meaning "branch" or "bough", "sounds good") or because of a likely discovery that Ștefan was not his real father.[6] Dan Grădinaru, a researcher of Creangă's work, believes that the writer had a special preference for the variant Ioan, generally used in more learned circles, instead of the variant Ion that was consecrated by his biographers.[10] Having witnessed, according to his own claim, the indifference and mundane preoccupations of his peers, Creangă admitted to having taken little care in his training, submitting to the drinking culture, playing practical jokes on his colleagues, and even shoplifting, while pursuing an affair with the daughter of a local priest.[8] According to his own statement, he was a philanderer who, early in his youth, had already "caught the scent" of the catrință (the skirt in traditional costumes).[13] In August 1855, circumstances again forced him to change schools: confronted with the closure of his Fălticeni school,[8] Creangă left for the Central Seminary attached to Socola Monastery, in Moldavia's capital of Iași.[14] Ștefan sin Petre's 1858 death left him without means of support, and he requested being directly ordained, but, not being of the necessary age, was instead handed a certificate to attest his school attendance.[8] He was soon after married, after a brief courtship, to the 15-year-old Ileana, daughter of Priest Ioan Grigoriu from the church of the Forty Saints, where he is believed to have been in training as a schoolteacher.[8] The ceremony took place in August 1859,[8] several months after the personal union between Moldavia and its southern neighbor Wallachia, effected by the election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as Domnitor. Having been employed as a cantor by his father in law's church, he was ordained in December of the same year, assigned to the position of deacon in Holy Trinity Church, and, in May 1860, returned to Forty Saints.[8] Relations between Creangă and Grigoriu were exceptionally tense. Only weeks after his wedding, the groom, who had probably agreed to marriage only because it could facilitate succeeding Grigoriu,[15] signed a complaint addressed to Metropolitan Sofronie Miclescu, denouncing his father in law as "a killer", claiming to have been mistreated by him and cheated out of his wife's dowry, and demanding to be allowed a divorce.[8] The response to this request was contrary to his wishes: he was ordered into isolation by the Dicasterie, the supreme ecclesiastical court, being allowed to go free only on promise to reconcile with Grigoriu.[8] Beginnings as schoolteacher and clash with the Orthodox Church In 1860, Creangă enlisted at the Faculty of Theology, part of the newly founded University of Iași,[8][15] and, in December 1860, fathered a son, Constantin.[8] His life still lacked in stability, and he decided to move out of Grigoriu's supervision and into Bărboi Church, before his position as deacon was cut out of the budget and his belongings were evicted out of his temporary lodging in 1864.[8] He contemplated leaving the city, and even officially requested a new assignment in the more remote Bolgrad.[8] Since January 1864, when the Faculty of Theology had been closed down,[15] he had been attending Iași's Trei Ierarhi Monastery normal school (Trisfetite or Trei Sfetite), where he first met the young cultural figure Titu Maiorescu, who served as his teacher and supervisor, and whence he graduated as the first in his class (June 1865).[15][16] Embittered by his own experience with the education system, Creangă became an enthusiastic promoter of Maiorescu's ideas on education reform and modernization, and in particular of the new methods of teaching reading and writing.[17] During and after completing normal school, he was assigned to teaching positions at Trisfetite.[18] While there, he earned the reputation of a demanding teacher (notably by accompanying his reports on individual students with characterizations such as "idiot", "impertinent" or "envious").[19] Accounts from the period state that he made use of corporal punishment in disciplining his pupils, and even surpassed the standards of violence accepted at the time.[10] In parallel, he was beginning his activities in support of education reform. By 1864, he and several others, among them schoolteacher V. Răceanu,[20] were working on a new primer, which saw print in 1868 under the title Metodă nouă de scriere și cetire pentru uzul clasei I primară ("A New Method of Writing and Reading for the Use of 1st Grade Primary Course Students"). It mainly addressed the issues posed by the new Romanian alphabetical standard, a Romanization replacing Cyrillic spelling (which had been officially discarded in 1862).[21] Largely based on Maiorescu's principles, Metodă nouă ... became one the period's most circulated textbooks.[21][22] In addition to didactic texts, it also featured Creangă's isolated debut in lyric poetry, with a naïve piece titled Păsărica în timpul iernii ("The Little Bird in Wintertime").[21] The book was followed in 1871 by another such work, published as Învățătoriul copiilor ("The Children's Teacher") and co-authored by V. Răceanu.[23] It included several prose fables and a sketch story, "Human Stupidity",[20] to which later editions added Poveste ("A Story") and Pâcală (a borrowing of the fictional folk character better known as Păcală).[24] In February 1866, having briefly served at Iași's Pantelimon Church, he was welcomed by hegumen Isaia Vicol Dioclias into the service of Golia Monastery.[8] Around 1867, his wife Ileana left him. After that moment, Creangă began losing interest in performing his duties in the clergy, and, while doing his best to hide that he was no longer living with his wife, took a mistress.[15] The marriage's breakup was later attributed by Creangă himself to Ileana's adulterous affair with a Golia monk,[25][26] and rumors spread that Ileana's lover was a high-ranking official, the protopope of Iași.[21] Creangă's accusations, Călinescu contends, are nevertheless dubious, because the deacon persisted in working for the same monastery after the alleged incident.[25]  By the second half of the 1860s, the future writer was also pursuing an interest in politics, which eventually led him to rally with the more nationalist group within the Romanian liberal current, known as Free and Independent Faction.[27][28] An agitator for his party, Creangă became commonly known under the nickname Popa Smântână ("Priest Sour Cream").[21][29] In April 1866, shortly after Domnitor Cuza was toppled by a coup, and just before Carol I was selected to replace him, the Romanian Army intervened to quell a separatist riot in Iași, instigated by Moldavian Metropolitan Calinic Miclescu. It is likely that Creangă shared the outlook of other Factionalists, according to which secession was preferable to Carol's rule, and was probably among the rioters.[30] At around the same time, he began circulating antisemitic tracts, and is said to have demanded that Christians boycott Jewish business.[10][31] He is thought to have coined the expression Nici un ac de la jidani ("Not even a needle from the kikes").[10] He was eventually selected as one of the Factionalist candidates for an Iași seat in the Romanian Deputies' Chamber, as documented by the memoirs of his conservative rival, Iacob Negruzzi.[32] The episode is supposed to have taken place at the earliest during the 1871 suffrage.[32] By 1868, Creangă's rebellious stance was irritating his hierarchical superiors, and, according to Călinescu, his consecutive actions show that he was "going out of his way for scandal".[19] He was initially punished for attending a Iași Theater performance, as well as for defiantly claiming that there was "nothing scandalous or demoralizing" in what he had seen,[15][19] and reportedly further antagonized the monks by firing a gun to scare off the rooks nesting on his church.[15][21][26][33] The latter incident, which some commentators believe fabricated by Creangă's detractors,[26] was judged absurd by the ecclesiastical authorities, who had been further alarmed by negative reporting in the press.[15][19][21] When told that no clergyman other than him had been seen using a gun, Creangă issued a reply deemed "Nasreddinesque" by George Călinescu, maintaining that, unlike others, he was not afraid of doing so.[19] Confronted by Metropolitan Calinic himself, Creangă allegedly argued that he could think of no other way to eliminate rooks, being eventually pardoned by the prelate when it was ruled that he had not infringed on canon law.[15] Defrocking and the Bojdeuca years Creangă eventually moved out of the monastery, but refused to relinquish his key to the church basement,[19] and, in what was probably a modernizing intent, chopped off his long hair, one of the traditional marks of an Orthodox priest.[15][26][34] The latter gesture scandalized his superiors, particularly since Creangă explained himself using an ancient provision of canon law, which stipulated that priests were not supposed to grow their hair long.[15][19] After some assessment, his superiors agreed not to regard this action as more than a minor disobedience.[15][19] He was temporarily suspended in practice but, citing an ambiguity in the decision (which could be read as a banishment in perpetuity), Creangă considered himself defrocked.[35] He relinquished his clerical clothing altogether and began wearing lay clothes everywhere, a matter which caused public outrage.[15] By then a teacher at the 1st School for Boys, on Română Street, Creangă was ordered out of his secular assignment in July 1872, when news of his status and attitude reached Education Minister Christian Tell.[15][26][34] Upset by the circumstances, and objecting in writing on grounds that it did not refer to his teaching abilities,[15][26] he fell back on income produced by a tobacconist's shop he had established shortly before being dismissed.[26][34] This stage marked a final development in Creangă's conflict with the church hierarchy. Summoned to explain why he was living the life of a shopkeeper, he responded in writing by showing his unwillingness to apologize, and indicated that he would only agree to face secular courts.[36] The virulent text notably accused the church officials of being his enemies on account of his "independence, sincerity, honesty" in supporting the cause of "human dignity".[37] After the gesture of defiance, the court recommended his defrocking, its decision being soon after confirmed by the synod.[26][36] In the meantime, Creangă moved into what he called Bojdeuca (or Bujdeuca, both being Moldavian regional speech for "tiny hut"), a small house located on the outskirts of Iași. Officially divorced in 1873,[15][38] he was living there with his lover Ecaterina "Tinca" Vartic.[21][38][39] A former laundress who had earlier leased one of the Bojdeuca rooms,[21] she shared Creangă's peasant-like existence. This lifestyle implied a number of eccentricities, such as the former deacon's practice of wearing loose shirts throughout summer and bathing in a natural pond.[40][41] His voracious appetite, called "proverbial gluttony" by George Călinescu,[19] was attested by contemporary accounts. These depict him consuming uninterrupted successions of whole meals on a daily basis.[19][21][41][42] In May 1874, soon after taking over Minister of Education in the Conservative Party cabinet of Lascăr Catargiu, his friend Maiorescu granted Creangă the position of schoolteacher in the Iași area of Păcurari.[15][43] During the same period, Ion Creangă met and became best friends with Mihai Eminescu, posthumously celebrated as Romania's national poet.[44] This is said to have taken place in summer 1875, when Eminescu was working as an inspector for Maiorescu's Education Ministry, overseeing schools in Iași County: reportedly, Eminescu was fascinated with Creangă's talents as a raconteur, while the latter admired Eminescu for his erudition.[45] Junimea reception At around the same time, Creangă also began attending Junimea, an upper class literary club presided upon by Maiorescu, whose cultural and political prestige was increasing. This event, literary historian Z. Ornea argued, followed a time of indecision: as a former Factionalist, Creangă was a natural adversary of the mainstream Junimist "cosmopolitan orientation", represented by both Maiorescu and Negruzzi, but was still fundamentally committed to Maiorescu's agenda in the field of education.[46] Literary historians Carmen-Maria Mecu and Nicolae Mecu also argue that, after attending Junimea, the author was able to assimilate some of its innovative teachings into his own style of pedagogy, and thus helped diffuse its message outside the purely academic environment.[47] The exact date of his reception is a mystery. According to Maiorescu's own recollections, written some decades after the event, Creangă was in attendance at a Junimea meeting of 1871, during which Gheorghe Costaforu proposed to transform the club into a political party.[48] The information was considered dubious by Z. Ornea, who argued that the episode may have been entirely invented by the Junimist leader, and noted that it contradicted both Negruzzi's accounts and minutes kept by A. D. Xenopol.[49] According to Ornea's assessment, with the exception of literary critic Vladimir Streinu, all of Creangă's biographers have come to dismiss Maiorescu's statement.[32] Several sources mention that the future writer was introduced to the society by Eminescu, who was an active member around 1875.[50] This and other details lead Ornea to conclude that membership was granted to Creangă only after the summer break of 1875.[51] Gradually[19] or instantly,[52] Creangă made a positive impression by confirming with the Junimist ideal of authenticity. He also became treasured for his talkative and jocular nature, self-effacing references to himself as a "peasant", and eventually his debut works, which became subjects of his own public readings.[53] His storytelling soon earned him dedicated spectators, who deemed Creangă's fictional universe a "sack of wonders"[19] at a time when the author himself had started casually using the pseudonym Ioan Vântură-Țară ("Ioan Gadabout").[54] Although still in his forties, the newcomer was also becoming colloquially known to his colleagues as Moș Creangă ("Old Man Creangă" or "Father Creangă"), which was a sign of respect and sympathy.[55] Among Ion Creangă's most dedicated promoters were Eminescu, his former political rival Iacob Negruzzi, Alexandru Lambrior and Vasile Pogor,[56] as well as the so-called caracudă (roughly, "small game") section, which comprised Junimists who rarely took the floor during public debates, and who were avid listeners of his literary productions[52] (it was to this latter gathering that Creangă later dedicated his erotic texts).[54] In parallel to his diversified literary contribution, the former priest himself became a noted voice in Junimist politics, and, like his new friend Eminescu, voiced support for the group's nationalist faction, in disagreement with the more cosmopolitan and aristocratic segment led by Maiorescu and Petre P. Carp.[57] By that the late 1870s, he was secretly redirecting political support from the former Factionalists to his new colleagues, as confirmed by an encrypted letter he addressed to Negruzzi in March 1877.[28] Literary consecrationAutumn 1875 is also often described as his actual debut in fiction prose, with "The Mother with Three Daughters-in-Law", a short story first publish in October by the club's magazine Convorbiri Literare.[21][58] In all, Convorbiri Literare would publish 15 works of fiction and the four existing parts of his Childhood Memories before Creangă's death.[59] Reportedly, the decision to begin writing down his stories had been the direct result of Eminescu's persuasion.[21][60] His talent for storytelling and its transformation into writing fascinated his new colleagues. Several among them, including poet Grigore Alexandrescu, tasked experimental psychologist Eduard Gruber with closely studying Creangă's methods, investigations which produced a report evidencing Creangă's laborious and physical approach to the creative process.[13] The latter also involved his frequent exchanges of ideas with Vartic, in whom he found his primary audience.[61] In addition to his fiction writing, the emerging author followed Maiorescu's suggestion and, in 1876, published a work of educational methodology and the phonemic orthography favored by Junimea: Povățuitoriu la cetire prin scriere după sistema fonetică ("Guide to Reading by Writing in the Phonetic System").[23] It was supposed to become a standard textbook for the training of teachers, but was withdrawn from circulation soon afterward, when the Catargiu cabinet fell.[62] After losing his job as school inspector following the decisions of a hostile National Liberal executive,[63] Mihai Eminescu spent much of his time in Bojdeuca, where he was looked after by the couple. For five months after quarreling with Samson Bodnărescu, his fellow poet and previous landlord, Eminescu even moved inside the house, where he reputedly pursued his discreet love affair with woman writer Veronica Micle, and completed as many as 22 of his poems.[21] Creangă introduced his younger friend to a circle of companions which included Zahei Creangă, who was by then a cantor, as well as Răceanu, priest Gheorghe Ienăchescu, and clerk Nicșoi (all of whom, Călinescu notes, had come to share the raconteur's lifestyle choices and his nationalist opinions).[64] Eminescu was especially attracted by their variant of simple life, the rudimentary setting of Creangă's house and the group's bohemian escapades.[21][65] Circumstances drew the two friends apart: by 1877, Eminescu had relocated in Bucharest, the capital city, regularly receiving letters in which Creangă was asking him to return.[21] He was however against Eminescu's plan to marry Veronica Micle, and made his objection known to the poet.[66] In 1879, as a sign that he was formalizing his own affair with Tinca Vartic, Creangă purchased the Bojdeuca in her name, paying his former landlord 40 florins in exchange.[21] That same year, he, Răceanu and Ienăchescu published the textbook Geografia județului Iași ("The Geography of Iași County"), followed soon after by a map of the same region, researched by Creangă and Răceanu.[20] A final work in the area of education followed in 1880, as a schoolteacher's version of Maiorescu's study of Romanian grammar, Regulile limbei române ("Rules of the Romanian Language").[20] Illness and death  By the 1880s, Creangă had epilepsy with accelerated and debilitating episodes.[67] He was also severely overweight, weighing some 120 kilograms (over 250 pounds), with a height of 1.85 meters (6 feet),[21] and being teasingly nicknamed Burduhănosul ("Tubby") by his friends[21][54] (although, according to testimonies by his son and daughter-in-law, he did not actually look his size).[10] Despite his activity being much reduced, he still kept himself informed about the polemics agitating Romania's cultural and political scene. He was also occasionally hosting Eminescu, witnessing his friend's struggle with mental disorder. The two failed to reconnect, and their relationship ended.[68] After one of the meetings, he recorded that the delusional poet was carrying around a revolver with which to fend off unknown attackers—among the first in a series of episodes which ended with Eminescu's psychiatric confinement and death during June 1889.[69] Around that time, Creangă, like other Junimists, was involved in a clash of ideas with the emerging Romanian socialist and atheistic group, rallied around Contemporanul magazine. This occurred after Contemporanul founder Ioan Nădejde publicly ridiculed Învățătoriul copiilor over its take on creationism, quoting its claim that "the invisible hand of God" was what made seeds grow into plants.[70] Creangă replied with a measure of irony, stating that "had God not pierced the skin over our eyes, we would be unable to see each other's mistakes".[70] Nevertheless, Călinescu argued, Nădejde's comments had shaken his adversary's religious sentiment, leading Creangă to question the immortality of the soul in a letter he addressed to one of his relatives in the clergy.[71] According to other assessments, he was himself an atheist, albeit intimately so.[10] In 1887, the National Liberal Ministry of Dimitrie Sturdza removed Creangă from his schoolteacher's post, and he subsequently left for Bucharest in order to petition for his pension rights.[72] Having hoped to be granted assistance by Maiorescu, he was disappointed when the Junimea leader would not respond to his request, and, during his final years, switched allegiance to the literary circle founded by Nicolae Beldiceanu (where he was introduced by Gruber).[72] Among Creangă's last works was a fourth and final part of his Memories, most likely written during 1888.[73] The book remained unfinished, as did the story Făt-frumos, fiul iepei ("Făt-Frumos, Son of the Mare").[59] He died after an epileptic crisis, on the last day of 1889,[74] his body being buried in Iași's Eternitatea Cemetery.[75] His funeral ceremony was attended by several of Iași's intellectuals (Vasile Burlă, A. C. Cuza, Dumitru Evolceanu, Nicolae Iorga and Artur Stavri among them).[76] WorkCultural contextThe impact of Ion Creangă's work within its cultural context was originally secured by Junimea. Seeking to revitalize Romanian literature by recovering authenticity, and reacting against those cultural imports it deemed excessive, the group notably encouraged individual creativity among peasants.[77] Reflecting back on Maiorescu's role in the process, George Călinescu wrote: "A literary salon where the personal merit would take the forefront did not exist [before Junimea] and, had Creangă been born two decades earlier, he would not have been able to present 'his peasant material' to anyone. Summoning the creativity of the peasant class and placing it in direct contact with the aristocrats is the work of Junimea."[77] His cogenerationist and fellow literary historian Tudor Vianu issued a similar verdict, commenting: "Junimea is itself ... an aristocratic society. Nevertheless, it is through Junimea that surfaced the first gesture of transmitting a literary direction to some writers of rural extraction: a phenomenon of great importance, the neglect of which would render unexplainable the entire subsequent development of our literature."[78] Also referring to cultural positioning within and outside the group, Carmen-Maria Mecu and Nicolae Mecu took the acceptance of "literate peasants" such as Creangă as exemplary proof of Junimist "diversity" and "tolerance".[79] Maiorescu is known to have had much appreciation for Creangă and other writers of peasant origin, such as Ion Popovici-Bănățeanu and Ioan Slavici.[80] Late in life, he used this connection to challenge accusations of Junimist elitism in the face of criticism from more populist traditionalists.[81] Nonetheless, Junimea members in general found Creangă more of an entertainer rather than a serious writer, and treasured him only to the measure where he illustrated their theories about the validity of rural literature as a source of inspiration for cultured authors.[41][82] Therefore, Iacob Negruzzi sympathetically but controversially referred to his friend as "a primitive and uncouth talent".[83] Maiorescu's critical texts also provide little individual coverage of Creangă's contributions, probably because these failed to comply exactly with his stratification of literary works into poporane ("popular", that is anonymous or collective) and otherwise.[84] Tudor Vianu's theory defines Creangă as a prime representative of the "popular realism" guidelines (as sporadically recommended by the Junimist doyen himself), cautioning however that Creangă's example was never mentioned in such a context by Maiorescu personally.[85] Although he occasionally downplayed his own contribution to literature,[21][41] Creangă himself was aware that his texts went beyond records of popular tradition, and made significant efforts to be recognized as an original author (by corresponding with fellow writers and willingly submitting his books to critical scrutiny).[41] Vianu commented at length on the exact relationship between the narrative borrowed from oral tradition and Creangă's "somewhat surreptitious" method of blending his own style into the folkloric standard, likening it to the historical process whereby local painters improvised over the strict canons of Byzantine art.[86] Creangă's complex take on individuality and the art of writing was attested by his own foreword to an edition of his collected stories, in which he addressed the reader directly: "You may have read many stupid things since you were put on this Earth. Please read these as well, and where it should be that they don't agree with you, take hold of a pen and come up with something better, for this is all I could see myself doing and did."[41] An exception among Junimea promoters was Eminescu, himself noted for expressing a dissenting social perspective which only partly mirrored Maiorescu's take on conservatism. According to historian Lucian Boia, the "authentic Moldavian peasant" that was Creangă also complemented Eminescu's own "more metaphysical" peasanthood.[87] Similarly, Z. Ornea notes that the poet used Creangă's positions to illustrate his own ethnonationalist take on Romanian culture, and in particular his claim that rural authenticity lay hidden by a "superimposed stratum" of urbanized ethnic minorities.[88] 20th century critics have described Creangă as one of his generation's most accomplished figures, and a leading exponent of Junimist literature. This verdict is found in several of Vianu's texts, which uphold Creangă as a great exponent of his generation's literature, comparable to fellow Junimea members Eminescu, Slavici and Ion Luca Caragiale.[89] This view complements George Călinescu's definition, placing the Moldavian author in the company of Slavici and Caragiale as one of the "great prose writers" of the 1880s.[90] Lucian Boia, who noted that "the triad of Romanian classics" includes Creangă alongside Eminescu and Caragiale, also cautioned that, compared to the other two (with whom "the Romanians have said almost all there is to say about themselves"), Creangă has "a rather more limited register".[87] The frequent comparison between Creangă and Caragiale in particular is seen by Vianu as stemming from both their common "wide-ranging stylistic means" and their complementary positions in relations to two superimposed phenomenons, with Caragiale's depiction of the petite bourgeoisie as the rough equivalent of Creangă's interest in the peasantry.[91] The same parallelism is explained by Ornea as a consequence of the two authors' social outlook: "[Their works] have cemented aesthetically the portrayal of two worlds. Creangă's is the peasant world, Caragiale's the suburban and urban one. Two worlds which represent, in fact, two characteristic steps and two sociopolitical models in the evolution of Romanian structures which ... were confronting themselves in a process that would later prove decisive."[92] According to the same commentator, the two plus Eminescu are their generation's great writers, with Slavici as one "in their immediate succession."[93] While listing what he believes are elements bridging the works of Creangă and Caragiale, other critics have described as strange the fact that the two never appear to have mentioned each other, and stressed that, although not unlikely, a direct encounter between them was never recorded in sources.[10] Narrative style and languageHighlighting Ion Creangă's recourse to the particularities of Moldavian regionalisms and archaisms, their accumulation making Creangă's work very difficult to translate,[94] George Călinescu reacted against claims that the narratives reflected antiquating patterns. He concluded that, in effect, Creangă's written language was the equivalent of a "glossological museum", and even contrasted by the writer's more modern everyday parlance.[64] Also discussing the impression that Creangă's work should be read with a Moldavian accent, noted for its "softness of sound" in relation to standard Romanian phonology, Călinescu cautioned against interpretative exaggerations, maintaining that the actual texts only offer faint suggestions of regional pronunciation.[95] Contrasting Creangă with the traditions of literature produced by Wallachians in what became the standard literary language, Călinescu also argued in favor of a difference in mentality: the "balance" evidenced by Moldavian speech and illustrated in Ion Creangă's writings is contrasted by the "discoloration and roughness" of "Wallachianism".[96] He also criticized those views according to which Creangă's variant of the literary language was "beautiful", since it failed to "please everyone on account of some acoustical beauty", and since readers from outside the writer's native area could confront it "with some irritation."[97] For Călinescu, the result nevertheless displays "an enormous capacity of authentic speech", also found in the works of Caragiale and, in the 20th century, Mihail Sadoveanu.[98] According to the same commentator, the dialectical interventions formed a background to a lively vocabulary, a "hermetic" type of "argot", which contained "hilarious double entendres and indecent onomatopoeia", passing from "erudite beauty" to "obscene laughter".[99] Some of the expressions characteristic of Creangă's style are obscure in meaning, and some other, such as "drought made the snake scream inside the frog's mouth", appear to be spontaneous and nonsensical.[13] Another specific trait of this language, commented upon by Vianu's and compared by him to the aesthetics of Classicism, sees much of Creangă's prose being set to a discreet poetic meter.[100] The recourse to oral literature schemes made it into his writings, where it became a defining trait. As part of this process, Călinescu assessed, "Creangă acts as all his characters in turn, for his stories are almost entirely spoken. ... When Creangă recounts, the composition is not extraordinary, but once his heroes begin talking, their gesticulation and wording reach a height in typical storytelling."[101] According to the critic, discovering this "fundamental" notion about Creangă's work was the merit of literary historian and Viața Românească editor Garabet Ibrăileanu, who had mentioned it as a main proof of affiliation to realism.[102] The distinctive manner of characterization through "realistic dialogues" is seen by Vianu as a highly personal intervention and indicator of the Moldavian writer's originality.[103] Both Vianu and Călinescu discussed this trait, together with the technique of imparting subjective narration in-between characters' replies, as creating other meeting points between Creangă and his counterpart Caragiale.[104] Partly replicating in paper the essence of social gatherings, Ion Creangă often tried to transpose the particular effects of oral storytelling into writing. Among these characteristic touches were interrogations addressed to the readers as imaginary listeners, and pausing for effect with the visual aid of ellipsis.[105] He also often interrupted his narratives with concise illustrations of his point, often in verse form, and usually introduced by vorba ceea (an expression literally meaning "that word", but covering the sense of "as word goes around").[106] One example of this connects the notions of abundance and personal satisfaction:

In other cases, the short riddles relate to larger themes, such as divine justification for one's apparent fortune: