|

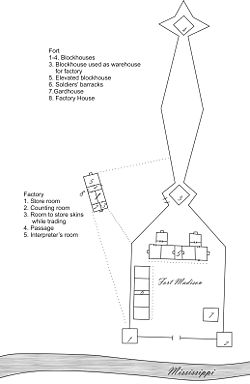

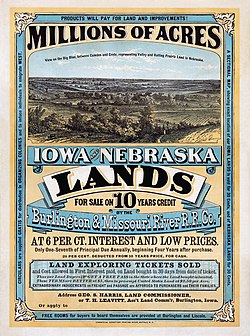

History of IowaNative Americans in the United States have resided in what is now Iowa for thousands of years. The written history of Iowa begins with the proto-historic accounts of Native Americans by explorers such as Marquette and Joliet in the 1680s. Until the early 19th century Iowa was occupied exclusively by Native Americans and a few European traders, with loose political control by France and Spain.[1][2] Iowa became part of the United States of America after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, but uncontested U.S. control over what is now Iowa occurred only after the War of 1812 and after a series of treaties eliminated Indian claims on the state. Beginning in the 1830s Euro-American settlements appeared in the Iowa Territory, U.S. statehood was acquired in 1846, and by 1860 almost the entire state was settled and farmed by Euro-Americans. Subsistence frontier farming was replaced by commodity farming after the construction of railroad networks in the 1850s and 1860s. Iowa contributed many soldiers who fought in the American Civil War. Afterwards they returned to help transform Iowa into an agricultural powerhouse, supplying food to the rest of the nation.[2] The industrialization of agriculture and the emergence of centralized commodities markets in the late 19th and 20th centuries led to a shift towards larger farms and the decline of the small family farm; this was exacerbated during the Great Depression. Industrial production became a larger part of the economy during World War II and the postwar economic boom. In the 1970s and 1980s a series of economic shocks, including the oil crisis, the 1980s farm crisis, and the Early 1980s recession led to the collapse of commodities prices, a decline in rural and state population, and rural flight. Iowa's economy rebounded in the 1990s, emerging as a modern mixed economy dominated by industry, commerce, and finance, in which agriculture is a comparatively small component. Prehistory in Iowa When the American Indians first arrived (in what is now Iowa) thousands of years ago they would hunt and gather living in a Pleistocene glacial landscape. By the time European explorers visited Iowa, American Indians were largely settled farmers with complex economic, social, and political systems. This transformation happened gradually. During the Archaic period (more than 2,800 years ago), American Indians adapted to local environments and ecosystems, slowly becoming more sedentary as populations increased. More than 3,000 years ago, during the Late Archaic period, American Indians in Iowa began utilizing domesticated plants. The subsequent Woodland period saw an increase on the reliance on agriculture and social complexity, with increased use of mounds, ceramics, and specialized subsistence. During the Late Prehistoric period (beginning about A.D. 900) increased use of maize and social changes led to social flourishing and nucleated settlements. The arrival of European trade goods and diseases in the Protohistoric period led to dramatic population shifts and economic and social upheaval, with the arrival of new tribes and early European explorers and traders.[3] Early Historic Native Americans By 1804, there were a number of Native American groups in Iowa: the Sauk (Sac) and Meskwaki (Fox) on the eastern edge of Iowa along the Mississippi; the Ioway along the bank of the Des Moines River; the Otoe, Missouri, and Omaha along the Missouri River, and the Sioux in the Northern and Western parts of the State.[4] Additionally, earlier records indicate the presence of the Illinois in Iowa, though they were nearly gone by the time of the 1804 observations.[5] The total number of these groups in Iowa in 1804 is estimated to be less than 15,000.[4] While these groups generally came initially for food, some of them (e.g., Illinois, Sauk, Meskwaki) immigrated as a result of warfare with other tribes or the French.[6][7] The early and mid-19th century saw the movement of additional groups of Native Americans into Iowa, such as the Potawatomi and Winnebago, followed by the emigration from Iowa of nearly all Native Americans.[8][9] The first European or American to make contact with Native Americans in Iowa is generally considered to be the Frenchmen Louis Joliet and Pere Jacques Marquette, though earlier contact by others is possible.[10] They had set out to discover the Mississippi River, and contacted the Illinois on the eastern side of Iowa in 1673.[11][12] They also were told at that time of the presence of the Sioux along the Missouri.[13] Upon the departure of Joliet and Marquette from the Illinois village, they were accompanied to the riverbank by nearly 600 Illinois, who showed "every possible manifestation of joy," having treated the first Europeans well and offered them peace.[14] Additional exploration by early French, British, and American trappers, traders, explorers, and missionaries informs us of the nature of Native American presence in Iowa from this initial contact in 1673 to the start of settlement by the United States.[15][16]  The Sauk and Meskwaki constituted the largest and most powerful tribes in the Upper Mississippi Valley. They had earlier moved from the Michigan region into Wisconsin and by the 1730s, they had relocated in western Illinois. There they established their villages along the Rock and Mississippi Rivers. They lived in their main villages only for a few months each year. At other times, they traveled throughout western Illinois and eastern Iowa hunting, fishing, and gathering food and materials with which to make domestic articles. Every spring, the two tribes traveled northward into Minnesota where they tapped maple trees and made syrup. Fort Madison was constructed in 1808 to control trade along the Mississippi, and to prevent the reoccupation of the area by the British; Fort Madison was defeated in 1813 by British-allied Indians during the War of 1812 and was the site of Iowa's only true military battle. The Sauk leader Black Hawk first fought against the U.S. at Fort Madison.  In 1829, the federal government informed the two tribes that they must leave their villages in western Illinois and move across the Mississippi River into the Iowa region. The federal government claimed ownership of the Illinois land as a result of Quashquame's Treaty of 1804. The move was made but not without violence. Black Hawk, a highly respected Sauk leader, protested the move and in 1832 returned to reclaim the Illinois village of Saukenuk. For the next three months, the Illinois militia pursued Black Hawk and his band of approximately four hundred Indians northward along the eastern side of the Mississippi River. The Indians surrendered at the Bad Axe River in Wisconsin, their numbers having dwindled to about two hundred. This encounter is known as the Black Hawk War. As punishment for their resistance, the federal government required the Sauk and Meskwaki to relinquish some of their land in eastern Iowa.[17] This land, known as the Black Hawk Purchase, constituted a strip fifty miles wide lying along the Mississippi River, stretching from the Missouri border to approximately Fayette and Clayton Counties in Northeastern Iowa.[18] There were additional cessions by the Sauk and Meskwaki in 1837 (the "Second Black Hawk Purchase") and 1842 (the "New Purchase"), so that by 1845 nearly all had left Iowa.[19][20] Similarly, other Native American groups gave up their Iowa land via treaties with the United States. Western Iowa was ceded by a group of tribes including the Missouri, Omaha, and Oto in 1830.[21] The Ioway ceded the last of their Iowa lands in 1838.[22] The Winnebago and Potawatomi, who had only a short time before been removed to Iowa, were yet again removed and had left Iowa by 1848 and 1846, respectively.[23] The last remaining group, the Sioux, ceded their last Iowa land via an 1851 treaty with the United States, which they completed in 1852.[24][25] Today, Iowa is still home to one American Indian group, the Meskwaki, who reside on the Meskwaki Settlement in Tama County. After most Sauk and Meskwaki members had been removed from the state, some Meskwaki tribal members, along with a few Sauk, returned to hunt and fish in eastern Iowa.[26] The Indians then approached Governor James Grimes with the request that they be allowed to purchase back some of their original land. They collected $735 for their first land purchase and eventually they bought back approximately 3,200 acres (13 km2). After purchasing some of their land back, the Iowa Legislature fought for the Meskwaki tribe to receive an annual payment from the Federal Government. This took ten years to be resolved.[27] Iowa's first Euro-American settlers The Black Hawk Purchase opened up the lands of Iowa to settlers for the first time, and "official" settlement began pursuant to this on June 1, 1833.[18][28] At the time of the opening of these lands, there were likely only 40-50 Americans then settled in Iowa.[29] Many of those who settled before June 1, 1833, were at the Native American villages of Ahwipetuk (now Nashville) and Puckeshetuk (now Keokuk).[30] Many of the pre-1833 settlers were trappers and traders,[31] though some came to mine.[32] The earliest of these Euro-American settlers were French, as the land was originally under French jurisdiction.[33] They came to trade fur, preach, discover mines, and explore, and were generally transient.[34] A few, however, secured land grants and settled in the area when Iowa was under Spanish jurisdiction. The first settler appears to have been Julien Dubuque, a French-Canadian man who arrived at the lead mines near modern-day Dubuque in 1787.[32] He obtained permission to mine the land from the Meskwaki, who generously stated that he could work the mines "as long as he shall please."[35] Additional early Spanish grants include a grant of land near Montrose to Louis Honore in 1799, and of land near McGregor to Basil Giard in 1796.[32] As previously stated, Euro-American settlement in Iowa was generally sparse before the lands opened in 1833. Most of the immigrants who came shortly after this time were from other states, especially Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and to a lesser extent New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the Carolinas.[36] The great majority of newcomers came in family units. Most families had resided in at least one additional state between the time they left their state of birth and the time they arrived in Iowa. Sometimes families had relocated three or four times before they reached Iowa. At the same time, not all settlers remained here; many soon moved on to the Dakotas or other areas in the Great Plains.  The settlers soon discovered an environment different from that which they had known back East. Most northeastern and southeastern states were heavily timbered; settlers there had material for building homes, outbuildings, and fences. Moreover, wood also provided ample fuel. Once past the extreme eastern portion of Iowa, settlers quickly discovered that the state was primarily a prairie or tall grass region. Trees grew abundantly in the extreme eastern and southeastern portions, and along rivers and streams, but elsewhere timber was limited. In most portions of eastern and central Iowa, settlers could find sufficient timber for construction of log cabins, but substitute materials had to be found for fuel and fencing. For fuel, they turned to dried prairie hay, corn cobs, and dried animal droppings. In southern Iowa, early settlers found coal outcroppings along rivers and streams. People moving into northwest Iowa, an area also devoid of trees, constructed sod houses. Some of the early sod house residents wrote in glowing terms about their new quarters, insisting that "soddies" were not only cheap to build but were warm in the winter and cool in the summer. They did not praise the bugs, the smells, or the ever-present dirt, dampness and darkness. Settlers experimented endlessly with substitute fencing materials. Some residents built stone fences; some constructed dirt ridges; others dug ditches. The most successful fencing material was the osage orange hedge until the 1870s when the invention of barbed wire provided farmers with satisfactory fencing material. As the settlers came into Iowa, they naturally established communities. Significant of these were Burlington, Dubuque, Davenport, Keokuk, Fort Madison, and Muscatine.[37] By 1836, when the first census was taken in Iowa, there were 10,531 inhabitants.[38] This rapid immigration was but a sign of things to come. Transportation: Railroad Fever As thousands of settlers poured into Iowa in the mid-19th century, all shared a common concern for the development of adequate transportation. The earliest settlers shipped their agricultural goods down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Louisiana. Steamboats were in widespread use on the Mississippi and major rivers by the 1850s. In the 1850s, Iowans had caught the nation's railroad fever. By 1860, Chicago, Illinois was served by almost a dozen lines and had become the regional hub. Iowans, like other Midwesterners, were anxious to start railroad building in their state. In the early 1850s, city officials in the river communities of Dubuque, Clinton, Davenport, and Burlington began to organize local railroad companies. City officials knew that railroads building west from Chicago would soon reach the Mississippi River opposite the four Iowa cities. With the 1850s, railroad planning took place which eventually resulted in the development of the Illinois Central, the Chicago and North Western Railway, reaching Council Bluffs in 1867. Council Bluffs had been designated as the eastern terminus for the Union Pacific, the railroad that would eventually extend across the western half of the nation and along with the Central Pacific, provide the nation's First transcontinental railroad. A short time later a fifth railroad, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, also completed its line across the state. Steamboat traffic continued on the major rivers. The completion of five railroads across Iowa brought major economic changes. Of primary importance, Iowans could travel every month of the year. During the later 19th and early 20th centuries, even small Iowa towns had six passenger trains a day. Railroads provided year-round transportation for Iowa's farmers. With Chicago's preeminence as a railroad center, the corn, wheat, beef, and pork raised by Iowa's farmers could be shipped through Chicago, to markets in the U.S. and worldwide. Railroads made industry possible. Before 1870, Iowa contained some manufacturing firms in river towns. Most new industry were based on food processing or farm machinery. In Cedar Rapids, John and Robert Stuart, along with their cousin, George Douglas, started an oats processing plant. In time, this firm took the name Quaker Oats. Meat packing plants also appeared in the 1870s in different parts of the state: Sinclair Meat Packing opened in Cedar Rapids, Booge and Company started in Sioux City, and John Morrell & Company set up operations in Ottumwa. The railroads also created a significant demand for coal. Coal mines were quickly opened and expanded wherever the new railroads passed through areas with coal exposures. The Chicago and North Western Railway encouraged development of mines in Boone and Moingona. The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway encouraged similar development in Mystic, Iowa and neighboring coal camps. Where railroads did not have direct access to sufficient coal, long branch lines were built into the coal fields. The Burlington, Cedar Rapids and Northern Railway built a 66-mile branch to What Cheer in 1879,[39] and the Chicago and North Western built a 64-mile branch to its mines in Muchakinock in 1884.[40] By 1899, Iowa's coal mines employed 11,029 men to produce almost 5 million tons of coal per year.[41] In 1919, Iowa had about 240 coal mines that between them produced over 8 million tons of coal per year and employed about 15,000 men.[42] American Civil WarIowa became a state on December 28, 1846 (the 29th state), and the state continued to attract many settlers, both native and foreign-born. Only the extreme northwestern part of the state remained a frontier area. Iowa supported the Union during the American Civil War, voting heavily for Lincoln and the Republicans, though there was a strong antiwar "Copperhead" movement among settlers of Southerner origins and among Catholics. There were no battles in the state, but Iowa sent large supplies of food to the armies and the eastern cities. More than 75,000 Iowans served, many in combat units attached to the western armies. 13,001 died of wounds or (two-thirds) of disease. Eight thousand five hundred Iowans were wounded. The draft was not used in Iowa during the Civil War because Iowa had twelve thousand more men serving than the draft called for. Political arena of late 19th through early 20th centuryThe Civil War era brought considerable change to Iowa and perhaps one of the most visible changes came in the political arena. During the 1840s, most Iowans voted Democratic although the state also contained some Whigs. During the 1850s, however, the state's Democratic Party developed serious internal problems as well as being unsuccessful in getting the national Democratic Party to respond to their needs. Iowans soon turned to the newly emerging Republican Party. The new party opposed slavery and promoted land ownership, banking, and railroads. The political career of James Grimes illustrates this change. In 1854, Iowans elected Grimes governor on the Whig ticket. Two years later, Iowans elected Grimes governor on the Republican ticket. Grimes would later serve as a Republican United States Senator from Iowa. Republicans took over state politics in the 1850s and quickly instigated several changes. They moved the state capital from Iowa City to Des Moines, established the University of Iowa and they wrote a new state constitution. During the Civil War, many Democrats supported the anti-war Copperhead movement. From the late 1850s until well into the 20th century, Iowans remained largely Republican. Only once, in 1889, did Democrats elect a governor, Horace Boies who was reelected in 1891. Their secret was winning increased support from the "wet" (anti-prohibition) Germans. Historically, the Democrats were strongest in German areas, especially along the Mississippi River. Thus, the German Catholic city of Dubuque continues to be a Democratic stronghold. Meanwhile, the Yankees and Scandinavians (and Quakers) were overwhelmingly Republican.[43] Several Republicans took leadership positions in Washington, particularly Senators William Boyd Allison, Jonathan P. Dolliver, and Albert Baird Cummins, as well as Speaker of the House David B. Henderson.  Progressive movementThe spirit of progressivism emerged in the 1890s, flourished in the 1900s, and decayed after 1917.[44] Under the guidance of Governor (1902–1908) and Senator (1908–1926) Albert Baird Cummins the "Iowa Idea" played a major role in state and national progressivism. A leading Republican, Cummins fought to break up monopolies. His Iowa successes included establishing the direct primary to allow voters to select candidates instead of bosses; outlawing free railroad passes for politicians; imposing a two-cents per mile railway maximum passenger fare; imposing pure food and drug laws; and abolishing corporate campaign contributions. He tried, without success, to lower the high protective tariff in Washington.[45][46]  Women put women's suffrage on the state agenda. It was led by local chapters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, whose main goal was to impose prohibition. In keeping with the general reform mood of the latter 1860s and 1870s, the issue first received serious consideration when both houses of the General Assembly passed a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution in 1870. Two years later, however, when the legislature had to consider the amendment again before it could be submitted to the general electorate. It was defeated because interest had waned, and strong opposition had developed especially in the German-American community, which feared women would impose prohibition. Finally, in 1920, Iowa got woman suffrage with the rest of the country by the 19th amendment to the federal Constitution.[47] Iowa: Home for Immigrants As the cession of Native American lands in Iowa continued, settlement by the United States pushed further westward. By 1838 there were 22,859 people in Iowa, and 42,112 by 1840.[48] One interesting occasion illustrating the westward push occurred on April 30, 1843.[49] Much of the land in central Iowa had been ceded from the Native Americans to the United States pursuant to the "New Purchase" in 1842.[50] As the date at which settlement would be allowed approached, settlers gathered at the border to these new lands.[49] On April 30, 1843, a cannon sounded at midnight, after which the settlers pushed into the new lands and settled many areas by sunrise.[49] Most of the settlers who came into these "New Purchase" lands were from Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri, and to a lesser extent Wisconsin, Virginia, and Pennsylvania.[51] Notable during the 1840s was the arrival of the Norwegians in 1840,[52] Swedes in 1845,[53] and Dutch in 1847.[54] By 1850, there were 192,214 people living in Iowa.[55] Nearly 90% of the population at this time was from America, with Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania contributing the most settlers.[32][56] Though immigration from other parts of the world had not yet hit full stride, there nonetheless existed 20,969 foreign immigrants in 1850.[56] The largest group was the Germans with over 7,000, followed by the Irish with 4,885, England with 3,785, Canada with 1,756, the Netherlands with 1,108, 712 from Scotland, 361 from Norway, 231 from Sweden, and 19 from Denmark.[56] Czechs also comprised a large settlement group. Settlement patterns to this point generally were in the southern and eastern parts of the state,[57] often near the rivers.[58] Immigration during this time was affected by many things, notably: the completion of railroads to the Mississippi, the advertising of Iowa lands by railroad and steamship companies, the publication of favorable guides and articles, drought in the Ohio Valley, and a cholera epidemic in other states.[59][60] One fine example of a guide is John B. Newhall's Sketches of Iowa: Or, The Emigrant's Guide,[61] written in 1841 for prospective British emigrants.[62] Additional examples include Nathan Parker's Iowa as it is in 1855: a Gazetteer for Citizens, and a Handbook for Immigrants[63] and John Taylor's Iowa: the "Great Hunting Ground" of the Indian; and the "Beautiful Land" of the White Man: Information for Immigrants.[64] Other factors affecting immigration were frequently religious and political oppression in the immigrant's homeland,[65][66] as well as economic problems in the homeland.[66] While nativism was strong in other states, Iowa wanted immigrants and resisted the Know-Nothing Party.[67] Utopians came to Iowa in the 1850s to start the communistic colonies of Icaria, Amana, and New Buda, where property was held in common.[68] Icaria was a French colony settled near Corning, Iowa, in 1858. The goal of the Icarian settlers was to live in accordance with the ideas of Etienne Cabet as a purely socialist community.[69] Amana was a religious colony formed by German pietists in 1855 that practiced communism until 1932. It then became a center of modern manufacturing, especially of household appliances.[70] New Buda was a proposed colony by a group of defeated Hungarian revolutionaries who arrived in Iowa in 1850, but was never built.[71] Immigration to Iowa continued to accelerate throughout the remainder of the 19th century, peaking in 1890.[65] Immigration of foreign-born persons was no exception. In 1860, 106,081 of the 674,913 people living in Iowa were foreign-born persons.[72] Most were German or Irish, though there were many from the rest of the United Kingdom, as well as Norway and Sweden.[72] African-Americans also began immigrating to Iowa in more significant numbers through the 1860s, going from 1,069 inhabitants in 1860 to 5,762 in 1870.[73] The 1870s saw 204,692 foreign-born immigrants in Iowa, with 261,650 and 324,069 in 1880 and 1890, respectively.[65] Competition among the states for immigrants was increasing during this time, leading Iowa to take certain measures to attract immigrants.[74] The Iowa State Board of Immigration was created in 1870, and began printing promotional materials.[74] One notable booklet was entitled Iowa: The Home of Immigrants.[75] The publication gave physical, social, educational, and political descriptions of Iowa. The legislature instructed that the booklet be published in English, German,[76] Dutch, Swedish, and Danish.[77] The tide of foreign immigration receded, so that many groups had largely stopped coming by the beginning of the 20th century.[65] Some, however, were just starting to immigrate. Southern and Eastern European immigration, especially from Italy and Croatia, began in not insignificant amounts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as they came to work in Iowan coal mines.[65][78] The early 20th century also saw the start of steady immigration from Mexico,[65] and the mid-1970s saw immigration from Southeast Asia (especially the Tai Dam, Vietnamese, and Lao)[79] as refugees from the Vietnam War searched for a peaceful place to live.[65] Immigration patternsDutchThe Dutch came to Iowa in 1847 while under the leadership of Reverend Hendrik (Henry) Pieter Scholte.[54][66] There are several reasons for their immigration. Many did not like the new leadership of the Netherlands under William I.[68] Economic conditions were poor in their homeland,[66] worsened by a potato crop failure[80] There was also a desire to obtain religious freedom, after having been treated poorly on account of religion in their home country.[81] It is likely the latter motivation that led them to name their first Iowan colony Pella, in reference to a religious place of refuge.[82] Once initially established, letters from early Dutch immigrants were published and circulated in the Netherlands, increasing subsequent immigration. A fine example of this is an 1848 piece[83] by Scholte himself, Eene Stem uit Pelle (A Voice from Pella).[81] Additional Dutch immigration continued to Pella, and in the following years a daughter colony was founded at Orange City.[84] ScandinavianScandinavian immigration to Iowa mostly consists of Norwegians and Swedes, though there was a small Danish immigration movement as well. Norwegians generally went to the northern parts of the state, Danes to the south, and Swedes in between.[65][84] The immigration of Scandinavians to Iowa began in significant numbers in the 1850s, and accelerated through the 1890s.[85] Specifically, there were 611 in the state in 1850, 7814 in 1860, 31,177 in 1870, 46,046 in 1880, and 72,873 by 1890.[85] Central causes for their immigration included the following: Economic problems in the homeland (crop failures, low wages, unemployment), dissatisfaction with church and state, letters from previous immigrants, and promotional material from states.[66] Swedish settlement in Iowa began with New Sweden in 1845 and Burlington in 1846.[86] This was followed in the 1860s by settlement in the central portions of the state.[87] The first colony, New Sweden, was led by Pehr Cassel.[88] They had intended on going to one of the first U.S. Swedish settlements at Pine Lake, Wisconsin, but were convinced by Pehr Dahlberg at New York to travel to Iowa instead.[89] Norwegian immigration to Iowa began in 1840[52] with settlement at Sugar Creek[90] in southeastern Iowa, and continued with immigration to northern Iowa in the late 1840s.[91] The Sugar Creek colony in Lee County was the result of a failed Missouri colony, and has its origins in the second Norwegian colony in the United States, that of Fox River in La Salle County, Illinois.[92] The northern Iowa settlements extended from Allamakee and Clayton counties to Winnebago county, and came largely from settlements at Rock County, Wisconsin, Dane County, Wisconsin, and Boone County, Illinois.[93] From the late 1850s through the 1880s, Norwegians pushed to the western portions of the state.[94] By the early 1890s, Norwegian immigration to Iowa had dropped off.[94] CzechMost Czechs in Iowa settled in Cedar Rapids. During the 1850s, Iowa's Czech population became substantial; when the town was reincorporated in 1856, a quarter of its roughly 1,600 inhabitants were Czech immigrants. The availability of cheap land in the new state of Iowa happened to coincide with the Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire that caused a large number of Czechs to flee their homeland and emigrate to the U.S. Today, Cedar Rapids' Czech Village and the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library celebrate the area's Czech heritage. LatinoThe first Latino group to immigrate to Iowa were Mexicans, who can be traced in small numbers to the 1850 census.[95][96] Substantial Mexican immigration, however, did not begin until the early 1900s. In 1900 there were 29 Mexicans in Iowa, followed by 509 in 1910, and 2,560 in 1920.[95] Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and others from Central and South America followed, though a significant majority of Iowa's Latino population was and remains Mexican.[96] The sharp increase in Mexican immigration in the early 20th century has several causes, mostly economic. Sugar consumption was on the rise nationally, and technological breakthroughs in the sugar beet industry allowed Midwestern farms to expand in attempt to meet that need.[97] As they expanded, the need for labor increased.[98] Sugar beet growing requires a significant amount of difficult manual labor, and immigration restrictions on Europeans during the time limited their availability to work in the United States.[98] Additionally, Mexican labor was desired because of their strong work ethic and acceptance of lower wages.[98] Consequently, Mexicans were recruited by the American Beet Sugar Company (American Crystal Sugar Company) from Mexico and the southwestern states to work in the north central part of the state, especially around Mason City.[99] For many of the same reasons that Mexicans were recruited to work in the sugar beet industry, they were also recruited to work on the railroads in Iowa.[100] Many of the Mexicans recruited to work on the railroads established communities at Fort Madison, Council Bluffs, Des Moines, and Davenport.[101] Additionally, a significant revolution in Mexico in 1910 led more Mexicans to emigrate, and ultimately arrive in Iowa.[98] Mexican immigration dropped off during the great depression as the economy weakened, and remained relatively low even into the latter half of the 20th century.[65][102] The late 1980s and subsequent periods have brought a resurgence of Mexican immigration as the demand for labor in the food processing industry has increased.[103] African-AmericanThough African-Americans began immigrating to Iowa in more significant numbers through the 1860s after obtaining freedom,[104] some of the earliest immigrants would have been brought in as slaves by settlers from southern states after the Black Hawk Purchase, despite the fact that slavery never officially existed in Iowa.[105] The absence of legally sanctioned slavery in Iowa did not mean that the state was free from discrimination, however. An 1838 Act[106] prevented African-American settlement in Iowa unless he or she could present a "fair certificate" of "actual freedom" under the seal of a judge and give a $500 bond.[107] Though this undoubtedly slowed African-American immigration, a few immigrants nonetheless came in the 1840s; most worked in the mines of Dubuque or in the river towns.[108] Frequently, they came to be free of slavery.[109] The third general assembly passed an act in 1851 similar to that of the 1839 act, but it appears to have rarely been enforced and was ultimately ruled in 1863 to be unconstitutional.[110] Initial African-American settlement in Iowa after the Civil War was in agricultural communities near the southern border, as well as along river towns on the Mississippi and to a lesser extent the Missouri.[111] Polk County was also a destination for immigrants.[73] Those along the river often worked on boats, though many worked on the railroads and in the lead mines of Dubuque.[112] Over time, African Americans migrated from agricultural communities to urban areas, and from the river towns to the coal mines of southern Iowa.[113] This urban shift started around 1870, while the coal mining shift started in 1880.[113] The coal mining shift began when African-Americans were brought from the southern states to the southern Iowa coal mines as strikebreakers, after which they remained employed there.[114] This immigration was augmented by poor economic conditions in the southern states resulting from discrimination, flood and pest-induced crop failures, and disadvantaged post-reconstruction economic arrangements like sharecropping.[115] The relatively significant African-American immigration to the southern Iowa coal fields led to largely African-American settlements such as Buxton.[116] The first World War brought more African-American immigrants to Iowa, as Fort Des Moines had been designated as "the only camp in the United States for the training of [African American] officers," followed by Camp Dodge near Des Moines.[117] Many came to train in the service of their country, where some remained and brought family and friends from the southern states.[118] This pattern was repeated in World War II, as Fort Des Moines again trained many African Americans.[119] 1917–1945In 1917, the United States entered World War I and farmers as well as all Iowans experienced a wartime economy. For farmers, the change was significant. Since the beginning of the war in 1914, Iowa farmers had experienced economic prosperity. Along with farmers everywhere, they were urged to be patriotic by increasing their production. Farmers purchased more land and raised more corn, beef, and pork for the war effort. It seemed that no one could lose as farmers expanded their operations, made more money, and at the same time, helped the Allied war effort. After the war, however, Iowa farmers soon saw wartime farm subsidies eliminated. Beginning in 1920, many farmers had difficulty making the payment for debts they had incurred during the war. The 1920s were a time of hardship for Iowa's farm families and for many families, these hardships carried over into the 1930s. As economic difficulties worsened, Iowa farmers sought to find local solutions. Faced with extremely low farm prices, including corn at ten cents a bushel and pork at three cents a pound, some farmers in western Iowa formed the Farmers Holiday Association.[120] This group, which had its greatest strength in the area around Sioux City, tried to withhold farm products from markets. They believed this practice would force up farm prices. The Farm Holiday Association had only limited success as many farmers did not cooperate and the withholding itself did little to raise prices. Farmers experienced little relief until 1933 when the federal government, as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, created a federal farm aid program. In 1933, native Iowan Henry A. Wallace went to Washington as Secretary of Agriculture and served as principal architect for the new farm program. Wallace, former editor of the Midwest's leading farm journal, Wallace's Farmer, believed that prosperity would return to the agricultural sector only if agricultural production was curtailed. Further, he believed that farmers would be monetarily compensated for withholding agricultural land from production. These two principles were incorporated into the Agricultural Adjustment Act passed in 1933. Iowa farmers experienced some recovery as a result of the legislation but like all Iowans, they did not experience total recovery until the 1940s. Iowa's only Nobel Peace Prize Winner, Norman Borlaug, was launched in his researches in plant genomics by funding and research through Iowa State University developing strains of rice in Mexico and which emanated from the work of Henry Wallace. Wallace and Borlaug's work helped create the now internationally significant agricultural concern Pioneer Hi-Bred, now a division of DuPont.[121][122] 1945 to presentSince World War II, Iowans have continued to undergo considerable economic, political, and social change. In the political area, Iowans experienced a major change in the 1960s when liquor by the drink came into effect. During both the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Iowans had strongly supported prohibition, but, in 1933, with the repeal of national prohibition, Iowans established a state liquor commission. This group was charged with control and regulation of Iowa's liquor sales. From 1933 until the early 1960s, Iowans could purchase packaged liquor only. In the 1970s, Iowans witnessed a reapportionment of the General Assembly, achieved only after a long struggle for an equitably apportioned state legislature. Another major political change was in regard to voting. By the mid-1950s, Iowa had developed a fairly competitive two-party structure, ending almost one hundred years of Republican domination within the state. In the economic sector, Iowa also has undergone considerable change. Beginning with the first farm-related industries developed in the 1870s, Iowa has experienced a gradual increase in the number of business and manufacturing operations. The period since World War II has witnessed a particular increase in manufacturing operations. While agriculture continues to be the state's dominant industry, Iowans also produce a wide variety of products including refrigerators, washing machines, fountain pens, farm implements, and food products that are shipped around the world. See also

References

Further reading

External links

|