|

History of West Palm Beach, Florida

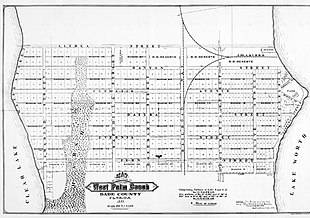

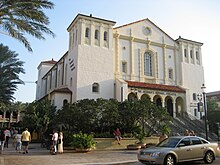

The history of West Palm Beach, Florida, began more than 5,000 years ago with the arrival of the first aboriginal natives. Native American tribes such as the Jaegas inhabited the area. Though control of Florida changed among Spain, England, the United States, and the Confederate States of America, the area remained largely undeveloped until the 20th century. By the 1870s and 1880s, non-Native American settlers had inhabited areas in the vicinity of West Palm Beach and referred to the settlement as "Lake Worth Country". However, the population remained very small until the arrival of Henry Flagler in the 1890s. Flagler constructed hotels and resorts in Palm Beach to create a travel destination for affluent tourists, who could travel there via his railroad beginning in 1894. Flagler originally intended for West Palm Beach to serve as a residential area for the workers at his hotels in Palm Beach. In 1893, George W. Potter surveyed and platted the original 48 blocks of the city. West Palm Beach would be incorporated as a town on November 5, 1894, before becoming a city in 1903. Upon the establishment of Palm Beach County in 1909, West Palm Beach received the designation of county seat. The city developed much more rapidly during the 1920s land boom, which saw a nearly four-fold increase in population between 1920 and 1927 and the construction of many of the city's historical buildings and neighborhoods. However, the 1928 hurricane – which devastated the city – and end of the land boom ushered the area into an era of economic decline just prior to the onset of the Great Depression. West Palm Beach experienced an economic rebound in the post-World War II years, as veterans who trained at Morrison Field vacationed or relocated to the area. The city also markedly expanded westward in the 1950s and 1960s, with thousands of acres of wetlands drained and filled. In the latter decade, a municipal stadium, auditorium, and mall were built on the newly drained and filled land. Commercial development west of the original city boundaries led to urban decay in downtown by the 1980s. However, the beautification of Clematis Street beginning in the early 1990s, and the opening of CityPlace in 2000 led to a revitalized downtown area. In 2018, the United States Census Bureau estimated that the city had a population of 111,398.[1] Prior to incorporation (before November 1894) Archaeological evidence suggests that the Jaegas settled in modern-day Palm Beach County as many as 5,000 years ago.[2] The first contact between Native Americans in the area and Europeans occurred in 1513 upon Juan Ponce de León's landfall at the Jupiter Inlet.[3] Europeans encountered a thriving native population, the Mayaimi in the Lake Okeechobee Basin, while the Jaegas and Ais resided east of Lake Okeechobee and along the east coast north of the Tequestas. When the Spanish arrived, there were perhaps about 20,000 Native Americans in South Florida. The native peoples had all but been wiped out through war, enslavement, or European diseases, by the time the English gained control of Florida in 1763.[2] Other native people from Alabama and Georgia moved into Florida in the early 18th century. They were of varied ancestry, but Europeans called them all Creeks. In Florida, they were known as the Seminole and Miccosukee Indians. American settlers and Seminoles fought against each other due to land and escaped slaves, who were granted protection by the Seminoles. They resisted the government's efforts to move them to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi. The Seminoles and the United States government fought with each other in three wars between 1818 and 1858. By the end of the third war, very few Seminoles remained in Florida.[4] The area that was to become West Palm Beach was settled in the late 1870s and 1880s by a few hundred settlers who called the vicinity "Lake Worth Country".[5] These settlers were a diverse community from different parts of the United States and the world.[5] They included founding families such as the Potters and the Lainharts, who would go on to become leading members of the business community in the fledgling city.[6] Irving R. Henry filed the first homestead claim in 1880, claiming 131 acres (53 ha). Henry would later sell the land to Captain O. S. Porter.[7] The first non-Native American settlers in Palm Beach County resided around Lake Worth, – an enclosed freshwater lake at the time – named after Colonel William Jenkins Worth, who served in the Second Seminole War in 1842.[8] Reverend Elbridge Gale and his son are believed to have constructed the first log cabin on the western shore of Lake Worth, located near where the intersection of 29th Street and Poinsettia Avenue stands today.[9] Most settlers engaged in the growing of tropical fruits and vegetables for shipment to the north via Lake Worth and the Indian River.[10]  In 1890, the United States Census counted over 200 people settled along Lake Worth in the vicinity of what would become West Palm Beach.[11] The area at this time also boasted a hotel, the "Cocoanut House", a church, and a post office.[5] Henry Flagler, who was instrumental to Palm Beach County's development in the late 19th century and early 20th century, first visited in 1892, describing the area as a "veritable paradise".[12] The first newspaper in the area, The Gazetteer, began publication in 1893, but the paper ceased printing issues after burning in a downtown fire in 1896.[13] Additionally, West Palm Beach's first business, Lainhart and Potter Lumber Company, and the first bank, Dade County State Bank, were both established in 1893. That year, Flagler began planning a city to house the employees working in the two grand hotels on the neighboring island of Palm Beach.[11] Flagler paid two area settlers, Porter and Louie Hillhouse, a combined sum of $45,000 for the original town site. Flagler hired George W. Potter, Dade County's first surveyor, to set aside 48 blocks for development stretching from Clear Lake to Lake Worth, an area that would later become West Palm Beach.[6] The east-to-west oriented streets were named alphabetically from north to south – Althea, Banyan, Clematis, Datura, Evernia, Fern – while some of the north-to-south roads were called Lantana, Narcissus, Olive, Poinsettia, Rosemary, and Tamarind. Most of these names are still used today.[14] Over in Palm Beach, construction began on the Royal Poinciana Hotel on May 1, 1893.[12] The lots in West Palm Beach were auctioned off in the ballroom of the Royal Poinciana on February 4, 1894,[15] one week before the hotel opened for business.[16] In late March, Flagler's Florida East Coast Railway reached West Palm Beach.[12] Incorporation and early years (November 1894 to 1909) On November 5, 1894, residents met at the "Calaboose", which served as the first jail and police station. The building formerly stood at Clematis Street and Poinsettia, now Dixie Highway. The 78 people there voted on a motion to incorporate, with 77 in favor and 1 against. They also decided to name the municipality "West Palm Beach", originally a town.[17] This made West Palm Beach the first incorporated municipality in the county and in Southeast Florida.[18] On the following day, 78 people also met to vote on the new town officers. Voters elected John S. Earman as the first mayor, while Henry J. Burkhardt, E. H. Dimick, J. M. Garland, H. T. Grant, J. F. Lamond, and George Zapf became the town's first aldermen. Eli Sims and W. L. Tolbert were chosen to be town clerk and town marshal, respectively.[19] Later in November 1894, the Flagler Alerts, an all-volunteer fire department, was established as the first fire department in the city.[15] Although Flagler intended for the West Palm Beach area to be the southern terminus of his railroad, the track was extended farther southward to Miami after two severe freezes in the winter of 1894–95. The Weather Bureau office, then located in Jupiter, recorded temperatures of 24 and 27 °F (−4 and −3 °C) on December 29, 1894, and February 9, 1895, respectively. Though the railroad continued southward to Miami and eventually to Key West,[20] Flagler and his workers continued building structures in the early years of Palm Beach and West Palm Beach. Completion of a railroad bridge across Lake Worth in 1895 allowed passengers to directly reach Palm Beach from West Palm Beach.[7] A census conducted that year reported a population of 1,192 people. However, the town's population decreased by more than half during the second half of the 1890s due to damage to the citrus industry caused by the aforementioned freezes, a brief cessation in construction activity, and national recessions.[21]: 9  At the V-shaped split at the east end of Clematis Street, "City Park" (later known as Flagler Park) was constructed, which contained a bandstand, a field for impromptu baseball games, and by 1896, a free "reading room". Two large fires devastated downtown West Palm Beach in early 1896.[7] On January 2, an overheated stove at Midway Plaisance Saloon and Restaurant resulted in a fire that spread across all of Banyan Street. The next fire occurred on February 20, ignited after a man accidentally knocked over an oil lamp. Much of Narcissus Street burned, including the building housing The Gazetteer, which never resumed publication.[22] The fire led to stricter building codes, with structures required to be made of bricks.[7] Wilmon Whilldin, who served as mayor from 1898 to 1899, led a transition away from tents and shanty homes. He also emphasized the importance of more dwellings, parks, shade trees, and sanitation.[23] By the turn of the century, West Palm Beach had electrical and telephone service, a library, a sewer system, a pumping station, and paved roads. The 1900 Census indicated a population of 564. The library was established that year.[7] Charles John Clarke, owner of the Palm Beach Yacht Club, donated the two-story building to be used as the library. Other donations allowed the building to be transported across the Lake Worth Lagoon via barge. The building replaced the reading room at City Park.[24] By 1903, the town council submitted a city charter to the Florida Legislature, which was approved on July 21.[7]  In September, a hurricane made landfall near Fort Lauderdale. As inclement weather conditions began arriving in West Palm Beach, businesses suspended their normal operations and people boarded up buildings, even as strong winds arrived. Many buildings lost their roofs, and much debris, including roofing materials, branches, paper, and driftwood, littered the streets. As northeast winds reached their peak late on September 11 and early on September 12, parts of buildings blew away. In the African-American section of the city, several buildings were destroyed. Just one of the four churches stood after the hurricane.[25] Despite the hurricane, the city continued to grow, with newer businesses and more people arriving.[7] Banyan Street, originally the only location where alcohol was sold, gained an infamous reputation for its brothels, gambling halls, and saloons, which included an incident in 1895 in which Mayor Earman was arrested and charged with public intoxication while accompanying a prostitute. He was acquitted of the charges.[26] By 1904, some local women called Carrie Nation, a radical temperance movement member notorious for attacking alcohol-serving establishments with a hatchet. However, there is no indication of her ravaging the saloons on Banyan Street. During the following years, the road's continuously poor reputation resulted in it being renamed First Street in 1925, which was reverted to Banyan Street in 1989.[26] The city's first fire department building and city hall opened in 1905 at the northeast corner of Datura Street and Poinsetta Street (modern day U.S. Route 1, also known as Dixie Highway). In 1909, Palm Beach County was formed by the Florida State Legislature, carved out of the northern portion of Dade County. West Palm Beach became the county seat. That same year, the West Palm Beach Telephone Company, the area's first telephone service, was incorporated with 65 customers.[7] 1910–1927 According to the 1910 United States Census, the population of West Palm Beach was 1,743. Prior to the 1910s, many African Americans in the area lived in a segregated section of Palm Beach called the "Styx",[7] with an estimated population of 2,000 at its peak. However, between 1910 and 1912, African Americans were evicted from the Styx. Urban legend states that the Styx was burned down by Flager's white laborers, as the shanty town was viewed as an eyesore. However, there is much evidence to refute this theory.[27] Most of the displaced residents relocated to the northern end of West Palm Beach, in neighborhoods today known as Northwest, Pleasant City, and Freshwater.[7] After the passage of the Dick Act in 1903, Florida became the first state to establish its own National Guard. In 1914, a unit was established in West Palm Beach. Personnel from this unit were deployed to the Mexico–United States border from July 1916 to March 1917 and for service in Europe in October 1917.[7] In 1916, a neo-classical county courthouse was opened. Prior to the opening of the courthouse, county business was conducted at a school building located at Clematis Avenue and Poinsettia Street.[7] The building underwent renovations in the 1950s and 1960s.[28] It was used as the county courthouse until a new courthouse opened in 1995. The Board of County Commissioners agreed in 2002 to return the historic courthouse to its original design. Restoration was completed in March 2008 at a cost of just over $18 million. Today, the original courthouse houses the Historical Society of Palm Beach County and the Richard and Pat Johnson Palm Beach County History Museum.[29]  The Palm Beach Post became a daily newspaper in January 1916, after publishing weekly editions since its founding in 1909. Based in West Palm Beach, the paper is the oldest continuously published daily newspaper in the county.[30] As of November 2017, The Palm Beach Post ranked as the fifth largest newspaper by circulation in the state of Florida, behind only the Miami Herald, Sun-Sentinel, Orlando Sentinel, and Tampa Bay Times.[31] The West Palm Beach Canal opened in 1917. The canal stretched from the Lake Worth Lagoon westward to Twenty Mile Bend and then northwestward to Canal Point, where it enters Lake Okeechobee. The canal lowered Lake Okeechobee and allowed land to be drained for agriculture, while also allowing easier transportation of crops to the coast. The city capitalized on this development and built a new canal branch and dock facilities, boat slips, a turning basin, and warehouses. West Palm Beach soon became the county's shopping center for pineapple, sugar cane, and winter vegetables.[7] By the 1910s, a movement to transition to a council–manager government gained enough momentum to allow a vote in 1919. Under the proposal, the citizens would elect members of the city council, who would in turn select the mayor. On August 29, 1919, voters approved the proposal by 201–82. The proposal also called for a primary for the election of city commissioners to be held within three weeks. The rules for the primary stated the top three vote-getters were elected to the city council.[32] David F. Dunkle became the first mayor under this system, with his inauguration occurring on September 22, 1919.[33]  Although construction slowed dramatically during World War I, West Palm Beach and the state of Florida, unlike most of the nation, was not hit as hard by the Post–World War I recession, as the completion of major roadways such as Dixie Highway and the milder climate attracted middle-class tourists. Investors and realtors heavily promoted living and vacationing in Florida. The city grew rapidly in the 1920s as part of the Florida land boom. The population of West Palm Beach quadrupled from 1920 to 1927, coupled with significant growth in businesses and public services. Property values also rose significantly, from $13.6 million in 1920 to $61 million in 1925.[7] All areas of West Palm Beach east of Australian Avenue had been platted by 1927, although sections north of 36th Street and south of Southern Boulevard remained mostly undeveloped.[21]: 13 Many of the city's landmark structures and preserved neighborhoods were constructed in the 1920s. For example, during this time, the Harvey and Clarke architectural firm – formed by Henry Stephen Harvey (the Mayor of West Palm Beach from 1924 to 1926) and L. Philips Clarke in 1921 – designed several structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Alfred J. Comeau House, American National Bank Building, Comeau Building, Dixie Court Hotel (demolished in 1990), Guaranty Building and Pine Ridge Hospital. Several waterfront hotels were built in the 1920s, including the Royal Palm, El Verano, and Pennsylvania. Other notable projects constructed during this era included Good Samaritan Hospital and the Seaboard Airline Railroad Station.[7] Additionally, the city opened its first permanent library on January 26, 1924, named the Memorial Library in honor of those who died during World War I.[34] 1928–1939 The 1928 Okeechobee hurricane devastated West Palm Beach. The city observed at least 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall.[35] Among the buildings destroyed included a furniture store, pharmacy, warehouse, hotel, school, an ironworks,[36] and the fire station.[37] All of the theaters in the city suffered severe damage or destruction.[38] Generally, wood-frame buildings fared poorly and many other structures lost their roofs, while the few concrete-built structures remained standing.[39] Skylights at the county courthouse and city hall shattered, damaging documents and records.[40][41] Only one business on Clematis Street escaped serious damage,[41] while two buildings remained standing on the north side of Banyan Boulevard (then known as First Street) between Dixie Highway and Olive Avenue, owing to the frail construction of the business buildings in that section of the city.[42] The latter, considered the auto row of West Palm Beach, was reduced to "a mass of debris", according to The New York Times.[43] Partially destruction of the hospital led to a temporary hospital being set up in the Pennsylvania Hotel,[44] which itself suffered damage after the chimney crashed through 14 floors.[45] At the city library, more than half of the books were destroyed and the floor was covered with about 2 ft (0.61 m) of water and mud.[46] Waves washed up mounds of sand and debris across Banyan Boulevard, Clematis Street, and Datura Street, to Olive Avenue.[39]  The buildings used by The Palm Beach Post and the Palm Beach Times suffered severe damage, though both companies continued to publish newspapers with little interruption.[47][48][49] The Central Farmers Trust Company, the city's only bank, was deroofed and flooded.[37] Prior to the storm, the American Legion building was designated as the headquarters for the Red Cross, but the building was severely damaged, forcing the Red Cross to relocate its relief post to another building.[42] At Palm Beach High School, then located where the Dreyfoos School of the Arts stands today, the clock tower collapsed.[50] The storm deroofed most buildings at Saint Ann's Catholic Church,[51] while Bradley Hall Towers suffered total destruction.[52] At Flamingo Park, one of the worst hit areas of the city, many homes suffered damage, while a shopping center on Lake Avenue experienced near complete destruction. In contrast, the El Cid and Northwood neighborhoods generally experienced only superficial impact. Fallen pine trees blocked many streets in Vedado. At Bacon Park, the area west of Parker Avenue was desolate.[53]  Many homes also experienced damage in the African-American section of the city, where most dwellings were built of discarded material. On one street, only two houses did not lose either their walls or roof. Strong winds tossed cars and walls down the streets. During the storm, about 100 people ran to a trash incinerator, a concrete-reinforced building.[54] Local Black churches suffered significant damage. Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church lost many bricks on its front facade, much of the metal grillwork around the entrances,[49] and its roof.[55] The storm destroyed Payne Chapel AME Church, while St. Patrick's Catholic Church received about $40,000 in damage.[56] According to county coroner T. M. Rickards, the streets were "shoulder-deep in debris. The suffering throughout was beyond words."[35] Throughout the city, the storm destroyed 1,711 homes and damaged 6,369 others, leaving about 2,100 families homeless. Additionally, the hurricane demolished 268 businesses and impacted 490 others.[36] In all, damage totaled approximately $13.8 million and 11 deaths occurred.[36][47] Farther inland, the hurricane is believed to have killed at least 2,500 people in cities just southeast of Lake Okeechobee, particularly in Bean City, Belle Glade, Chosen, Pahokee, and South Bay.[57] After the storm, at least 743 bodies were brought to West Palm Beach for burial. Due to racial segregation, all but eight of the victims that received a proper burial at Woodlawn Cemetery were white. The remaining 674 bodies who were black or of an unidentifiable race were mass buried at a site near the junction of 25th Street and Tamarind Avenue, which was the city's paupers cemetery. After the burials were complete, Mayor Vincent Oaksmith proclaimed an hour of mourning on October 1 for those who died during the storm. At the pauper's cemetery, a funeral service was hosted by several local clergymen and attended by about 3,000 people, including educator Mary McLeod Bethune. A memorial was placed at Woodlawn Cemetery on behalf of the victims of the storm,[58] but no such marker was placed at the paupers cemetery mass burial site until 2003, around the 75th anniversary of the storm.[59]  The economic decline and the storm combined caused further skepticism among potential investors and buyers of land in the area. As a result, property values plummeted. During the end of the 1920s, several banks and hotels throughout the county declared bankruptcy or were sold to new owners, Palm Beach Bank and Trust. In October 1929, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred, initiating the Great Depression. Real estate costs in West Palm Beach dropped 53 percent to $41.6 million between 1929 and 1930 and further to only $18.2 million by 1935. Twelve banks failed in Palm Beach County by 1930. However, houses continued to be constructed by the private sector.[15] Also in spite of the economic turmoil, the population continued to increase, albeit at a far slower rate than the previous decades. Between 1920 and 1930, the city's population went from 8,659 to 26,610, a 207.3% increase. However, from 1930 to 1940, the population of the city increased from 26,610 to 33,693, or 26.6%.[60] In 1933, Palm Beach Junior College (PBJC) was established in West Palm Beach at Palm Beach High School, which is now Dreyfoos School of the Arts, becoming the first junior college in Florida. County school superintendent Joe Youngblood and Palm Beach High School principal Howell Watkins were instrumental in founding the college. Watkins was selected to be the college's first dean. Initially, the college's goal was to provide additional training to local high school graduates who were unable to find jobs during the Great Depression. The college would move out of its original building in 1948 and later to its current main campus in Lake Worth in 1956. PBJC eventually expanded to five campuses – Belle Glade (1972), Boca Raton (1983),[61] Loxahatchee Groves (2017),[62] and Palm Beach Gardens (1980). The college was renamed Palm Beach Community College in 1988 and then Palm Beach State College in 2010.[61] After learning to fly an airplane in 1932, Grace Morrison began an effort to gain support for a public airport in Palm Beach County. Construction began in the mid-1930s and costed about $180,000 to build. Morrison died in a car accident in Titusville a few months before the airport opened in 1936. In its early years, the airport was called Morrison Field in her honor. The inaugural flight from Morrison Field was piloted by Dick Merrill. Due to poor weather conditions in Pennsylvania, the plane had to crash land near Matamoras.[63] Also in 1936, WJNO-AM 1290 (then WJNO - 1230 AM) signed on, becoming West Palm Beach's first radio station.[64] 1940–1979 During World War II, Florida's long coastline became vulnerable to attack. German U-boats sank dozens of merchant ships and oil tankers just off the coast of Palm Beach, which was under black out conditions to minimize night visibility to German U-boats. The U.S. Army Air Corps (a forerunner of the United States Air Force) established an Air Transport Command post at Morrison Field. The army constructed barracks, hangars, and other buildings to support about 3,000 soldiers. Throughout the course of the war, over 45,000 pilots trained or flew out of the command post, many in preparation for the Normandy landings. The 313th Material Squadron was moved from Miami Municipal Airport to Morrison Field in April 1942, with approximately 1,000 men working around the clock in order to repair and test aircraft before they were put into service. In 1947, Morrison Field was deactivated and returned to the possession of Palm Beach County.[66] Morrison Field was renamed Palm Beach International Airport (PBIA) later that year.[67] Late on August 26, 1949, a Category 4 hurricane made landfall in Lake Worth.[68] In West Palm Beach, the hurricane produced sustained winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) and gusts up to 130 mph (210 km/h) at PBIA.[69] The airport itself suffered about $1 million in damage, with several hangars destroyed and 16 planes ruined and 5 others affected. Additionally, 15 C-46s suffered damage.[70] Throughout West Palm Beach, about 2,000 homes out of about 7,000 in the city were damaged. It was estimated that the hurricane caused more than $4 million in damage in West Palm Beach.[71] As a result of the Korean War, PBIA again became a military post in 1951. Temporarily renamed Palm Beach Air Force Base,[72] nearly 23,000 Air Force personnel trained at the base during the Korean War. The federal government proposed keeping Palm Beach Air Force Base as a permanent military facility, but ultimately decided to return it to Palm Beach County control in 1959, and the name was reverted to Palm Beach International Airport.[73] The 1950s saw another boom in population, partly due to the return of many soldiers and airmen who had served or trained in the area during World War II. Also, the advent of air conditioning encouraged growth, as year-round living in a tropical climate became more acceptable to northerners. West Palm Beach became the nation's fourth fastest growing metropolitan areas during the 1950s; the city's borders spread west of Military Trail and south to Lake Clarke Shores.[74] Between 1949 and 1962, property values rose from $72 million to $147.5 million, while the population in 1950 was 43,612 and increased about 30% by 1960. In 1955, using a $18 million bond issue, the City of West Palm Beach upgraded its sewer system and purchased the water treatment plant (then owned by Henry Flagler's estate) and land to the west of the city's boundaries, including 20 sq mi (52 km2) of wetlands (from Flagler Water Systems) and an additional 17,000 acres (6,900 ha) of land previously owned by Flagler's Model Land Company.[75] About two year later, the city sold about 5,500 acres (2,200 ha) of that land for $4.35 million to Perini Corporation of Massachusetts president Louis R. Perini, Sr. In order to transform the wetlands into dry land, Perini hired Gee and Jensen Engineers, who used approximately 30,000,000 cubic yards (23,000,000 m3) of fill to complete the task. Perini constructed the Roosevelt Estates neighborhood for middle class African-Americans. Additionally, Perini changed the name of 12th Street to Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard and extended it westward. The road was curved southwestward to eventually connect with Okeechobee Boulevard. Perini would also construct the first section of Interstate 95 in Palm Beach County in 1966, from Okeechobee Boulevard to 45th Street.[75]  In the 1960s, Perini sold much of the land back to the city of West Palm Beach. The city, in turn, built West Palm Beach Municipal Stadium in 1963, the West Palm Beach Auditorium in 1965, and the Palm Beach Mall in 1967. On October 26, 1967, the Palm Beach Mall opened along Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard between Interstate 95 and Congress Avenue. The opening ceremony included a ribbon-cutting by Governor Claude Kirk, Mayor Reid Moore Jr., and Miss USA 1967 winner Cheryl Patton. About 40,000 visited the mall on its opening day. Upon opening, the mall contained 87 stores over a 1,000,000 sq ft (93,000 m2) area. The mall gradually began to draw businesses and patrons away from downtown, especially when Burdines left downtown in 1979.[76] The 1950s and 1960s also saw the opening of the Palm Beach Zoo (then known as the Dreher Park Zoo) in 1957 and the South Florida Science Center and Aquarium in 1961.[77][78] The first shopping plaza in Palm Beach County, the Palm Coast Plaza, opened in 1959 along Dixie Highway near the city's southern boundary.[75] At the time, it was considered "the largest and most complete shopping center between Miami and Jacksonville".[79] The city of West Palm Beach opened a new library at the east end of Clematis Street on April 30, 1962, to replace the Memorial Library.[80] In 1968, Palm Beach Atlantic University (PBA), an accredited, private Christian university, began at a downtown local church,[81] before opening a campus in the 1980s.[82] On January 19, 1977, West Palm Beach recorded its first ever snowfall event, as part of a cold wave episode.[83] Snow fell between 6:10 a.m. and 8:40 a.m., but hardly any accumulation was measured, as the snow almost immediately melted or was blown away after touchdown.[84] PBIA also recorded temperatures as low as 27 °F (−3 °C).[83] 1980–1999 By the 1980s, downtown West Palm Beach had become notorious for crime, poverty, and vacant and dilapidated businesses and houses. Then-United States Senator Lawton Chiles referred to the area as a "war zone" during his visit in September 1987, while local politicians were not optimistic about the future of downtown. The city had the highest crime rate for a city of its size in the late 1980s. Crack USA: County Under Siege, a 1989 documentary film about the crack epidemic, was filmed in West Palm Beach.[85] In 1986, private investors David C. Paladino and Henry J. Rolfs presented a 20-year, $433 million project to revitalize the western side of downtown. The proposal included plans 3,700,000 sq ft (340,000 m2) for offices, 1,900,000 sq ft (180,000 m2) for retail stores, 800 hotel rooms, and 700 housing units.[86] Paladino and Rolfs purchased and razed properties across 77 acres (31 ha) of land – more than 300 properties[87] – adjacent to Okeechobee Boulevard for about $40 million,[86] with the exception of First United Methodist Church, which later became the Harriet Himmel Theater.[87] The duo donated 5 acres (2.0 ha) of land for development of the Kravis Center for the Performing Arts, which opened in 1992.[87] However, by the early 1990s, the project was discontinued after Rolfs exhausted his personal fortune and due to defaulted loans, foreclosures, lawsuits, and a recession.[85] After several decades under the Council–manager government, public opinion shifted in favor of electing a strong mayor and having a mayor–council government by the early 1990s. Under one proposal, the mayor would be elected to a four-year term and be eligible for re-election once, the city manager and mayor would share administrative duties, and the mayor would receive the power to veto commission votes, which could be overridden by a 4–1 vote. Additionally, the mayor would be authorized to line-item veto the budget, initiate investigations, and supervise contracts and purchases involving more than $5,000.[88] After a successful petition drive, this proposal would be listed on the ballot as Question 2. In response, the city commission submitted Question 1, which effectively added a weak mayor. In this proposal, the difference versus Question 2 is that the city manager would retain administrative authority, the mayor would vote with city commissioners only in the event of a tie, and the mayor could not veto votes by the city commission.[89] In the referendum for mayor, voters were required to vote yes or no on Question 1 and Question 2. If both received a majority of yes votes, the question with more votes passed. The election was held on March 12, 1991. Both propositions received a majority of the votes. Question 1 received 2,944 yes votes versus 2,665 no votes, a margin of 52.6%–47.4%. Question 2 passed by a margin of 65.7%–34.3% and a vote total of 3,779–1,972. Therefore, Question 2 prevailed, allowing citizens of West Palm Beach to directly elect a strong mayor.[90] The first general election for Mayor of West Palm Beach since the late 1910s occurred on November 5, 1991. Candidates included attorney and former state representative Joel T. Daves III, city senior planner Jim Exline, Nancy M. Graham,[91] Josephine Stenson Grund,[92] property management company owner Michael D. Hyman, and former Palm Beach County commissioner Bill Medlen. Graham and Hyman received 34.3% and 24.9% of the vote, respectively, allowing them to advance to a run-off election held on November 19.[91] Graham defeated Hyman by a margin of 55.8%–44.2%. She was sworn in as the city's first strong mayor on November 21.[93] During the campaign, Graham vowed for improvements to downtown.[93] Much of the renovations in downtown began after a $18.2 million bond was issued to the city in October 1992, with $4 million allotted to the waterfront.[94] Among the first projects was a beautification of Clematis Street, which was complete in December 1993. Over the previous six months, benches, sidewalks, and trees were replaced. The project resulted in several businesses moving to Clematis Street.[95] Architect Dan Kiley was hired for several of the waterfront projects, including building an amphitheater, remodeling the library, and designing an interactive water fountain at Flagler Park.[96]  The plan for building the amphitheater would require the city to spend about $1 million for construction, as well as $171,400 for the demolition of a Holiday Inn. The building was chosen because it had remained vacant and gutted since 1986, while plans for reselling or remodeling the building for a different use fell through. A nearby bank agreed to finance most of the cost of purchasing the building, allowing the city to acquire the hotel for only $1,000.[94] Controlled Demolition, Inc. was hired for the demolition, which was scheduled for December 31, 1993, about 10 seconds before midnight.[97] More than 20,000 people attended the explosion event, which was triggered by about 300 sticks of dynamite.[98] Graham sold $25 tickets for a close-up view of the explosion. Revenue from tickets and donations totaled almost $1 million.[99] Among the most ambitious efforts to rejuvenate economic activity in downtown West Palm Beach was CityPlace. After the city reacquired the land formerly proposed for the Downtown/Uptown project by eminent domain and a multi-million dollar loan in 1995, the city began appealing to large architectural firms to develop the site.[87] Of the three proposed bid, the city commission chose CityPlace by a vote of 5–1 on October 9, 1996.[100] The $375 million project called for an 18 to 24 screen movie theater and a number of restaurants, upscale stores, apartments, and office buildings,[101] all centered around the historical First United Methodist Church,[100] which later became the Harriet Himmel Theatre.[87] Overall, about 2,000,000 sq ft (190,000 m2) of land development was approved. In return, the city agreed to invest $75 million for construction of streets, parking garages, and plazas,[100] with $20 million already borrowed for purchasing land. Construction began in 1998, with stores expected to open in November 1999,[101] though CityPlace would actually open in October 2000.[102] 2000–present CityPlace opened to the public on October 27, 2000, with 31 stores and 1 restaurant opening during the first weekend. Barnes & Noble, Macy's, and a Muvico Parisian 20 and IMAX theater served as the original anchors.[103] The initial focus of CityPlace involved attracting many high-end stores as tenants, though emphasis shifted to home furnishings during the housing bubble. By the Great Recession, the scope turned heavily toward dining and entertainment establishments becoming tenants.[104] Related Companies re-branded CityPlace as "Rosemary Square" in April 2019. The company intends to transform Rosemary Square from a lifestyle center to a more urban-like environment, using $550 million to construct new restaurants, a new mixed-use luxury residential tower, a new hotel, and an office tower containing 300,000 sq ft (28,000 m2) of space. Some asphalt roads were replaced with gray and white pavers and converted to create more pedestrian-walking space.[105] The shopping center was re-named The Square in 2023, then back to CityPlace in 2024. In 2023, the movie theater was demolished; Related Companies intends to construct two office towers in its place and add a 455-seat IMAX theater.[106][107] As the county seat of Palm Beach County, West Palm Beach entered the national spotlight during the 2000 presidential election.[108] According to the results officially certified by Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris, George W. Bush very narrowly carried the state of Florida over Al Gore – by 537 votes. Both candidates needed to win the state of Florida in order to secure at least 270 electoral votes, and thereby prevail in the presidential election.[109] The close results and Palm Beach County's controversial butterfly ballot led to a notorious recount.[108] Among those serving on the canvassing board included former West Palm Beach mayor Carol Roberts.[110] Ultimately, the United States Supreme Court decided in Bush v. Gore on December 12, 2000, that Harris's tally would stand, awarding Bush the 25 electoral votes of Florida and the presidential election.[109]  In 2004 and 2005, several tropical cyclones impacted Palm Beach County, including hurricanes Frances, Jeanne, and Wilma.[108] West Palm Beach was affected most by Hurricane Wilma in October 2005, with the eye passing directly over the city at Category 2 intensity. Wilma produced hurricane-force winds and gusts up to 101 mph (163 km/h) at the Palm Beach International Airport.[111] Throughout the city, 1,194 businesses suffered minor damage and 105 others experienced severe impact, while one was destroyed.[112] A total of 6,036 homes received some degree of damage from the storm, while 16 were completely demolished. Additionally, 20 city government buildings were damaged. Overall, damage in West Palm Beach totaled approximately $425.8 million, with $267.4 million in damage to businesses, $153.1 million to residences, and $5.3 million to public property.[113] In the spring of 2009, City Center opened for business at the corner of Clematis Street and Dixie Highway. Constructed at a cost of approximately $154 million, the complex included a new library and city hall, while several city departments relocated to the complex.[114] The city opened the Mandel Public Library of West Palm Beach on April 13, 2009 at City Center, replacing the original library at the east end of Clematis Street.[115] The original library was demolished later that year for construction of a waterfront park and pavilion, which opened to the public in February 2010.[116] The Mandel Public Library is approximately 2.5 times larger than the former library.[117] The library currently circulates more than 800,000 items and has over 100,000 registered card holders.[118]  The 2010 United States Census counted a population of 99,919 people in West Palm Beach.[1] With the number being just 81 short of 100,000, then-outgoing mayor Lois Frankel indicated the potential for challenging the tally, as having a population of at least 100,000 would entitle the city to additional grants.[119] Additionally, the United States Census Bureau estimated that the city had a population of 100,665 people on April 1, 2010. However, the city government apparently did not challenge the 99,919 population figure, as it remains in the official census records.[1] Although CityPlace revitalized downtown, it also contributed to the demise of the Palm Beach Mall. After a significant decline in foot traffic and tenants,[120] as well as failed attempts to lure big box stores such as Bass Pro and IKEA to the mall,[121] it was demolished in 2013.[122] Palm Beach Outlets, designed and operated by New England Development, opened in February 2014 at the same location. The 460,000 sq ft (43,000 m2) outlet mall, comprising more than 100 stores, is anchored by Saks Fifth Avenue.[123] With the closure of the municipal stadium in 1997 (and its subsequent demolition in 2002), West Palm Beach had lost its ability to host spring training for a Major League Baseball.[124] However, with the opening of the FITTEAM Ballpark of the Palm Beaches in 2017, spring training returned to the city after a 20-year hiatus. The 6,500 seat stadium hosts the spring training events for the Houston Astros and Washington Nationals.[125] In its inaugural year, 55,881 people attended Astros training games. However, in 2018, attendance increased to 67,931 people as a result of the Astros' 2017 World Series championship.[126] The high-speed train Brightline opened its first two stations in Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach in January 2018, with a Miami station opened in May of that year.[127] Brightline extended its service to Orlando in 2023.[128] On September 15, 2024, Donald Trump, a former president of the United States and nominee of the Republican Party in the 2024 presidential election, survived an assassination attempt while golfing at Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach. A suspect, later identified as 58-year-old Ryan Wesley Routh, was spotted hiding in nearby shrubbery while aiming a rifle at a member of Trump's security detail.[129] A Secret Service agent fired upon Routh, who fled the scene and was later captured in Martin County.[130] Officials believe that Routh intended to shoot Trump,[131][132] and Routh was indicted on September 24 on charges of attempting to assassinate a presidential candidate. No injuries were reported. See also

References

Bibliography

External links |