|

Hurricane Hermine

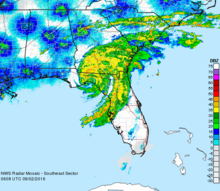

Hurricane Hermine (/hɛrˈmiːn/, her-MEEN)[1] was the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, and the first to develop in the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Ingrid in 2013. The ninth tropical depression, eighth named storm, and fourth hurricane of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season, Hermine developed in the Florida Straits on August 28 from a long-tracked tropical wave. The precursor system dropped heavy rainfall in portions of the Caribbean, especially the Dominican Republic and Cuba. In the former, the storm damaged more than 200 homes and displaced over 1,000 people. Although some areas of Cuba recorded more than 12 in (300 mm) of rain, the precipitation was generally beneficial due to a severe drought. After being designated on August 29, Hermine shifted northeastwards due to a trough over Georgia and steadily intensified into an 80 mph (130 km/h) Category 1 hurricane just before making landfall in the Florida Panhandle during September 2. After moving inland, Hermine quickly weakened and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 3 near the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The remnant system meandered offshore the Northeastern United States before dissipating over southeastern Massachusetts on September 8. In preparation of Hermine, multiple tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued in the Southeastern United States, while state of emergencies were declared in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey. Storm surge and heavy rainfall along the Florida Gulf Coast caused significant damage. In Citrus County, one of the worst areas impacted, 2,694 structures sustained damage, of which 531 suffered major damage, while damage reached about $102 million. Similar coastal and freshwater flooding occurred in Pasco County, where 7 homes were destroyed, 305 sustained major damage, and 1,564 received minor damage. Winds primarily left power outages and downed trees, some of which fell onto buildings and vehicles. About 325,000 people were left without electricity, including 80% of Tallahassee. One death occurred in the state after a tree fell on a homeless man's tent near Ocala. Flooding and fairly strong winds in other states such as Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina caused further damage, but to a lesser degree. One fatality each occurred in South Carolina and North Carolina. In New York, two fishermen drowned near the Wading River on Long Island due to rough surf. Overall, Hermine caused about $550 million (2016 USD) in damage in the United States. Meteorological history Map key Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h) Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h) Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h) Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h) Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h) Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h) Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h) Unknown Storm type A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa between late August 16 and early August 17.[2] On August 18, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first noted the tropical wave as a potential area for tropical cyclogenesis, associated with an area of disorganized convection about 300 mi (480 km) southwest of Cabo Verde. Environmental conditions were expected to be favorable for continued organization.[3] Dry and stable air was an initial inhibiting factor in development,[4] with deep convection waning on August 20 and August 21.[2] However, the convection and circulation had become better defined by August 21.[5] By August 23, the system had developed an elongated and poorly-defined circulation, as indicated by the Hurricane Hunters,[6] though convention continued to expand.[2] On the next day, the low pressure area crossed Guadeloupe into the Caribbean Sea while producing gale-force winds.[7][8] By this point, the NHC noted that the system could develop into a tropical depression at any time, as the system was only lacking a well-defined circulation.[9] Marginal wind shear disrupted the system's organization, and it passed north of Puerto Rico without further development,[10] with winds dropping below gale-force on August 25.[11] Initially, the system moved quickly westward with a forward speed averaging about 23 mph (37 km/h), but slowed down considerably after the northern portion of the wave split off on August 26.[2] The low pressure area crossed the southern Bahamas with scattered convection,[12] becoming more defined on August 27 while moving near the northern Cuban coast.[13] Wind shear prevented quicker development,[14] although conditions became more favorable closer to the Gulf of Mexico. On August 28, the convection increased and became more organized.[15] Later that day, the Hurricane Hunters observed a well-defined circulation.[16] Based on the observations and the convective organization, it is estimated that Tropical Depression Nine developed at 18:00 UTC on August 28 while situated about 60 mi (100 km) south-southeast of Key West, Florida.[2]  Deep convection increased further as the depression moved more into the Gulf of Mexico,[17] steered by a ridge over southern Florida,[18] although it remained ragged and displaced from the circulation.[19] Dry air to the system's west negated the otherwise favorable warm waters.[18] The depression failed to organize more on August 30 as the low- and mid-level circulations remained misaligned.[20] A large plume of convection developed over the system on August 31 as outflow improved and wind shear decreased.[21] Later that day, reports from the Hurricane Hunters indicated that the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Hermine about 395 mi (640 km) southwest of Apalachicola, Florida.[22] Late on August 31, Hermine began accelerating to the northeast, influenced by a developing mid-level trough over the southeastern United States.[23] Lessening shear and water temperatures around 86 °F (30 °C) allowed the storm to intensify.[24] Although outflow was restricted to the northwest, curved rainbands increased over the eastern half of the system,[25] increasing the extent of tropical storm-force winds.[26] Additionally, a ragged eye became visible on satellite imagery on September 1, and at 18:00 UTC, Hermine intensified into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[2] The hurricane strengthened slightly further to a peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h) by 00:00 UTC on September 2.[27] At around 05:30 UTC (1:30 a.m. EDT) that day, Hermine made landfall just east of St. Marks, Florida, at peak intensity, with a minimum pressure of 981 mbar (hPa; 29.00 inHg).[2] Hermine became the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Wilma on October 24, 2005.[28] Within four hours of landfall, the winds dropped below hurricane force as the appearance on radar imagery degraded.[29] The convection diminished while Hermine crossed into Georgia, with the strongest winds near the Atlantic coast.[30] The center elongated as it continued quickly northeastward ahead of the trough.[31] With the convection far ahead of the circulation, Hermine transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 12:00 UTC on September 3 as it emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the Outer Banks of North Carolina.[2] Dry air wrapped into the eastward-moving center,[32] while convection pulsed north of the former hurricane, possibly due to the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream.[33] By September 5, the system devolved into several rotating circulations as the overall system slowed and turned to the northwest, steered by a ridge to the north.[34] The convection began waning on the next day,[35] as the storm turned due westward.[36] At 18:00 UTC on September 6, the NHC ceased issuing advisories on the post-tropical cyclone as Hermine continued to weaken amid cooler waters and convective stability.[37] The remnants continued to meander offshore New Jersey and Long Island, eventually dissipating near Chatham, Massachusetts late on September 8.[2] Preparations On August 30, the NHC began issuing tropical cyclone warnings and watches for the Florida Gulf Coast. By the time Hermine reached hurricane status, a hurricane warning was in place from the mouth of the Suwannee River to Mexico Beach. A tropical storm warning extended southward to Englewood, which included the Tampa Bay Area, and westward to the Walton–Bay county line. A hurricane watch was also in effect from the mouths of the Suwannee and Anclote rivers. On August 31, a tropical storm watch was added for the Atlantic coast between Marineland, Florida, to the Altamaha Sound in Georgia. As Hermine approached and moved up the coast, tropical storm warnings were in place as far south as Marineland, and as far northeast as Sagamore Beach, Massachusetts, including portions of the Tidal Potomac River, the Chesapeake and Delaware bays, Long Island Sound, New York City, Block Island, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and Cape Cod. All tropical storm warnings were dropped when the NHC discontinued advisories at 18:00 UTC on September 6.[2] Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency for 51 counties.[38] In response to the then-developing storm, early voting for the primary election on August 30 was extended by one day in Bradford, Broward, Charlotte, Duval, Hillsborough, Miami-Dade, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach. and Pinellas counties.[39] In six counties, school was canceled on September 1 and 2, while twenty-nine other counties had no school on September 2.[38][40] Mandatory evacuations were ordered for portions of Dixie, Franklin, Taylor, and Wakulla counties.[38] States of emergencies were declared in Georgia,[28] North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey due to the storm.[41] Hermine affected the east coast of the United States during the busy Labor Day weekend, causing many beaches to be closed in Delaware, New Jersey, and New York.[41] Amtrak canceled or altered train lines due to the threat from the storm.[28] In Savannah, Georgia, Bacon Fest was cancelled, and a beer fest was moved indoors.[42] In Charleston, South Carolina, the city government provided 3,000 sandbags to residents, preparing less than a year after damaging floods hit the state. Outer Banks ferry service was cancelled[43] and bridges in Dare County, North Carolina, were closed due to the high winds. Officials deployed or readied swift water teams, helicopters, and the North Carolina National Guard in the eastern portion of the state. The Virginia National Guard utilized 270 members to help prepare for the storm's potential flooding and power outages.[43] A Bruce Springsteen concert in Virginia Beach, Virginia, was postponed two days,[41] and several performances for the town's American Music Festival were cancelled or moved indoors.[44] ImpactCaribbeanOn Antigua, a lightning strike produced by thunderstorms associated with the precursor tropical wave severely damaged two 69 kV transmission lines, causing an island-wide blackout on August 24.[45] Some locations in Puerto Rico observed 3 to 5 in (76 to 127 mm) of rainfall,[46] causing flooding, especially in the Ponce area. Primarily, streets were inundated with water, though at least one house was flooded.[47] In the Dominican Republic, some areas received nearly 4 in (100 mm) of rain on August 25 alone from Hermine's precursor. In 19 provinces, residents and authorities were on alert due to rapidly rising rivers and expectations of flooding.[48] Throughout the country, the storm damaged more than 200 homes and displaced over 1,000 people.[49] While in its developmental stages, the precursor low dropped 3 to 5 in (76 to 127 mm) of rainfall across northern Cuba.[13] Candelaria in western Cuba recorded 12.24 in (310.8 mm).[50] At Cienfuegos, 4.25 in (108 mm) of precipitation fell in only three hours.[2] The rains alleviated drought conditions and helped replenish reservoirs, while also causing landslides.[50] The Zaza Reservoir – the largest in Cuba – increased its total water volume by 495,000,000 cubic feet (14,000,000 m3), bringing the levels to 30% capacity. In Batabanó on Cuba's southern coast, 8.5 in (215 mm) of rainfall caused moderate flooding.[51] Near Havana, the electric company shut off power to prevent accidents, while damage occurred to gas lines.[50] United StatesTotal economic losses across the United States reached US$550 million.[2][52] Insured losses to property in Florida reached US$80 million with 14,890 claims.[53] Florida Ahead of the hurricane's landfall, a station south of Apalachicola reported wind gusts of 79 mph (127 km/h) at an elevation of 115 ft (35 m).[54] At sea level, sustained winds reached 52 mph (84 km/h) at Keaton Beach, with gusts 67 mph (108 km/h).[55] While moving ashore, Hermine produced a 5.8 ft (1.8 m) storm surge at Cedar Key.[56] Heavy rainfall occurred across western Florida, reaching 22.36 in (568 mm) over 72 hours at the Lake Tarpon Canal in Pinellas County.[57] The outer rainbands of Hermine spawned an EF0 tornado just southwest of Windermere with a width of 450 ft (140 m) and 80 to 85 mph (129 to 137 km/h) winds. On the ground for 1.2 mi (1.9 km), the twister damaged about 100 trees, along with several fences and windows.[58] The storm spawned three other EF0 tornadoes, all in Taylor County, none of which caused damage.[59] High winds from the hurricane knocked down many trees in northwestern Florida, some of which fell onto power lines and roofs. The resulting power outages affected about 325,000 people,[28] roughly 1% of all homes and businesses in the state.[43] In Leon County, where the state capital Tallahassee is, 57% of homes lost power,[43] including approximately 80% of the city proper, as well as Florida State University.[28] Of the 145,000 homes and businesses that lost electricity, 3,685 were still without power six days after the storm.[59] Strong winds in the Tallahassee area caused trees to fall onto several houses, injuring a number of people.[28] Hermine was the first hurricane to directly affect the city since Hurricane Kate in 1985.[43] Throughout Leon County, 45 homes or businesses were destroyed, 187 suffered severe damage, and 259 experienced minor damage.[59] Losses across Leon County reached $10.3 million.[60]  Storm surge and abnormally high tides caused significant damage along the Gulf Coast of Florida. In Franklin County, coastal flooding occurred in Alligator Point, Apalachicola, and Carrabelle. A total of 27 homes or businesses were demolished, 43 suffered major damage, and 102 others sustained minor damage.[59] Winds in Wakulla County downed a number of trees, with 133 falling on roadways and 7 falling on homes.[59][28] A total of 115 power lines were downed, with about 14,759 customers losing electricity.[59] The Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory in Panacea suffered extensive damage, especially to their educational Living Dock.[61] The Wakulla River at Wakulla Springs reached its second highest level recorded, behind only Hurricane Dennis in 2005. One business was destroyed and four homes sustained severe damage, while an additional forty-three dwellings experienced minor damage.[59] In Jefferson County, much of the impact consisted of downed trees and power lines.[62] About 62% of residents were left without electricity.[63] Strong winds in Madison County left similar impact, but little structural damage. However, the Madison Creative Arts School suffered severe roof damage, while a mansion was damaged by a large falling tree.[64] Twelve people were rescued in Taylor County due to storm surge,[65] including six in Steinhatchee. Throughout the county, approximately 75 homes or businesses were inflicted major damage, while 60 suffered minor impact.[59] At Dekle Beach, the storm damaged several buildings and wrecked a 300 ft (91 m) fishing pier.[28] In Dixie County, storm surge heights generally ranged from 8 to 9 ft (2.4 to 2.7 m) and peaked just inches below observations during the 1993 Storm of the Century. A total of 61 homes or businesses that were demolished, 540 sustained major damage, and 322 suffered minor impact.[59] Much of the damage in Levy County was also due to storm surge, with 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) above average tides observed.[59] In Cedar Key, storm surge washed across the entire island. The only grocery store suffered wind and coastal flood damage, with food scattered on the floor. At a motel, water swept away air conditioners and left seaweed and mud inside. The storm caused an electrical fire that burnt down the clam processing plant. On Dock Street, which contains several restaurants on stilts, the decks and interiors of the restaurants were damaged.[66] The post office and city hall were severely damaged.[67] Storm damage in Cedar Key was estimated at over $10 million.[66] Additionally, over 40 homes and businesses in west Yankeetown were damaged by coastal flooding. Throughout Levy County, one structure was destroyed, 68 suffered major damage, and 51 others received minor impact.[59] Coastal areas of Citrus County suffered from significant flooding; 2,694 structures sustained damage, of which 531 suffered major damage. Total losses in the county reached $102 million.[68]  In Hernando County, the storm destroyed two houses and severely damaged 18 more, with 179 sustaining minor damage; the county damage toll was estimated at $7.8 million.[69] Heavy rainfall in the Tampa Bay Area flooded streets, causing cars to stall, and forced people to evacuate their homes.[56] Power outages affected the local wastewater treatment plant, causing 938,000 US gallons (3,550,000 L) of partially treated sewage to flow into Hillsborough Bay.[70] In Pasco County, 18 people required rescue from high-water vehicles and were transported to nearby shelters.[28] Property damage totaled $111 million,[71] making Hermine one of the costliest storms on record in the county. Of the 2,672 households affected, 7 were destroyed, 305 sustained major damage, and 1,564 sustained minor damage.[72][73] Damage incurred by roads was estimated at $30–50 million.[74] Much of the impact in Hillsborough County was caused by wind, with a gust up to 58 mph (93 km/h) observed at Port Tampa. Throughout the county, 8 homes sustained minor damage, 7 dwellings experienced major damage, and 9 homes were destroyed. Damage was estimated at $800,000.[75] In Hillsborough and Pinellas counties, about 39,000 people lost electricity.[59] Numerous trees were uprooted or snapped in Alachua County, with several damaging homes in Gainesville. A number of power lines were also downed. In Marion County, trees were reported downed in several areas. A falling tree damaged a house, while another fell on a road and was later hit by a car, causing two people to be hospitalized.[76] Additionally, a homeless man camping near Ocala was killed when a tree fell on his tent.[75] In Lake County, wind gusts estimated at 58 mph (93 km/h) downed trees and power lines in several cities, including Clermont, Eustis, Groveland, Mascotte, Mount Dora, and Tavares.[59] In Manatee County, precipitation totals generally ranged from 5 to 10 in (130 to 250 mm), inundating streets in the eastern parts of the county. Residents in Bradenton, located in the western side of the county, evacuated their homes due to freshwater flooding.[59] Coastal flooding also occurred due to tides of 2–3 ft (0.61–0.91 m) above average. Winds reached tropical storm force at the Sarasota–Bradenton International Airport, with damage to roofs and porches, especially in Brandenton and Ellenton. Throughout the county, impacts from the storm left 72 homes with minor damage and 21 others with major impact. Damage in Manatee County reached $5.1 million. Heavy rain fell across Sarasota County, ranging from 4 to 7 in (100 to 180 mm) during the three day period. Widespread street flooding occurred in the eastern portions of the county, while some residents in Sarasota evacuated their homes. Damage caused by flooding reached about $250,000. Along the coast, tides 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m) above normal left major or moderate damage to 34 homes and minor impact to another. Additionally, beach erosion damage occurred at Lido Beach and Turtle Beach. Coastal flooding damage in Sarasota County reached about $4.75 million. In Collier County, coastal flooding left docks and low-lying streets under water, including State Road 92 near Goodland Bay. Everglades Airpark in Everglades City was closed after high water reached the runway.[59] Elsewhere  Hermine weakened while crossing from Florida into Georgia, but still produced sustained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) at Savannah, with gusts to 58 mph (93 km/h).[77] Farther northeast, Folly Island, South Carolina, reported sustained winds of 44 mph (71 km/h) with gusts to 59 mph (95 km/h),[78] and the pier in Duck, North Carolina, reported sustained winds of 58 mph (93 km/h) with gusts to 73 mph (117 km/h).[79] Heavy rainfall occurred through the Carolinas, reaching 10.72 in (272 mm) in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina.[80] At Norfolk International Airport, wind gusts reached 43 mph (69 km/h).[81] In Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, Hermine's passage left around 274,000 people without power.[41][43][82][83] In Georgia, Hermine's winds knocked down trees onto cars and homes, resulting in several injuries in the subsequent cleanup process, although there was no major damage.[43] The storm spawned two EF1 tornadoes in the state. The first, with a 4.83 mi (7.77 km) path, knocked down or broke thousands of trees in Liberty County, some of which fell onto homes. The other struck Skidaway Island and downed hundreds of trees, causing damage to 20 roofs.[84] On St. Simons Island, the storm sank up to five boats at the Morning Star Marina.[76] In southwestern Georgia, impact in several counties was limited to down trees and power lines, including in Berrien, Colquitt, Cook, Dougherty, Grady, Tift, Thomas, Lanier, Mitchell, and Worth counties.[59] A pecan farm near Ray City, located in Berrien County, suffered roughly US$4 million in damage as winds of 40 to 55 mph (64 to 89 km/h) felled about 1,000 trees and ruined 1 million pounds of fruit.[85] In Grady County, about 2,800 customers lost electricity. The storm left power outages in Colquitt County, where a tree fell on a house. Winds in Dougherty County downed tree limbs that damage two roofs, while 200 electrical service losses occurred. In Tift County, trees and power lines were downed on many roadways, including Route 41 and Route 125.[59] It was estimated that Lowndes County experienced sustained winds near 65 mph (105 km/h).[86] The storm downed a number of trees and power lines, with hundreds falling in Valdosta, resulting in the closure of about 90 roads throughout Lowndes County.[59] Some of the trees also fell on houses.[86] Another road was closed after a box culvert washed out.[87] A bridge along Old Quitman Road was damaged and required repairs.[88] Additionally, about 31,000 customers were left without electricity. The winds downed approximately 1,000 pecans trees, leaving about $3 million in damage to the pecan crop. Property damage totaled around $1 million. Sewer systems were overwhelmed by heavy rainfall, causing up a sewage spillage of up to 117,000 gallons.[59]  The storm flooded roads and downed trees in South Carolina, mostly in Beaufort, Bluffton, and Hilton Head Island.[43] At Hilton Head Island, falling trees severely damaged 13 homes, one of which just over two weeks after a tree had fallen in the same manner upon the same house. Damage to the dwellings reached about $250,000. Falling trees damaged at least two homes in Edisto Beach, while strong winds deroofed and ripped sidings off several other residences. In Cottageville, a man was killed after being hit by a car while he was removing a fallen tree from the highway.[89] In the Charleston area, the airport observed a daily rainfall record of 2.32 in (59 mm) on September 2. A number of roads were flooded in downtown Charleston and North Charleston. In Dorchester County, high winds downed a number of trees, some of which caused roads to be closed. A tree also struck a liquid oxygen tank at the medical center in Summerville, causing a leak that forced the closure of all entrances to the complex. Nearly 7,000 people in the county were left without electricity at the height of the storm.[90] Strong winds in eastern North Carolina resulted in sporadic power outages. Hermine spawned two EF1 tornadoes and one EF0 tornado over Outer Banks.[59] One knocking over two trailers and injuring four people.[91] The tornadoes collectively left about $30,000 in damage.[59] High winds knocked over an 18-wheeler tractor-trailer crossing the Alligator River bridge on U.S. Route 64, killing the driver.[41][42] Flooding covered portions of Highway 12, the main roadway through the Outer Banks.[43] Bands of heavy rain associated with Hermine produced rainfall totals of 4 to 8 in (100 to 200 mm) over most of the region, with the highest amounts near the coast. Widespread poor drainage flooding occurred, with a few reports of flash flooding. Damage across Dare County reached $5.5 million;[59] most of the damage was concentrated on Hatteras Island with flooding in Frisco and Hatteras.[92] In Virginia, abnormally high tides resulted in coastal flooding, particularly in the Norfolk area. A number of low-lying and flood prone neighborhoods were inundated, while Willoughby Spit became impassable. Cars parked at Hague Tower apartments were submerged up to their windows. In Virginia Beach, winds downed signs and branches and ripped siding from a hotel. At another hotel, some rooms suffered roof leaks.[93] On eastern Long Island, two fishermen drowned after being swept into the ocean near the Wading River due to rough surf.[94] Their bodies were later recovered in Shoreham.[95] Nantucket offshore Massachusetts recorded sustained winds of 39 mph (63 km/h) on September 5, with gusts to 52 mph (84 km/h).[96] Royal Caribbean's Anthem of the Seas encountered 40 ft (12 m) seas and 112 mph (180 km/h) winds on its trek from New Jersey to Bermuda, leaving several passengers seasick.[97] In Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, minor wind damage occurred because trees were still fully leaved in those states. Coastal flooding was limited due to storm surge peaking at low tide.[59] AftermathAfter Hermine exited the state, Florida governor Rick Scott took an aerial tour of the damage in Cedar Key and Steinhatchee, pledging that affected businesses would receive assistance from the state government.[43] On September 20, Governor Scott submitted a request to the federal government for individual disaster assistance in 12 counties and public assistance in 15 counties. United States president Barack Obama issued a disaster declaration on September 28. Residents and households in Citrus, Dixie, Hernando, Hillsborough, Leon, Levy, Pasco, and Pinellas counties became eligible for aid. In Citrus, Dixie, Franklin, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Pasco, Pinellas, Suwannee, Taylor, and Wakulla counties, money was allotted to state and local governments as well as some private, nonprofit organizations on a cost-sharing basis; this fund allowed for emergency work on or replacement of buildings damaged by the storm. Additionally, the state of Florida received money from the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program for hazard mitigation.[98] However, the disaster declaration was eventually expanded to several other counties. By November 2, Alachua, Baker, Columbia, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Manatee, Marion, Sarasota, Sumter, and Union counties were eligible for public assistance or both public and individual assistance.[99] In addition to federal aid, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) opened five disaster recovery centers, with one in Citrus County, one in Dixie County, one in Leon County, and two in Levy County. These disaster centers were staffed by representatives of FEMA, the Florida Division of Emergency Management, the Small Business Administration, and other state agencies. FEMA agents also went door-to-door in Tallahassee to ask residents about damage to their property.[100] In Lee County, crews were deployed to collect plant debris.[101] Due to storm damage, officials in Hernando County provided curbside debris removal, and two parks were closed.[102] The post office in Cedar Key was damaged severely enough to remain closed for repairs until February,[103] while the city hall has yet[as of?] to reopen. In the meantime, city business has been conducted in a double-wide trailer near the city hall.[104] In Franklin County, the St. George Island Bridge was reopened just 15 hours after its closure to allow access to cleanup crews.[105] See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Hermine (2016). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||