|

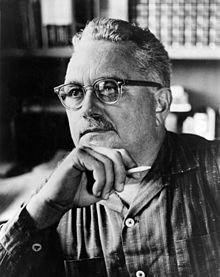

Hodding Carter

William Hodding Carter II (February 3, 1907 – April 4, 1972) was an American progressive journalist and author. Among other distinctions in his career, Carter was a Nieman Fellow and Pulitzer Prize winner. He died in Greenville, Mississippi, of a heart attack at the age of sixty-five. He is interred in the Greenville Cemetery. BiographyEarly life and educationCarter was born in Hammond, Louisiana, the largest community in Tangipahoa Parish, in southeastern Louisiana. His parents were farmer William Hodding Carter I and Irma, née Dutartre.[1] He was valedictorian of the Hammond High School class of 1923. Carter attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine (1927), and the Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University (1928). He returned to Louisiana upon graduating. According to Ann Waldron, the young Carter was an outspoken white supremacist, yet he began to alter his thinking when he returned to the South to live.[2] Career backgroundAfter a year as a teaching fellow at Tulane University in New Orleans (1928–1929), Carter worked as reporter for the New Orleans Item-Tribune (1929), United Press in New Orleans (1930), and the Associated Press in Jackson, Mississippi, (1931–32). With his wife, Betty Werlein of New Orleans, Carter founded the Hammond Daily Courier, in 1932. The paper was known for its opposition to popular Louisiana governor Huey Pierce Long Jr., but its support for the national Democratic Party. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing in 1946 for his editorials on intolerance, as exemplified by "Go for Broke", lambasting the ill treatment of Japanese American (Nisei) soldiers returning from World War II. He was a professor for a single semester at Tulane. Fighting intoleranceHe also wrote editorials in the Greenville Delta Democrat-Times regarding social and economic intolerance in the Deep South that won him widespread acclaim and the moniker "Spokesman of the New South". Carter wrote a caustic article for Look magazine which detailed the menacing spread of a chapter of the White Citizens' Council. The article was attacked on the floor of the Mississippi House of Representatives as a "Willful lie by a nigger-loving editor". Carter responded in a front-page editorial:

Personal lifeHe had a son Hodding Carter III, born in 1935, who became State Department spokesman during the Carter administration and achieved a degree of notoriety by often appearing on television news.[4] Carter was strongly opposed to the Munich Conference, which ceded the Sudetenland to Adolf Hitler. Carter rushed into World War II service. While stationed at Camp Blanding in Florida, he lost the sight in his right eye during a training exercise. He thereafter served in the Intelligence Division and continued his journalistic activities by editing the Middle East division of Yank and Stars and Stripes in Cairo, Egypt, and writing three books.[5] Politics and the KennedysCarter was an unabashed supporter of the Kennedys and their quest for the American Presidency. He had dinner with Bobby Kennedy and his family the night before Kennedy was assassinated in 1968. Carter had also been working for him "campaigning, making talks, and writing ghost speeches".[6] On a flight home, Carter learned of Kennedy's death and was devastated. A passenger on the plane said, "Well, we got that son-of-a-bitch, didn't we?" Carter responded, "Who are you talking about?" The passenger said, "You know damn well who I'm talking about", to which Carter responded by saying "You're just a son-of-a-bitch", and then punching the passenger in the mouth.[7] CriticismColumnist Eric Alterman, in a book review of The Race Beat (2006) for The Nation discusses how Carter and other Southern journalists were "moderate defenders" of the South. That is, they were apologists for the South during the pre-civil rights era. Alterman says, "'Enlightened'" Southern editors, especially...Mississippi's Hodding Carter, Jr., sold [Northerners] a Chalabi-like dream of steady, nonviolent progress that belied the violent savagery that lay in wait for those who stepped out of line".[8] One of the reasons segregation had been a success, according to Alterman, is "the way newspapers had neglected it". In Hodding Carter: The Reconstruction of a Racist, author Ann Waldron makes the case that although Carter crusaded for racial equality, he hedged on condemning segregation, and that after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, he attacked the intransigent White Citizens' Council, but only supported gradual integration.[9] In defense of Carter, Claude Sitton, writing about Waldron's book in The New York Times says, "[R]eaders of today will ask how an editor who opposed enactment of a federal antilynching law as unnecessary and public school desegregation in Mississippi as unwise can be called a champion of racial justice. The answer, which she gives in the book's introduction, lies in the context of the times...Absent his efforts and those of other Southern editors of courage and like mind, change would have come far more slowly and at far greater cost."[10] ResearchMitchell Library at Mississippi State University in Starkville holds Carter's personal papers. Books

References

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||