|

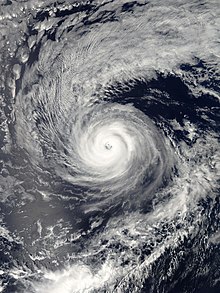

Hurricane Olivia (2018)

Hurricane Olivia was a tropical cyclone that impacted Hawaii as a weakening tropical storm in mid-September 2018, causing severe flooding and wind damage. Olivia was the first tropical cyclone to make landfall on Maui and Lanai in recorded history. It was the fifteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and sixth major hurricane of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season.[2][nb 1] A tropical depression formed southwest of Mexico on September 1, and slowly organized while hindered by northeasterly wind shear, strengthening into Tropical Storm Olivia a day later. Olivia began a period of rapid intensification on September 3, reaching its initial peak as a high-end Category 3 hurricane on September 5. Soon after, the cyclone began to weaken, before unexpectedly re-intensifying on September 6. Olivia peaked as a Category 4 hurricane on September 7, with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 951 mbar (28.08 inHg). Six hours later, Olivia began another weakening trend that resulted in the hurricane being downgraded to Category 1 status on September 8, east of the 140th meridian west. Olivia entered the Central Pacific Basin on September 9 while continuing to decay. For much of its existence, Olivia had tracked westward to northwestward under the influence of a subtropical ridge. The cyclone weakened to a tropical storm on September 12, while turning towards the west-southwest as a result of trade winds. Olivia made brief landfalls on Maui and Lanai, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), later in the day. Olivia fluctuated in intensity as it tracked away from the Hawaiian Islands, before transitioning to a post-tropical cyclone on September 14. It opened up into a trough of low-pressure several hours later. Olivia's approach towards the Hawaiian Islands prompted the issuance of tropical storm watches and warnings for Hawaii County, Maui County, the island of Oahu, and Kauai County. Hawaii Governor David Ige declared Hawaii, Maui, Kalawao, Kauai, and Honolulu counties disaster areas prior to Olivia's landfall in order to activate emergency disaster funds and management. Tropical-storm-force winds mainly affected Maui County and Oahu. Torrential rainfall occurred on both Maui and Oahu, peaking at 12.93 in (328 mm) in West Wailuaiki, Maui. Olivia felled trees, and caused thousands of power outages and severe flooding on Maui. Floodwaters deposited debris on roads and caused severe damage to portions of highways, most notably Lower Honoapiilani Road where cliffs were eroded along its shoulder; repairs to that road are still ongoing as of January 2021. In Honokohau Valley, the Honokohau stream rose over 15 ft (4.6 m), submerging a bridge and inundating over a dozen homes. Multiple homes and vehicles were swept away by floodwaters. Olivia left the valley without potable water for more than a week. Ditch systems in the valley that supply water to residents were damaged during the storm; repairs cost $300,000–$400,000 (2018 USD) and finished during May 2020. Several hundred power outages occurred on Molokai, and around 1,100 lost power in Honolulu. A pipe overflowed from excessive rainfall on Oahu, sending raw sewage into Kapalama Stream and Honolulu Harbor. United States President Donald Trump issued a disaster declaration for Hawaii to aid with emergency response efforts. Olivia caused a total of $25 million in damage throughout Hawaii. Meteorological history Map key Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h) Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h) Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h) Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h) Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h) Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h) Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h) Unknown Storm type Hurricane Olivia originated from a disturbance that developed over the southwest Caribbean Sea on August 26. The disturbance tracked westward, crossing over Central America and entering the Eastern Pacific Ocean a couple of days later. Associated thunderstorm activity increased over the next few days, and by early August 31, a broad low-pressure area had developed several hundred miles south of Mexico's southwestern coast. Atmospheric convection organized around the system's center, prompting the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to declare a tropical depression had formed by 00:00 UTC on September 1, approximately 405 mi (652 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico.[1] While the depression was located over warm sea surface temperatures, northeasterly wind shear prevented any intensification from occurring on September 1.[1][4] Although the system was still elongated and disorganized,[5] convection had been increasing over and west of its center. This led to the depression strengthening into Tropical Storm Olivia by 00:00 UTC on September 2, while it was located 520 mi (840 km) south of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.[1] Soon after, Olivia began a northwestward motion as a result of a weakness in the subtropical ridge located to the north.[1] Wind shear displaced the cyclone's low-level center to the north and northeast of the convective canopy through September 3.[6][7] The wind shear abated early on September 3, allowing Olivia to begin a period of rapid intensification. Meanwhile, the storm turned towards the west as the ridge strengthened.[1] Later in the day, the amount of banding features – significantly elongated, curved bands of rain clouds – increased greatly while Olivia's inner core strengthened;[8] microwave imagery displayed an irregular eye underneath the system's central dense overcast.[9] Olivia became a Category 1 hurricane around 00:00 UTC on September 4, while located 575 mi (925 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas. The cyclone continued to intensify, reaching its initial peak intensity as a Category 3 major hurricane at 00:00 UTC on September 5, with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h).[1] Around that time, Olivia exhibited a prominent 15–25 mi (24–40 km) wide eye within its central dense overcast.[10] The hurricane began to weaken shortly after its initial peak as sea surface temperatures decreased, wind shear increased, and dry air incorporated into the storm. Olivia's eyewall collapsed in the north and convection eroded in the northwestern quadrant.[1][11] Olivia bottomed out as a minimal Category 2 hurricane around 18:00 UTC on September 5. Models had predicted that Olivia would weaken as a result of dry air and lower sea surface temperatures, however, a second, unexpected round of intensification occurred.[12] At the time, the hurricane's eye was uneven and the convective canopy was lopsided. Olivia strengthened over the next day, regaining major hurricane status by 12:00 UTC on September 6. The cyclone peaked around 00:00 UTC on September 7, as a Category 4 hurricane with 1-minute maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 951 mbar (28.08 inHg), while located over 1,265 mi (2,036 km) west of Cabo San Lucas.[1] Olivia had become an annular hurricane, developing a cloud-free eye embedded within a symmetric, ring-shaped central dense overcast.[13] Cooler sea surface temperatures of 77–79 °F (25–26 °C) and low-to-mid-level dry air caused Olivia to weaken shortly after its peak.[1] Continuing to track west-northwestward under the subtropical ridge,[14] Olivia gradually weakened as it approached the Central Pacific Ocean, with cloud tops warming and its eye temperature decreasing.[15][16] Olivia began tracking westward under the influence of a strengthening subtropical ridge mid-day on September 8.[17] After having fallen to Category 1 status, the cyclone crossed the 140th meridian west and entered the Central Pacific Basin around 00:00 UTC on September 9.[1] Olivia continued to decay, with its eye disappearing, and the cyclone weakening to a minimal Category 1 storm by 12:00 UTC.[1][18] Later that day, low wind shear and slightly higher sea surface temperatures allowed Olivia to restrengthen slightly and re-develop an eye feature on satellite imagery. The hurricane strengthened to 85 mph (140 km/h) by 00:00 UTC on September 10 and maintained that intensity for 12 hours before increasing wind shear caused the storm to weaken once more. Olivia's eye became cloud-filled and the system fell below hurricane intensity by 06:00 UTC on September 11.[1] Increasing wind shear caused faster weakening, displacing convection well to the east of the low-level center.[19][20][21] Olivia weakened into a 45 mph (75 km/h) tropical storm by 06:00 UTC on September 12.[1] Flow from low-level trade winds had turned Olivia to the west-southwest and caused it to slow down by 00:00 UTC on that day. An upper-level trough shifted the storm back to a westward direction and further reduced its forward speed later that day.[1] Olivia made brief landfalls over Maui and Lanai, the first such instance in recorded history,[22] on September 12, at 19:10 UTC and 19:54 UTC, respectively, with sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). High wind shear and interaction with the mountainous terrain of the Hawaiian Islands led to the rapid depletion and displacement of convection away from Olivia's center.[1][23] Tracking west-southwestward, away from the Hawaiian Islands, Olivia weakened to tropical depression status by 06:00 UTC on September 13. Convection briefly redeveloped near the center of the depression, allowing Olivia to become a tropical storm again around 18:00 UTC. The storm turned westward and transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone by 06:00 UTC on September 14. This system opened up into a trough of low-pressure about 12 hours later.[1] Preparations Hurricane Olivia's approach towards the Hawaiian Islands warranted the issuance of tropical cyclone watches and warnings. A tropical storm watch was issued for the islands of Hawaii, Maui, Molokai, Lanai, Kahoolawe, and Oahu on September 10 at 03:00 UTC. By 15:00 UTC, every watch had been upgraded to a tropical storm warning except for the island of Oahu, which was upgraded at 03:00 UTC on the next day. Additional tropical storm watches had been issued for the islands of Kauai and Niihau at the same time on September 11. These watches were upgraded to tropical storm warnings by 21:00 UTC.[1] The United States Coast Guard initiated Condition Whiskey[nb 2] at 08:00 HST on September 8 for ports in Hawaii, Maui, and Honolulu counties, expecting gale-force winds to occur within 72 hours.[25] Honolulu and Kauai county ports were later upgraded to Condition X-ray, with the expectation of gale-force winds occurring within 48 hours. By 08:00 HST on September 9, ports in Hawaii and Maui counties were upgraded to Condition Yankee, with the expectation of gale-force winds within 24 hours. At both of these conditions, restrictions were set on ports. Pleasure craft were asked to travel into safer waters, and any barge or other ocean-traveling ship above 200 short tons (180 t) were asked to remain in port if they had permission to do so or depart from the port if they did not.[26] Ports in Hawaii, Maui, and Honolulu counties were upgraded to Condition Zulu at 08:00 HST on September 11, when gale-force winds were expected to occur in less than 12 hours. All ports in those counties were closed to naval traffic until the danger from Olivia had ended.[27] Maui County closed all government offices, schools, and the court system in anticipation of Olivia's impact. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) readied personnel and supplies on Maui, and the Hawaii National Guard stationed troops and transportation trucks on the eastern side of the island. Hawaiian Airlines canceled flights for its Ohana commuter airline service.[28] Fees for changing flights were waived by multiple airline companies during the storm.[29] Hawaii Governor David Ige requested federal help for search and rescue, medical evacuations, medical care and shelter commodities, and generators.[30] The governor declared Hawaii, Maui, Kalawao, Kauai, and Honolulu counties disaster areas prior to Olivia's landfall in order to activate emergency disaster funds and management.[31] Impact and aftermath Olivia brought heavy rainfall, winds, and high surf to the main Hawaiian Islands, less than a month after Hurricane Lane dropped a record 58 in (1,500 mm) of rain on the state.[32][33] From September 11–12, 8–20 ft (2.4–6.1 m) high surf was reported along the northern and eastern facing shores of the Big Island, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai. Surf of this magnitude occurred along the southern and eastern shores of Oahu, and Kauai.[34] In Maui County, the Lanai Airport recorded peak wind gusts of 55 mph (89 km/h).[35] The highest rainfall occurred near West Wailuaiki on the island of Maui, peaking at 12.93 in (328 mm). Around 10.31 in (262 mm) of rain was recorded at the Manoa Lyon Arboretum on Oahu.[36] A flash flood warning was issued for Molokai and Maui.[28][37] Olivia felled trees, caused severe flooding, and caused 6,800 power outages on Maui.[38] Rising rivers prompted the evacuation of several residences in Lahaina and another in the Waihee Valley.[37][39] In the former, floodwaters deposited mud in one home and fractured a concrete barrier wall along the property's riverfront boundary.[40] Around 65 reports of damage occurred on Maui, with some reaching complete and total destruction.[41] A brown water advisory, a recommendation for people to stay out of affected waters, was issued on September 18 for coastal waters near Waiheʻe to Kahului and Honokōhau to Honua Kai due to the possibility of contamination from various sources, including chemicals, sewage, pesticides, and animal carcasses. This replaced an advisory that covered the entire island of Maui; that advisory was issued after Olivia moved through the region.[42] Multiple parks and forest reserves were closed to visitors due to a combination of water damage, land erosion, and downed trees.[43] Several sections of the Hana Highway were closed after trees fell.[38] The Honolua Ditch was clogged with debris; authorities asked customers to conserve water for the remainder of September while the ditch was cleaned out and repaired. Floodwaters damaged multiple portions of Lower Honoapiilani Road and eroded cliffs along its shoulder; temporary repairs cost about $50,000 and complete repairs were estimated to exceed $100,000 in cost.[44][45] Temporary cliff restoration work was ongoing as of January 2021, consisting of sandbag and sheet wall repairs. Hololani Resort Condominiums and Goodfellow Bros, the company performing the work, was fined $75,000 in that month for violating state health and county environmental regulations.[46] In the Honokohau Valley, multiple buildings, cars, and trees were swept away by floodwaters. At least a dozen homes were flooded after debris clogged streams, forcing the strong currents to forge new paths.[43][47][48] The Honokohau stream rose 15 ft (4.6 m), submerging the Honokohau bridge; debris floating downstream struck the foundations of the bridge.[49] A bridge that provided access to a home was destroyed, resulting in $5,000 in damage. The house suffered flood damage; the telephone and water lines were destroyed. An elderly woman was rescued by her neighbors during the storm. The floor of a house was destroyed after it was submerged under 1 ft (0.30 m) of water. Another house had its floors plastered with mud after floodwaters entered the structure.[50] On one property, a home was swept away, and another was moved off its foundation by floodwaters; the latter and a third building both required demolition due to flood damage.[41][51] Another home was swept away by floodwaters and a second house was moved around 100 yd (91 m). Around a month after the storm, both homes were intentionally set on fire before repairs could commence; the fires caused a total of $80,000 in damage.[52] The valley was without potable water at least a week after the storm. Maui County workers parked a water tanker on the Honoapiilani Highway while work was underway on water services. Volunteers worked to clear the wreckage left by the storm so buildings could be repaired. The American Red Cross helped with recovery efforts.[50] Maui restaurants donated 100 meals to people affected by the storm and those volunteering to help clear the wreckage left behind.[48] The cost to replace a broken water inflow pipe in the valley was estimated at $100,000.[41][45] A road in Kahana that had been damaged during the storm was repaired for $100,000.[41] Torrential rainfall and flooding from Hurricanes Lane and Olivia reduced water flow and damaged a control gate in the Honokohau Stream ditch system. The ditch provided water to farmers as well as residential areas. The Ka Malu o Kahalawai and West Maui Preservation Association filed a complaint with the state water commission in spring 2019, alleging that the Maui Land & Pineapple Company was wasting water, causing water dearths, and not maintaining critical infrastructure. The state commission approved a motion on November 20, 2019, that The Maui Land & Pineapple Company must upgrade the damaged structures.[53] The Maui Land & Pineapple Company announced on December 4, 2019, that it began repairs on the Honokohau Stream ditch system.[54] The project cost around $300,000–$400,000, with repairs finishing on May 11, 2020.[53] Floodwaters made eastern Molokai's only highway impassable.[37][39] At least 700 power outages occurred on the island, resulting in the closure of a school.[43] Power was restored by September 12; crews fixed multiple areas of downed lines and damaged poles.[55] The storm caused around 1,140 power outages in Honolulu.[56] A roof was blown off a structure in ʻĀina Haina. Numerous roads, including portions of the Kamehameha Highway and Kalanianaole Highway, were closed due to flooding.[57] Rainfall from Olivia caused the waterlevel behind the earthen Nuʻuanu Dam #1 to rise 4–5 ft (1.2–1.5 m) overnight, prompting firefighters and officials to pump and siphon water away; however, the dam was not at risk of failure.[58][59][60][61] A pipe overflowed from excessive rainfall, sending over 32,000 US gal (120,000 L) of raw sewage into the Kapalama Stream and Honolulu Harbor; the city disinfected the waters.[58] At least 775 US gal (2,930 L) of sewage was contained by a vacuum truck.[57] A 100 ft (30 m) landslide occurred at the top of the Manoa Falls Trail around a week after the storm, taking down trees and boulders.[62] According to Aon, Olivia caused a total of US$25 million in damage throughout Hawaii.[63] United States President Donald Trump declared Hawaii a disaster area to improve the response of FEMA.[37] Bank of Hawaii allocated $25,000 to relief programs for the extension or forbearance of loans, necessary items, and home and vehicle repairs.[55] Hotel occupancy dropped an average of 2.1% in September for Maui compared to the same time in 2017 as a result of hurricanes Lane and Olivia.[64] Overall, tourism increased in the month of October despite the two storms.[65] See also

Notes

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Olivia (2018).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||