|

Huo Qubing

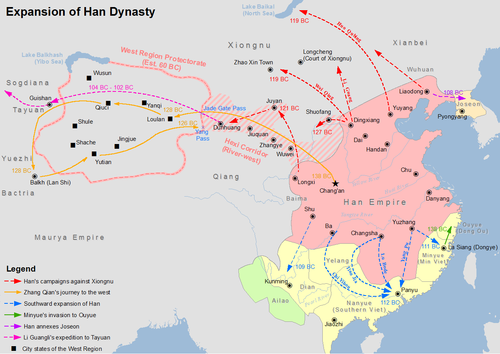

Huo Qubing (140 BC – c.October 117 BC,[1] formerly Ho Ch'ii-ping) was a Chinese military general and politician of the Western Han dynasty during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han. He was a nephew of the general Wei Qing and Empress Wei Zifu (Emperor Wu's wife), and a half-brother of the statesman Huo Guang.[2] Along with Wei Qing, he led a campaign into the Gobi Desert of what is now Mongolia to defeat the Xiongnu nomadic confederation, winning decisive victories such as the Battle of Mobei in 119 BC. Huo Qubing was one of the most legendary commanders in Chinese history, and still lives on in Chinese culture today. Early lifeHuo Qubing was an illegitimate son from the love affair between Wei Shaoer (衛少兒), the daughter of a lowly maid from the household of Princess Pingyang (Emperor Wu's older sister), and Huo Zhongru (霍仲孺), a low-ranking civil servant employed there at the time.[3] However, Huo Zhongru did not want to marry a lower class serf girl like Wei Shaoer, so he abandoned her and went away to marry a woman from his home town instead. Wei Shaoer insisted on keeping the child, raising him with help of her siblings. When Huo Qubing was around two years old, his younger aunt Wei Zifu, who was serving as an in-house singer/dancer for Princess Pingyang, caught the attention of the young Emperor Wu, who took her and her half-brother Wei Qing back to his palace in the capital, Chang'an. More than a year later, the newly favoured concubine Wei Zifu became pregnant with Emperor Wu's first child, earning her the jealousy and hatred of Emperor Wu's then empress consort, Empress Chen. Empress Chen's mother, Grand Princess[4] Guantao (館陶長公主), then attempted to retaliate against Wei Zifu by kidnapping and attempting to murder Wei Qing, who was then serving as a horseman at the Jianzhang Camp (建章營, Emperor Wu's royal guards). After Wei Qing was rescued by fellow palace guards led by his close friend Gongsun Ao (公孫敖), Emperor Wu took the opportunity to humiliate Empress Chen and Princess Guantao by promoting Wei Zifu to a consort (夫人, a concubine position lower only to the Empress) and Wei Qing to the triple role of Chief of Jianzhang Camp (建章監), Chief of Staff (侍中), and Chief Councillor (太中大夫), effectively making him one of Emperor Wu's closest lieutenants. The rest of the Wei family were also well rewarded, including the decreed marriage of Wei Shaoer's older sister Wei Junru (衛君孺) to Emperor Wu's adviser, Gongsun He (公孫賀). At the time, Wei Shaoer was romantically engaged with Chen Zhang (陳掌), a great-grandson of Emperor Gaozu's adviser Chen Ping. Their relationship was also legitimized by Emperor Wu through the form of decreed marriage.[5] Through the rise of the Wei family, the young Huo Qubing grew up in prosperity and prestige. Military careerHuo Qubing exhibited outstanding military talent even as a teenager. Emperor Wu saw Huo's potential and made Huo his personal assistant.  In 123 BC, Emperor Wu sent Wei Qing from Dingxiang (定襄) to engage the invading Xiongnu, and appointed the 18-year-old Huo Qubing to serve as the Captain of Piaoyao (票姚校尉) under his uncle,[6] seeing real combat for the first time. Although Wei Qing was able to kill or capture more than 10,000 Xiongnu soldiers, part of his vanguard forces, a 3,000-strong regiment commanded by generals Su Jian (蘇建, father of the Han diplomat and statesman, Su Wu) and Zhao Xin (趙信, a surrendered Xiongnu prince) was outnumbered and annihilated after encountering the Xiongnu force led by Yizhixie Chanyu (伊稚斜單于). Zhao Xin defected on the field with his 800 ethnic Xiongnu subordinates, while Su Jian escaped after losing all his men in the desperate fighting. Due to the loss of this detachment, Wei Qing's troops did not earn any promotion, but Huo Qubing distinguished himself by leading a long-distance search-and-destroy mission with 800 light cavalrymen,[7] killing the Chanyu's grandfather and over 2,000 enemy troops, as well as capturing numerous Xiongnu nobles. A very impressed Emperor Wu then made Huo Qubing the Marquess of Guanjun (Champion) (冠軍侯) with a march of 2,500 households.[8] In 121 BC, Emperor Wu deployed Huo Qubing twice in that year against the Xiongnu in the Hexi Corridor. During spring, Huo Qubing led 10,000 cavalry, fought through five Western Regions kingdoms within 6 days, advanced over 1,000 li over Mount Yanzhi (焉支山), killed two Xiongnu princes along with nearly 9,000 enemy troops, and captured several Xiongnu nobles as well as the Golden Man idol used by Xiongnu as an artifact for holy rituals.[9] For this achievement, his march was increased by 2,200 households.[10] During the summer of the same year, Xiongnu attacked the Dai Commandery and Yanmen. Huo Qubing set off from Longxi (modern-day Gansu) with over 10,000 cavalry, supported by Gongsun Ao, who set off from the Beidi Commandery (北地郡). Despite Gongsun Ao failing to keep up, Huo Qubing travelled over 2,000 li without backup, all the way past Juyan Lake to Qilian Mountains, killing over 30,000 Xiongnu soldiers and capturing a dozen Xiongnu princes. His march was then increased further by an additional 5,400 households for the victory.  Huo Qubing's victories dealt heavy blows to the tribes of the Xiongnu princes of Hunxie (渾邪王) and Xiutu (休屠王) that occupied the Hexi Corridor. Out of frustration, Yizhixie Chanyu wanted to mercilessly execute those two princes as punishment. The Prince of Hunxie contacted the Han government in autumn of 121 BC to negotiate a surrender. Failing to persuade his fellow prince to do the same, he killed the Prince of Xiutu and ordered Xiutu's forces to also surrender. When the two tribes went to meet the Han forces, Xiutu's forces rioted. Seeing the situation changed, Huo Qubing alone headed to the Xiongnu camp. There, the general ordered the Prince of Hunxie to calm his men and stand down before putting down 8,000 Xiongnu men who refused to disarm, effectively quelling the riot. The Hunxie tribe was then resettled into the Central Plain. The surrender of the Xiutu and Hunxie tribes stripped Xiongnu of any control over the Western Regions, depriving them of a large grazing area. As a result, the Han dynasty successfully opened up the Northern Silk Road, allowing direct trade access to Central Asia. This also provided a new supply of high-quality horse breeds from Central Asia, including the famed Ferghana horse (ancestors of the modern Akhal-Teke), further strengthening the Han army. Emperor Wu then reinforced this strategic asset by establishing five commanderies and constructing a length of fortified wall along the border of the Hexi Corridor. He colonised the area with 700,000 Chinese soldier-settlers. After the series of defeats by Wei Qing and Huo Qubing, Yizhixie Chanyu took Zhao Xin's advice and retreated with his tribes to the north of the Gobi Desert, hoping that the barren land would serve as a natural barrier against Han offensives. Emperor Wu however, was far from giving up, and planned a massive expeditionary campaign in 119 BC. Han forces were deployed in two separate columns, each consisting of 50,000 cavalry and over 100,000 infantry, with Wei Qing and Huo Qubing serving as the supreme commander for each. Emperor Wu, who had been distancing Wei Qing and giving the younger Huo Qubing more attention and favour, hoped that Huo would engage the stronger Chanyu's tribe and preferentially assigned him the most elite troopers. The initial plan called for Huo Qubing to attack from Dingxiang (定襄, modern-day Qingshuihe County, Inner Mongolia) and engage the Chanyu, with Wei Qing supporting him in the east from Dai Commandery (代郡, modern-day, Yu County, Hebei) to engage the Left Worthy Prince (左賢王). However, a Xiongnu prisoner of war confessed that the Chanyu's main force was at the east side. Unaware that this was actually false information provided by the Xiongnu, Emperor Wu ordered the two columns to switch routes, with Wei Qing now setting off on the western side from Dingxiang, and Huo Qubing marching on the eastern side from the Dai Commandery. Battles at the eastern Dai Commandery theatre were quite straightforward, as Huo Qubing's forces were far superior to their enemies. Huo Qubing advanced over 2,000 li and directly engaged the Left Worthy Prince in a swift and decisive battle. He quickly encircled and overran the Xiongnu, killing over 70,000 men, and capturing three lords and 83 nobles, while suffering a 20% casualty rate that was quickly resupplied from local captives. He then went on to conduct a series of rituals upon his arrival at the Khentii Mountains (狼居胥山, and the more northern 姑衍山) to symbolize the historic Han victory, then continued his pursuit as far as Lake Baikal (瀚海), effectively annihilating the Xiongnu clan and allowing conquering tribe such as the Donghu People to retake back their land to establish their own confederacy to declared independent from Xiongnu Overlord following the subjugation for over a few decade.[13] A separate division led by Lu Bode (路博德), set off on a strategically flanking route from Right Beiping (右北平, modern-day Ningcheng County, Inner Mongolia), joined forces with Huo Qubing after arriving in time with 2,800 enemy kills, and the combined forces then returned in triumph. This victory earned Huo Qubing 5,800 households of fiefdom as a reward,[14] making him more distinguished than his uncle Wei Qing.[15] At the height of his career, many low-ranking commanders previously served under Wei Qing voluntarily transferred to Huo Qubing's service in the hope of achieving military glory with him.[16] Death and legacy  Emperor Wu offered to help Huo Qubing build up a household for marriage. Huo Qubing, however, answered that "the Xiongnu are not yet eliminated, why should I start a family?" (匈奴未滅,何以家為?),[17] a statement that became an inspirational Chinese patriotic motto. Though Huo Qubing was recorded as a quietly spoken man of few words, he was far from humble.[18] Sima Qian noted in Shiji that Huo Qubing paid little regard to his men,[19] refusing to share his food with his soldiers,[20] and regularly ordering his troops to conduct cuju games despite them being short on rations.[21] When Emperor Wu suggested him to study The Art of War by Sun Tzu and Wuzi by Wu Qi, Huo Qubing claimed that he naturally understood war strategies and had no need to study.[22] When his subordinate Li Gan (李敢, son of Li Guang) assaulted Wei Qing, the latter forgave the incident. Huo Qubing, on the other hand, refused to tolerate such disrespect towards his uncle and personally shot Li Gan during a hunting trip. Emperor Wu covered for Qubing, stating that Li Gan was "killed by a deer".[23] When it came to military glory, Huo Qubing was said to be more generous. One story about him told of when Emperor Wu awarded Huo a jar of precious wine for his achievement, he poured it into a creek so all his men drinking the water could share a taste of it, giving the name to the city of Jiuquan (酒泉, literally "wine spring"). Huo Qubing died in 117 BC at the early age of 23. After Huo Qubing's death, the aggrieved Emperor Wu ordered the elite troops from the five border commanderies to line up all the way from Chang'an to Maoling, where Huo Qubing's tomb was constructed in the shape of the Qilian Mountains to commemorate his military achievements.[24] Huo Qubing was then posthumously appointed the title Marquess of Jinghuan (景桓侯),[25] and a large "Horse Stomping Xiongnu" (馬踏匈奴) stone statue was built in front of his tomb,[26] near Emperor Wu's tomb of Maoling. Huo Qubing was among the most decorated military commanders in Chinese history. The Eastern Han dynasty historian Ban Gu summarized in his Book of Han Huo Qubing's achievements with a poem:

Huo Qubing's half-brother, Huo Guang, whom he took custody away from his father, was later a great statesman who was the chief counsel for Emperor Zhao, and was instrumental in the succession of Emperor Xuan to the throne after Emperor Zhao's death. Huo Qubing's son, Huo Shàn (霍嬗), succeeded him as the Marquess of Jinghuan but died young in 110 BC. So Huo Qubing's title became extinct. His grandson Huo Shān (霍山, later Marquess of Leping) and Huo Yun (霍云, later Marquess of Guanyang) were involved in a failed plot to overthrow Emperor Xuan of Han in 66 BC, resulting in both of them committing suicide and the Huo clan being executed. It is presumed that no male descendants of Huo Qubing or Huo Guang survived, as during the reign of Emperor Ping of Han, it was Huo Yang, a great-grandson of Huo Qubing's paternal cousin, who was chosen as the descendant of Huo Guang to be the Marquess of Bolu. Huo Qubing and monumental statuary The Book of Han records that in 121 BCE when General Huo Qubing defeated the armies of King Xiutu (休屠), in modern-day Gansu, he "captured a golden (or gilded) man used by the King of Xiutu to worship Heaven".[28][29] This golden statue was unlikely Buddhist, as the Xiongnu were unrelated to this religion.[30] The statues were later moved to the Yunyang 雲陽 Temple, near or in the royal summer Ganquan Palace 甘泉 (modern Xianyang, Shaanxi), which had also the capital of the Qin Empire.[28][31] In Cave 323 in Mogao caves (near Dunhuang in the Tarim Basin), Emperor Wudi is shown worshipping two golden statues, with the following inscription (which closely paraphrases the traditional accounts of Huo Qubing's expedition):[28]

The Han expedition to the west and the capture of booty by general Huo Qubing is well documented, but the later Buddhist interpretation at the Mogao Caves of the worship of these statues as a means to propagate Buddhism in China is probably apocryphal, since Han Wudi is not known to have ever worshipped the Buddha, and Buddhist statues probably did not exist yet at this time.[27] First monumental stone statues in China There are no known examples of monumental stone statuary in China before the stone sculptures at Huo Qubing's Mausoleum.[33] In particular, his mausoleum was adorned with a monumental stone statue depicting a horse trampling a Xiongnu warrior.[32] In literary sources, there is only a single 3rd-4th century CE record of a possible earlier example: two alleged monumental stone statues of qilin (Chinese unicorns) that had been set up on top of the tomb of the First Emperor Qin Shihuang.[34] Huo Qubing must have been influenced by stone statues he saw during his campaigns in the west.[35] The cultural tradition of monumental stone sculpture too seems to have followed a process of West-East diffusion, starting from Egypt and Babylonia to reach Greece, until finally reaching India with the Pillars of Ashoka (268-232 BCE) and China around the 2nd century BCE. The stone carvings of the tombs of Huo Qubing and Zhang Qian may have been influenced by their contact and experiences with Western Asian cultures (Central Asian culture and other culture diffused by the silk road). [36][37] The Mausoleum of Huo Qubing (located in Maoling at 34°20′28″N 108°34′53″E / 34.341214°N 108.581381°E, near the Mausoleum of Han Wudi) has 15 more stone sculptures. These are less naturalistic than the "Horse trampling a Xiongnu", and tend to follow the natural shape of the stone, with details of the figures only emerging in high-relief.[38]

Popular cultureHuo Qubing is one of the 32 historical figures who appear as special characters in the video game Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI by Koei. Huo Qubing was played by Li Junfeng (李俊锋) in the popular 2005 historical epics TV series The Emperor in Han Dynasty (汉武大帝). Huo Qubing was played by Eddie Peng (彭于晏) under the name of Wei Wuji (卫无忌) in the popular romance Chinese drama Sound of the Desert (风中奇缘) derived from the book Da Mo Yao/Ballad of the Desert (大漠谣) by famous novel writer Tong Hua. Huo Qubing is also mentioned in the blockbuster film Dragon Blade, where the main character, played by Jackie Chan, is said to have been raised up by him. Actor Feng Shaofeng portrays the general in brief flashbacks. See alsoNotes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||