|

Impeachment trial of Bill Clinton

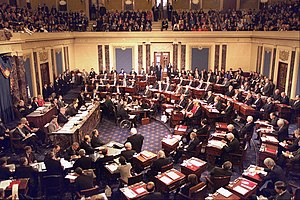

The impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, the 42nd president of the United States, began in the U.S. Senate on January 7, 1999, and concluded with his acquittal on February 12. After an inquiry between October and December 1998, President Clinton was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives on December 19, 1998; the articles of impeachment charged him with perjury and obstruction of justice. It was the second impeachment trial of a U.S. president, preceded by that of Andrew Johnson. The charges for which Clinton was impeached stemmed from a sexual harassment lawsuit filed against Clinton by Paula Jones. During pre-trial discovery in the lawsuit, Clinton gave testimony denying that he had engaged in a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. The catalyst for the president's impeachment was the Starr Report, a September 1998 report prepared by Ken Starr, Independent Counsel, for the House Judiciary Committee. The Starr Report included details outlining a sexual relationship between Clinton and Lewinsky.[1] Clinton was acquitted on both articles of impeachment, with neither receiving the two-thirds majority needed for a conviction, and remained in office. BackgroundUnder the U.S. Constitution, the House has the sole power of impeachment (Article I, Section 2, Clause 5), and after that action has been taken, the Senate has the sole power to hold the trial for all impeachments (Article I, Section 3, Clause 6). Clinton was the second U.S. president to face a Senate impeachment trial, after Andrew Johnson.[2] An impeachment inquiry was opened into Clinton on October 8, 1998. He was formally impeached by the House on two charges (perjury and obstruction of justice) on December 19, 1998.[3] The specific charges against Clinton were lying under oath and obstruction of justice. These charges stemmed from a sexual harassment lawsuit filed against Clinton by Paula Jones and from Clinton's testimony denying that he had engaged in a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. The catalyst for the president's impeachment was the Starr Report, a September 1998 report prepared by Independent Counsel Ken Starr for the House Judiciary Committee.[4] Planning for the trialBetween December 20 and January 5, Republican and Democratic Senate leaders negotiated about the pending trial.[5] Disagreement arose as to whether to call witnesses. This decision would ultimately not be made until after the opening arguments from the House impeachment managers and the White House defense team.[5] On January 5, Majority Leader Trent Lott, a Republican, announced that the trial would start on January 7.[5] There was some discussion about the possibility of censuring Clinton instead of holding a trial.[5] This was an idea that had been championed by Republican retired former Senate majority leader Bob Dole (who had been Clinton's Republican opponent in the 1996 United States presidential election), and which some Senate Democrats to embraced as an alternative to an impeachment trial.[6][7] Dole's own specific idea for how a censure would look was to have a censure passed and have Clinton then sign it himself in the presence of congressional leaders, the Vice President, Cabinet members, and the justices of the Supreme Court.[8] Officers of the trialPresiding officer The chief justice of the United States is cited in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 of the United States Constitution as the presiding officer in an impeachment trial of the President.[9] As such, Chief Justice William Rehnquist assumed that role. Rehnquist was a passive presiding officer, once commenting on his service as presiding officer of the trial, "I did nothing in particular, and I did it very well."[10] Rehnquist won praise from senators and from legal analysts for being a neutral-acting presiding officer.[11] On matter which Rehnquist did make a ruling on as presiding officer was to urge those arguing before the senate to refrain from referring to the senators as being a "jury". Senator Tom Harkin had objected to the use of the term "jurors". Agreeing with Harkin's position over the counter-position presented by the House impeachment managers (prosecutors), Rehnquist ruled, "The chair is of the view that the senator from Iowa's objection is well taken, that the core - the Senate is not simply a jury. It is a court in this case. And therefore, counsel should refrain from referring to the senators as jurors."[12][11] This indicated a belief that the senators collectively take on a role that is perhaps more akin to a judge than to a jury.[13] In 1992, Rehnquist had authored Grand Inquests, a book that had analyzed both the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and the impeachment of Samuel Chase.[14] House managersThirteen House Republicans from the House Judiciary Committee served as "managers", the equivalent of prosecutors.[15] They were designated to be the House impeachment managers the same day that the two articles of impeachment were approved (December 19, 1998).[5] They were named by a House resolution which was approved by a vote of 228–190.[16][17] On January 6, 1999 (the opening day of the 106th Congress) the House voted to 223–198 re-appoint the impeachment managers.[18]

Clinton's counsel

Pretrial The Senate trial began on January 7, 1999. Chair of the House impeachment manager team Henry Hyde led a procession of the House impeachment managers carrying the articles of impeachment across the Capitol Rotunda into the Senate chamber, where Hyde then read the articles aloud.[5] Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court William Rehnquist, who would preside over the trial, then was escorted into the chamber by senators by a bipartisan escort committee consisting of Robert Byrd, Orrin Hatch, Patrick Leahy, Barbara Mikulski, Olympia Snowe, Ted Stevens.[21] Rehnquist then swore-in the senators.[21] On January 8, during a closed-door meeting, the Senate unanimously passed a resolution on rules and procedure for the trial.[5][22][23] However, senators tabled the question of whether to call witnesses in the trial.[5] The resolution allotted the House impeachment managers and the president's defense team, each, 24 hours, spread out over several days, to present their cases.[5] It also allotted senators 16 hours to present questions to both the house impeachment managers and the president's defense team. After this, the senate would be able to hold a vote on whether to dismiss the case or to continue with it and call witnesses.[5] The trial remained in recess while briefs were filed by the House (on January 11) and Clinton (on January 13).[24][25] Additionally, on January 11, Clinton's defense team denied the charges made against Clinton in a thirteen page response to a Senate summons.[5] On January 13, the same day that his lawyers filed their pretrial brief, Clinton told reporters that he wanted to focus on the business of the nation rather than the trial, remarking, "They have their job to do in the Senate, and I have mine."[5] Testimony and deliberationsImpeachment managers' presentation (January 14–16)  The managers presented their case over three days, from January 14 to 16.[5] They justified removal of the President from office by virtue of "willful, premeditated, deliberate corruption of the nation's system of justice through perjury and obstruction of justice".[26] Among the evidence and illustrative tools utilized to illustrate their case were video clips of Clinton's grand jury testimony, charts, and quotes from the written record.[27] In the opening remarks, Hyde highlighted a need for jurors to be impartial in their judgement, remarking, "You are seated in this historic chamber ... to listen to the evidence as those who must sit in judgment. To guide you in this grave duty, you've taken an oath of impartiality."[26] Defense's presentation (January 19–21)  The defense's presentation took place January 19–21.[5][26] Clinton's defense counsel argued, "The House Republicans' case ends as it began, an unsubstantiated, circumstantial case that does not meet the constitutional standard to remove the President from office".[26] Questioning by members of the Senate (January 22–23)January 22 and 23 were devoted to questions from members of the Senate to the House managers and Clinton's defense counsel. Under the rules, all questions (over 150) were to be written down and given to Rehnquist to read to the party being questioned.[5][28][29] House impeachment managers' interview of Monica Lewinsky (January 24) On January 23, a judge had ordered Monica Lewinsky, who Clinton had allegedly perjured about a sexual relation with, to cooperate with the House impeachment managers, forcing her to travel from California back to Washington, D.C.[5] On January 24, she submitted to a nearly two-hour interview with the House impeachment managers, who remarked after the interview that Lewinsky was "impressive", "personable", and "would be a very helpful witness" if called.[5] Lewinsky's own lawyers claimed that no new information had been produced in the interview.[5] Debate and votes on motion to dismiss and motion to call witnesses (January 25–27)On January 25, Senator Robert Byrd (a Democrat) moved for dismissals of both articles of impeachment.[30][31] This motion would only require a majority vote to pass.[32] That day, senators heard arguments from the managers against dismissal, and from the president's defense team in support of dismissal, before then deliberating behind closed-doors in a closed session.[5][28] On January 26, House impeachment manager Ed Bryant motioned to call witnesses to the trial, a question the Senate had avoided up to that point. He requested depositions from Monica Lewinsky, Clinton's friend Vernon Jordan, and White House aide Sidney Blumenthal.[5][33] The House impeachment managers presented arguments in favor of allowing witnesses, then the president's legal team presented arguments against allowing witnesses.[28] Democrat Tom Harkin motioned to suspend the rules and hold open debate, rather than closed debate, on the motion to allow witnesses. The senators voted 58–41 against Harkin's motion, with Democrat Barbara Mikulski being absent due to illness. The Senate, thus, voted to deliberate on the question in private session, rather than public session, and such private deliberation was held that day in a closed session.[34] On January 27, the Senate voted on both motions in public session; the motion to dismiss failed on a near-completely party-line vote of 56–44, while the motion to depose witnesses passed by the same margin. Russ Feingold was the only Democrat to vote with Republicans against dismissing the charges and in support of deposing witnesses.[5][35][36] DepositionsVotes on procedures for witnesses (January 28)On January 28, the Senate voted against motions to dismiss the charges against Clinton and to suppress videotaped depositions of the witnesses from public release, with Democratic Senator Russ Feingold again voting with Republicans against both motions. Absent from the chamber, and therefore unable to vote, were Republican Wayne Allard and Democrat Barbara Mikulski, the latter of whom was absent due to illness.[37][38][39] Taping of closed-door depositions (February 1–3)Over three days, February 1–3, House managers took videotaped closed-door depositions from Monica Lewinsky, Vernon Jordan, Sidney Blumenthal. Lewinsky was deposed on February 1, Jordan on February 2, and Blumenthal on February 3.[5][28][40] Motions on presentation of evidence (February 4)On February 4, the Senate voted 70–30 that excerpting the videotaped depositions would suffice as testimony, rather than calling live witnesses to appear at trial.[5] House impeachment managers had wanted to call Lewinsky to testify in-person.[5] Showing of excerpts from closed-door depositions (February 6)Excerpts of the videotaped depositions were played by the House impeachment managers to the Senate on February 6.[41] These included excerpts of Lewinsky discussing such topics as her affidavit in the Paula Jones case, the hiding of small gifts Clinton had given her, and his involvement in procurement of a job for Lewinsky.[41][42] The showing of video on large screens was seen as a large departure in the use of electronics by the Senate, which has often disallowed electronics to be utilized.[5] Closing arguments (February 8)On February 8, closing arguments were presented with each side allotted a three-hour time slot. On the President's behalf, Charles Ruff, counsel to Clinton declared:

Chief Prosecutor Henry Hyde countered:

Failed motion for unanimous consent to investigate possible perjury by Sidney Blumenthal (February 9)On February 9, Arlen Specter (a Republican) asked for unanimous consent for parties to take additional discovery, including additional testimony on oral deposition by Christopher Hitchens, Carol Blue, Scott Armstrong, and Sidney Blumenthal in order to investigate possible perjury by Blumenthal. Tom Daschle (a Democrat) voiced objection.[43] Closed door deliberations (February 9–12)On February 9, a motion to suspend the rules and conduct open deliberations, introduced by Trent Lott (a Republican) was defeated 59–41.[28][44] Lott then motioned to begin holding closed-door deliberations, which was approved 53–47.[28][45] Closed door deliberations lasted through February 12. Verdict   On February 12, the Senate emerged from its closed deliberations and voted on the articles of impeachment. A two-thirds vote, 67 votes, would have been necessary to convict on either charge and remove the President from office. The perjury charge was defeated with 45 votes for conviction and 55 against, and the obstruction of justice charge was defeated with 50 for conviction and 50 against.[46][47][48] Senator Arlen Specter voted "not proved"[a] for both charges,[49] which was considered by Chief Justice Rehnquist to constitute a vote of "not guilty". All 45 Democrats in the Senate voted "not guilty" on both charges, as did five Republicans; they were joined by five additional Republicans in voting "not guilty" on the perjury charge.[46][47][48]

Public opinion Per Pew Research Center polling, the impeachment process against Clinton was generally unpopular.[55] Polls conducted during 1998 and early 1999 showed that only about one-third of Americans supported Clinton's impeachment or conviction. However, one year later, when it was clear that impeachment would not lead to the ousting of the President, half of Americans said in a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll that they supported impeachment, 57% approved of the Senate's decision to keep him in office, and two-thirds of those polled said the impeachment was harmful to the country.[56] Subsequent eventsContempt of court citationIn April 1999, about two months after being acquitted by the Senate, Clinton was cited by federal District Judge Susan Webber Wright for civil contempt of court for his "willful failure" to obey her orders to testify truthfully in the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit. For this, Clinton was assessed a $90,000 fine and the matter was referred to the Arkansas Supreme Court to see if disciplinary action would be appropriate.[57] Regarding Clinton's January 17, 1998, deposition where he was placed under oath, Webber Wright wrote:

On the day before leaving office on January 20, 2001, Clinton, in what amounted to a plea bargain, agreed to a five-year suspension of his Arkansas law license and to pay a $25,000 fine as part of an agreement with independent counsel Robert Ray to end the investigation without the filing of any criminal charges for perjury or obstruction of justice.[58][59] Clinton was automatically suspended from the United States Supreme Court bar as a result of his law license suspension. However, as is customary, he was allowed 40 days to appeal the otherwise automatic disbarment. Clinton resigned from the Supreme Court bar during the 40-day appeals period.[60] Political ramificationsWhile Clinton's job approval rating rose during the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal and subsequent impeachment, his poll numbers with regard to questions of honesty, integrity and moral character declined.[61] As a result, "moral character" and "honesty" weighed heavily in the next presidential election. According to The Daily Princetonian, after the 2000 presidential election, "post-election polls found that, in the wake of Clinton-era scandals, the single most significant reason people voted for Bush was for his moral character."[62][63][64] According to an analysis of the election by Stanford University:

The Stanford analysis, however, presented different theories and mainly argued that Gore had lost because he decided to distance himself from Clinton during the campaign. The writers of it concluded:[65]

According to the America's Future Foundation:

Political commentators have argued that Gore's refusal to have Clinton campaign with him was a bigger liability to Gore than Clinton's scandals.[65][67][68][69][70] The 2000 U.S. Congressional election also saw the Democrats gain more seats in Congress.[71] As a result of this gain, control of the Senate was split 50–50 between both parties,[72] and Democrats would gain control over the Senate after Republican Senator Jim Jeffords defected from his party in early 2001 and agreed to caucus with the Democrats.[73] Al Gore reportedly confronted Clinton after the election, and "tried to explain that keeping Clinton under wraps [during the campaign] was a rational response to polls showing swing voters were still mad as hell over the Year of Monica". According to the AP, "during the one-on-one meeting at the White House, which lasted more than an hour, Gore used uncommonly blunt language to tell Clinton that his sex scandal and low personal approval ratings were a hurdle he could not surmount in his campaign ... [with] the core of the dispute was Clinton's lies to Gore and the nation about his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky."[74][75][76] Clinton, however, was unconvinced by Gore's argument and insisted to Gore that he would have won the election if he had embraced the administration and its good economic record.[74][75][76] Preservation of items related to the trialAs the first impeachment trial held since Johnson's in 1868, the proceedings were viewed to hold historic significance. With the help of the Senate sergeant at arms, Senate Curator Diane Skvarla kept track of many objects used during the trial and had them stored for historic posterity. These included pencils utilized for tallying votes; several admission tickets printed for the trial; as well furniture such as the podium and easels used by the House-appointed impeachment managers and the defense counsel, the chair in which Chief Justice Rehnquist sat, and the tables utilized by the impeachment managers and defense counsel. After the trial, Senate leadership gave the impeachment managers and Clinton's counsel the chairs that each had sat in during the trial as a souvenir of their involvement.[77] NotesReferences

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||