|

Hymns for the Amusement of Children

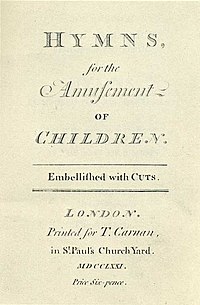

Hymns for the Amusement of Children (1771) was the final work completed by English poet Christopher Smart. It was completed while Smart was imprisoned for outstanding debt at the King's Bench Prison, and the work is his final exploration of religion. Although Smart spent a large portion of his life in and out of debt, he was unable to survive his time in the prison and died soon after completing the Hymns. Smart's Hymns are one of the first works of hymns dedicated to children, and they are intended to teach Christian virtues. Unlike some of the other works produced by Smart after his release from a mental asylum, such as A Song to David or Hymns and Spiritual Songs, this work was a success and went into many immediate editions. Part of the success of this work lies in the simplicity and accessibility of the text. However, Smart died before he ever saw the proceeds of the work and never learned of the book's success. Background Smart was released from asylum in 1763 and published two religious works, A Song to David and Hymn and Spiritual Songs, soon after. These were quickly attacked by critics that declared Smart was still "mad" and subsequently failed to become popular. Smart continued to work on religious works as he struggled to publish and support himself. However, he quickly fell into debt and, on 20 April 1770, he was arrested and sent to Debtors' prison.[1] On 11 January 1771 he was recommended to the King's Bench Prison.[2] Although he was in prison, Charles Burney purchased the "Rules" (allowing him some freedom) in order to help make Smart's final weeks peaceful although pathetic.[3] In his final letter, written to Rev. Mr. Jackson, Smart begged for three shillings in order to purchase food.[4] Soon after, on 20 May 1771, Smart died from either liver failure or pneumonia, after completing his final work, Hymns, for the Amusement of Children.[2] It is unknown how many poems published in the Hymns were written before Smart was imprisoned or during his final days, but at least one, titled "Against Despair" was produced during this time. A different version of the poem was published after his death in the Gentleman's Magazine. This version included a note claiming, "Extempore by the late C. Smart, in the King's-Bench," which verifies that he was writing hymns throughout this time, or, at least, editing them to create a better version.[5] Although five editions of the Hymns were published in the 18th century, only one edition was published before Smart died.[6] This edition was published by his brother-in-law, Thomas Carnan, and was announced in the Public Advertiser 27 December 1770. However, this edition did not list Smart as the author.[7] It is possible that there was a sixth edition of the Hymns, but that has since "disappeared"; there is also a possible pirated edition produced by Thomas Walker. Although the work made it as far as Boston, Massachusetts, as shown by an advertisement for selling the work in 1795, no Boston editions have been found, but such editions could exist in addition to the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania edition.[8] Smart's first children's hymn was "A Morning Hymn, for all the little good boys and girls" in the Lilliputian Magazine in 1751. During this time, there were only two models for him to base his children's hymns on: the works of Isaac Watts and of Charles Wesley. Watts's work attempted to amuse children while Wesley's attempted to simplify morality for them.[9] It is possible that Smart's Hymns were not modelled on Watts's or Wesley's actual hymns or songs, but instead after a note in Watts's work the Divine Songs which says:

The work was dedicated "to his Royal Highness Prince Frederick, Bishop of Osnabrug, these hymns, composed for his amusement, are, with all due Submission and Respect, humbly inscribed to him, as the best of Bishops, by his Royal Highness's Most Obedient and Devoted Servant, Christopher Smart."[11] Although the prince, the second son of King George III, was only seven at the time, Smart was given special permission to dedicate the work to the boy through the intervention with the royal family by either Richard Dalton or the King's Chaplain, William Mason.[12] Hymns for the Amusement of Children In essence, the Hymns for the Amusement of Children is intended to teach children the specific virtues that make up the subject matter of the work.[13] While trying to accomplish this goal, Smart emphasizes the joy of creation and Christ's sacrifice that allowed for future salvation. However, he didn't just try to spread joy, but structured his poems to treat valuable lessons about morality; his subjects begin with the three Theological Virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity), then the four Cardinal Virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and adds Mercy. The next six hymns deal with Christian duties and are followed by ten hymns on the Gospels. The final works introduce the miscellaneous Christian virtues that were necessary to complete Christopher's original self-proclaimed "plan to make good girls and boys."[14] All but three of the hymns were provided with a corresponding woodblock illustration. The original illustrations either represented the scene of the hymn or a symbolic representation of the hymn. However, later editions of the work sometimes included illustrations that did not match the corresponding hymn, which was the fault of "a general deterioration of standards in book production".[15] With such possibilities, it is hard to justify an exact relationship between any particular hymn and illustration.[16] There are thirty-nine hymns included in Hymns for the Amusement of Children:

Mirth Besides the hymns that are "expected" in a book of hymns, Arthur Sherbo points out that the collection contains hymns "on learning and on 'good-nature to animals'."[17] In particular, he emphasizes Hymn XXV "Mirth" as "showing anew the love for flowers that is a recurring characteristic of his poetry" as it reads:[17]

To Sherbo, this poem is "a good example of the artless quality" of the whole collection of Hymns.[17] Long-Suffering of God According to Moira Dearnley, Hymn XXIX "Long-Suffering of God" is "one of the more pathetic poems in Hymns for the Amusement of Children."[18] As a poem, it "restates Smart's certainty that the long-suffering God will eventually bestow his grace upon the barren human soul"[18] as it reads:

This final poem fittingly ends in "manic exultation" and shows "that for Smart, presentiments of the grace and mercy of God were inseparable from madness."[18] The Conclusion of the Matter Smart's final poem of the work, XXXIX "The Conclusion of the Matter", demonstrates to Neil Curry that the "joy and optimism of [Smart] are unwavering."[19] Smart "does not look back, he looks forward and the sequence ends on a note of triumph"[19] as it reads:

However, as Curry claims, "in this world Smart himself had won nothing."[19] Instead, Curry believes what Christopher Hunter stated about his uncle: "I trust he is now at peace; it was not his portion here."[19] Critical response Although he wrote his second set of hymns, Hymns for the Amusement of Children, for a younger audience, Smart cares more about emphasizing the need for children to be moral instead of "innocent".[20] These works have been seen as possibly too complicated for "amusement" because they employ ambiguities and complicated theological concepts.[21] In particular, Mark Booth questions "why, in this carefully polished writing.... are the lines sometimes relatively hard to read for their paraphrasable sense?"[22] Arthur Sherbo disagreed with this sentiment strongly and claims the Hymns "are more than mere hack work, tossed off with speed and indifference. They were written when Smart was in prison and despairing of rescue. Into these poems, some of them of a bare simplicity and naiveté that have few equals in literature of merit anywhere..."[17] However, he does admit some of the argument when he claims that "Generosity", along with a handful other hymns, was "not so simple and surely proved too much for the children for whom they were bought."[23] Not all critics agree that the work is too complex for children, and some, like Marcus Walsh and Karina Williamson, view that the works would have fit the appropriate level for children in the 18th century, especially with the short length of each hymn and a small illustration of the scene proceeding each one.[24] This is not to say that the works are "simple", because many words are complex, but, as Donald Davie explains, there is a "naiveté" in the work that allow them to be understood.[25] In particular, Moira Dearnley claims that the hymns contain a "high-spirited delight in the day-to-day life of children, the joy that characterizes the best the Hymns for the Amusement of Children."[26] See also

Notes

ReferencesWikisource has original text related to this article:

|