|

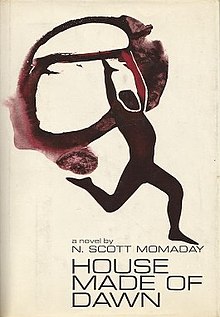

House Made of Dawn

House Made of Dawn is a 1968 novel by N. Scott Momaday, widely credited as leading the way for the breakthrough of Native American literature into the mainstream. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1969, and has also been noted for its significance in Native American anthropology.[2] BackgroundWith 198 pages, House Made of Dawn was conceived first as a series of poems, and then replanned as stories, and finally shaped into a novel. It is based largely on Momaday's firsthand knowledge of life at Jemez Pueblo. Like the novel's protagonist, Abel, Momaday lived both inside and outside of mainstream society, growing up on reservations and later attending school and teaching at major universities. In the novel Momaday combines his personal experiences with his imagination—something his father, Al Momaday, and his mother taught him to do, according to his memoir The Names. Details in the novel correspond to real-life occurrences. According to one of Momaday's letters:

According to one historian, the novel is highly accurate in its portrayal of a peyote service, though in southern California such services normally take place in the desert, not the city.[3] In 1972, an independent feature film based on House Made of Dawn by Richardson Morse was released.[4] Momaday and Morse wrote the script. Larry Littlebird starred. Considered a "classic", the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) went to great efforts to preserve the film, now housing all film elements in its film and media archives, which provide study copies.[4] Plot summaryPart I: The LonghairHouse Made of Dawn begins with the protagonist, Abel, returning to his reservation in New Mexico after fighting in World War II. The war has left him emotionally devastated and he arrives too drunk to recognize his grandfather, Francisco. Now an old man with a lame leg, Francisco had earlier been a respected hunter and participant in the village's religious ceremonies. He raised Abel after the death of Abel's mother and older brother, Vidal. Francisco instilled in Abel a sense of native traditions and values, but the war and other events severed Abel's connections to that world of spiritual and physical wholeness and connectedness to the land and its people, a world known as a "house made of dawn". After arriving in the village, Abel attains a job through Father Olguin chopping wood for Angela St. John, a rich white woman who is visiting the area to bathe in the mineral waters. Angela seduces Abel to distract herself from her own unhappiness, but also because she senses an animal-like quality in Abel. She promises to help him leave the reservation to find better means of employment. Possibly as a result of this affair, Abel realizes that his return to the reservation has been unsuccessful. He no longer feels at home and he is confused. His turmoil becomes clearer when he is beaten in a game of horsemanship by a local albino Indian named Juan Reyes, described as "the white man". Deciding Juan is a witch, Abel stabs him to death outside of a bar. Abel is then found guilty of murder and sent to jail. Part II: The Priest of the SunPart II takes place in Los Angeles, California six and a half years later. Abel has been released from prison and unites with a local group of Indians. The leader of the group, Reverend John Big Bluff Tosamah, Priest of the Sun, teases Abel as a "longhair" who is unable to assimilate to the demands of the modern world. However, Abel befriends a man named Ben Benally from a reservation in New Mexico and develops an intimate relationship with Milly, a kind, blonde social worker. However, his overall situation has not improved and Abel ends up drunk on the beach with his hands, head, and upper body beaten and broken. Memories run through his mind of the reservation, the war, jail, and Milly. Abel eventually finds the strength to pick himself up and he stumbles across town to the apartment he shares with Ben. Part III: The Night ChanterBen puts Abel on a train back to the reservation and narrates what has happened to Abel in Los Angeles. Life had not been easy for Abel in the city. First, he was ridiculed by Reverend Tosamah during a poker game with the Indian group. Abel is too drunk to fight back. He remains drunk for the next two days and misses work. When he returns to his job, the boss harasses him and Abel quits. A downward spiral begins and Abel continues to get drunk every day, borrow money from Ben and Milly, and laze around the apartment. Fed up with Abel's behavior, Ben throws him out of the apartment. Abel then seeks revenge on Martinez, a corrupt policeman who robbed Ben one night and hit Abel across the knuckles with his big stick. Abel finds Martinez and is almost beaten to death. While Abel is in the hospital recovering, Ben calls Angela who visits him and revives his spirit, just as he helped revive her spirit years ago, by reciting a story about a bear and a maiden which incidentally matches an old Navajo myth. Part IV: The Dawn RunnerAbel returns to the reservation in New Mexico to take care of his grandfather, who is dying. His grandfather tells him the stories from his youth and stresses the importance of staying connected to his people's traditions. When the time comes, Abel dresses his grandfather for burial and smears his own body with ashes. As the dawn breaks, Abel begins to run. He is participating in a ritual his grandfather told him about—the race of the dead. As he runs, Abel begins to sing for himself and Francisco. He is coming back to his people and his place in the world. Literary significance and criticismHouse Made of Dawn produced no extensive commentary when it was first published—perhaps, as William James Smith mused in a review of the work in Commonwealth LXXXVIII (20 September 1968), because "it seems slightly un-American to criticize an American Indian's novel"—and its subject matter and theme did not seem to conform to the prescription above. Early reviewers such as Marshall Sprague in his "Anglos and Indians", New York Times Book Review (9 June 1968) complained that the novel contained "plenty of haze" but suggested that perhaps this was inevitable in rendering "the mysteries of cultures different from our own" and then goes on to describe this as "one reason why [the story] rings so true". Sprague also discussed the seeming contradiction of writing about a native oral culture—especially in English, the language of the so-called oppressor. He continues, "The mysteries of cultures different from our own cannot be explained in a short novel, even by an artist as talented as Mr. Momaday".[5] The many critics—such as Carole Oleson in her "The Remembered Earth: Momaday's House Made of Dawn", South Dakota Review II (Spring 1973)—who have given the novel extended analysis acknowledge that much more explanation is needed "before outsiders can fully appreciate all the subtleties of House Made of Dawn". Baine Kerr has elaborated this point to suggest that Momaday has used "the modern Anglo novel [as] a vehicle for a sacred text", that in it he is "attempting to transliterate Indian culture, myth, and sensibility into an alien art form, without loss". However, some commentators have been more critical. In reviewing the "disappointing" novel for Commonweal (September 20, 1968), William James Smith chastised Momaday for his mannered style: "[He] writes in a lyric vein that borrows heavily from some of the slacker rhythms of the King James Bible ... It makes you itch for a blue pencil to knock out all the intensified words that maintain the soporific flow." Other critics said it was nothing but "an interesting variation of the old alienation theme"; "a social statement rather than ... a substantial artistic achievement"; "a memorable failure"; "a reflection, not a novel in the comprehensive sense of the word" with "awkward dialogue and affected description"; "a batch of dazzling fragments". Overall, the book has come to be seen as a success. Sprague concluded in his article that the novel was superb, and Momaday was widely praised for the novel's rich description of Indian life. Now there is a greater recognition of Momaday's fictional art, and critics have come to recognise its unique achievement as a novel. Despite a qualified reception the novel had succeeded in making its impact even on earlier critics though they were not sure of their own responses. They found it "a story of considerable power and beauty", "strong in imaginative imagery", creating a "world of wonder and exhilarating vastness". In more recent criticism there are signs of greater clarity of understanding of Momaday's achievement. In his review (which appeared in Western American Literature 5, Spring 1970), John Z. Bennett had pointed out how through "a remarkable synthesis of poetic mode and profound emotional and intellectual insight into the Indians' perduring human status" Momaday's novel becomes at last the very act it is dramatizing, an artistic act, a "creation hymn". AwardsInfluenceCritic Kenneth Lincoln identified the Pulitzer for House Made of Dawn as the moment that sparked the Native American Renaissance. Many major American Indian novelists (e.g. Paula Gunn Allen, Leslie Marmon Silko, Gerald Vizenor, James Welch, Sherman Alexie and Louise Erdrich) have cited the novel as a significant inspiration for their own work. PublishersOriginally published by Harper & Row, editions have subsequently been brought out by HarperCollins, the Penguin Group, Econo-Clad Books and the University of Arizona Press. See also

Release details

Footnotes

References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||