|

History of Anchorage, Alaska

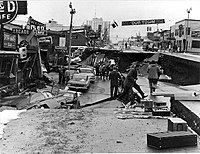

After congress approved the completion of the Alaska Railroad from Seward to Fairbanks in 1914, it was decided that a new town should be built as a port and rail hub along the route. The decision was made to develop a site near Ship Creek on Cook Inlet. Survey parties visited the area in 1914 and researched possible routes for the rails and options for siting the new town. Anchorage was originally settled as a tent city near the mouth of Ship Creek in 1915, and a planned townsite was platted alongside the bluff to the south. Anchorage was mostly a company town for the Alaska Railroad for its first several decades of existence. The strategic location of Alaska, which led to a massive buildup of military facilities throughout Alaska during the years of World War II, changed that. Largely due to the military presence and resource development activities throughout Alaska, Anchorage has enjoyed significant boosts to its population and economic base from 1940 to the present. The 1964 Alaska earthquake outright destroyed or caused significant damage to most of the Anchorage neighborhoods adjacent to Knik Arm, including its downtown. The community rapidly rebuilt, and has since emerged as a major American city. Early historyAccording to archaeological evidence discovered at Beluga Point along the Turnagain Arm, just south of modern-day Anchorage, the Cook Inlet had been inhabited, at least seasonally, by Alutiiq Eskimos beginning between 5000 and 6000 years ago. This occupation occurred in three separate waves, with the second occurring roughly 4000 years ago, and the last around 2000 years ago. The Chugach Alutiiq likely inhabited the area from the first century until sometime between 500 and 1650 AD, when tribes of Dena'ina Athabaskans moved into the area from the interior of the state. Like their Apache cousins, the Dena'ina were a nomadic people, who had no permanent settlements but instead migrated throughout the area following the seasonal resources. In summer they tended to fish along coastal streams and rivers, living in portable, dome-shaped tents constructed out of local willow or birch branches and covered with animal skins. In the fall they would carry these to higher ground where they would hunt moose, Dall sheep, and mountain goats, and late fall was reserved for berry picking. In the winter they would build temporary structures near junction points along common trading routes, and traded with other tribes from areas nearby.[1] Native tribes were not isolated from each other, and trade between the various tribes was common, as well as conflicts and even wars, which often resulted in both sides taking slaves.[2] The Dena'ina learned to make and use kayaks from the Chugach, suggesting that for a time both peoples shared the area.[3] Cook's expeditionWhen Captain James Cook mapped the area in May of 1778, the Chugach people had already abandoned it. On a mission to find the legendary Northwest Passage, Cook was under orders to avoid any obvious rivers or inlets. Upon first sighting the inlet, and the mountains surrounding it on all sides, Cook planned to pass it by, but at the urging of John Gore and many others of his crew, he decided to explore the area in order to assuage his men. For a period of ten days, Cook made an extensive survey of the inlet, which at its head split into two arms. Under a bluff near the mouth of Ship Creek, Cook anchored his ship, HMS Resolution, and had his first encounter with the local Natives as two men approached in kayaks, beckoning them ashore. He sent William Bligh in a boat to scout the north arm, where he met with some local Natives who told him the arm only led to two rivers, called the Knik and Matanuska Rivers. Cook sailed south to scout the other arm, but was unable to sail down it against the strong tides and ran aground on a sandbar while trying to get back out, and had to wait for high tide. Described by George Vancouver as being in a "foul mood", Cook called the arm "River Turnagain". Cook then sailed back to retrieve Bligh, and before leaving he sent James King ashore with a Union Jack to claim the region for King George III. There, King met with some friendly Natives, where they shared some bottles of wine, and gave a toast to King. King gave them the empty bottles, except one, which he stuffed with some papers and buried under a tree where he said, "...in many ages hence it may puzle antiquarians." As Cook sailed away, many Natives stood along the shores of the inlet waving skins or spreading their arms wide in gestures of peace. Cook remarked that the Natives of the area seemed very honest, being only interested in fair trade. He noted that many of them had iron knives or spearheads, surmising that other traders, possibly Russian, had been there before. Cook never gave the inlet a name, although King referred to it as the "Great River". Years later, John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich in London, changed the name to "Cook's River".[4] In 1792, George Vancouver returned and more thoroughly mapped the area, renaming it Cook Inlet, complaining of Cook's voyage that, had they simply stayed for one more day, they could have finished the map and avoided a decade of speculation.[5] Russian occupationRussian presence in south central Alaska was well established in the 19th century. Russian presence in the Cook Inlet was not as extensive as in the Aleutian Islands or the panhandles. The Shelekhov-Golikov Company placed a trading post at Niteh, on a delta between the Knik and Matanuska Rivers. Fierce competition ensued between them and the rival Lebedev-Lastochkin Company, which had two posts farther south along the inlet. Facing financial difficulties, Tsar Paul I gave Shelekhov-Golikov sole monopoly over Alaskan trade, under the direction of Alexander Baranov, which became the Russian-American Company. In 1849, the Russians sent a mining engineer to survey the area, who found small amounts of gold and deposits of coal nearby. By 1850, the former employees of the company had created a small agricultural community in nearby Eklutna, and a Russian Orthodox church was built at Knik. By the late 1860s, it had become apparent that, due to other problems in Europe and Asia, Russia could no longer afford to keep up its enterprises in Alaska, and the company was sold to its employees, becoming the Northern Commercial Company, and then the Alaska Commercial Company.[6] In 1867, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward brokered a deal to purchase Alaska from a debt-ridden Imperial Russia for $7.2 million – about two cents an acre.[7] The deal was lampooned by fellow politicians and by the public as "Seward's folly", "Seward's icebox" and "Walrussia." Gold rushBy 1888, gold was discovered along Turnagain Arm at Resurrection Creek, and the small towns of Hope and Sunrise formed. As a new influx of prospectors flooded the area, small amounts of gold were found in several of the other fjords, and small communities such as Indian, Girdwood, and Portage began to spring up in nearly every one. Lumber and coal were quickly needed, which were imported from the Matanuska Valley, and Joe Spenard constructed a lumber mill that was to become the town of Spenard, just south of modern downtown Anchorage. The fur trade was still a profitable enterprise, and many of the mountain ranges formed natural funnels leading to the Cook Inlet, along a variety of trails that had been used for centuries by Native tribes. With deposits of coal and vast growths of lumber in the Matanuska and Susitna Valleys, and dog sleds packed with gold arriving from strikes in places like Iditarod, population began to rise in these areas and producers were in need of a way to get their goods to market. In Knik, a shipping town formed and grew rapidly, and George W. Palmer opened a general store. The town boasted a restaurant, two hotels, and the first post office in the area. The waters near Knik were too shallow for anything but small boats, so goods had to be ferried to and from larger ships waiting in the deeper waters at the bluff just north of Ship Creek, which became known as the Knik Anchorage.[8] In 1912, Alaska became an organized incorporated United States territory.[9] Alaska Railroad In 1914, congress passed the Alaska Railroad Act, and the Secretary of the Interior formed the Alaska Engineering Commission, consisting of Thomas Riggs Jr., William C. Edes, and Frederick Mears.The commission hired several survey teams who spent the summer scouting possible routes for a railroad, primarily to bring coal from the mines in Matanuska and Healy to a deep-water port. Rumors began to spread before a finding was ever made, and people quickly began to settle in the Ship Creek area, and the name "Knik Anchorage" began to be published in many sources. The commission mapped out three possible routes and submitted them to President Woodrow Wilson. On April 10, 1915, Wilson chose the "Susitna route", from the northern coal-mines in Nenana, deep in the interior of Alaska near Fairbanks, south to Healy and then to the Matanuska coal mines, and down through the Kenai Peninsula to the town of Seward; a deep-water port relatively free of ice where the coal could be loaded onto large bulk carrier ships. In the middle of these end points was the Knik Anchorage, which served as the starting point for construction to begin, proceeding in both directions, and became the headquarters for the commission. As news spread of the prospect of work, a new stampede of people flocked to the Knik Anchorage. Mears arrived to find over 2000 people living on the flats surrounding Ship Creek in ragged tents and makeshift shelters, and unsanitary conditions starting to develop. In addition, as many as 100 people continued to arrive each week. Mears requested that a town site be mapped out above the higher bluffs south of the creek, and President Wilson signed the order later that year, under the provision that the new town become a model of sobriety. To ensure this, an experimental plan was put into place where land was auctioned off to the people but could be forfeited if a person was caught violating the alcohol laws. The waters near Ship Creek, although not a deep-water port, were deep enough for barges and small ships, and a dock was constructed for offloading cargo and railroad supplies. As Knik Anchorage grew, the town of Knik dwindled and finally became a ghost town. The post office moved to the Knik Anchorage, who shortened the name to simply "Anchorage", deeming that all packages and letters should be addressed accordingly. However, in August the people were given a chance to vote on the name, and many options were tossed about, including "Matanuska", "Ship Creek", "Homestead", "Terminal", and "Gateway". The name "Alaska City" won the vote, but the federal government ultimately declined the request.[10] StatehoodBetween the 1930s and 1950s, air transportation became increasingly important. In 1930, Merrill Field replaced the city's original "Park Strip" landing field. By the mid-1930s, Merrill Field was one of the busiest civilian airports in the United States. On December 10, 1951, Anchorage International Airport opened, with transpolar airline traffic flying between Europe and Asia.[9] Starting in the 1940s, military presence in Alaska was also greatly expanded. Elmendorf Air Force Base and Fort Richardson were constructed, and Anchorage became the headquarters of the Alaska Defense Command. Heavy military investment occurred during World War II, due to the threat of Japanese invasion, and continued into 1950, because of Cold War tensions.[9] In the 1940s and 1950s, Anchorage began looking more like a city. Between 1940 and 1951, Anchorage's population increased from 3,000 to 47,000. Crime and the cost of living in the city also grew. In 1949, the first traffic lights were installed on Fourth Avenue. In 1951, the Seward Highway was opened. KTVA, the city's first television station, began broadcasting in 1953. In 1954, Alyeska Resort was established.[9] On January 3, 1959, Alaska joined the union as the 49th state. Soon after, Anchorage faced a severe housing shortage, which was solved partially by suburban expansion.[11][incomplete short citation] In January 1964, Anchorage became a City and Borough.[12] Anchorage also has unsuccessfully bid for the Winter Olympic Games several times, with the most recent being in 1994. Growth and development On March 27, 1964, Anchorage was hit by the Good Friday earthquake, which caused significant destruction.[13][14] The magnitude 9.2 earthquake was the largest ever recorded in North America, and Anchorage lay only 75 miles (121 km) from its epicenter.[13][14] The earthquake killed 115 people in Alaska, and damage was estimated at over $300 million ($1.8 billion in 2007 U.S. dollars).[13][14] It was the second largest earthquake in the recorded history of the world.[13][14] Anchorage's recovery from the earthquake dominated life in the late 1960s. In 1968, oil was discovered in Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Slope; a 1969 oil lease sale brought billions of dollars to the state. In 1974, construction began on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. The pipeline was completed in 1977 at a cost of more than $8 billion. The oil discovery and pipeline construction fueled a boom when oil and construction companies set up headquarters in Anchorage. The Anchorage International Airport also boomed as well, and Anchorage marketed itself as the "Air Crossroads of the World," due to its geographical location.[9]  In 1975, the city and borough consolidated, forming a unified government. Also included in this unification were Eagle River, Eklutna, Girdwood, Glen Alps, and several other communities. The unified area became officially known as the municipality of Anchorage.[15] By 1980, the population of Anchorage had increased to 184,775.[9] The decade of the 1980s started as a time of growth, thanks to a flood of North Slope oil revenue into the state treasury. Capital projects and an aggressive beautification program, combined with far-sighted community planning, greatly increased infrastructure and quality of life. Major improvements included a new library, a civic center, a sports arena, a performing arts center, Hilltop Ski Area, and Kincaid Outdoor Center.[9] The 1980s oil glut lead to an economic recession in Anchorage.[16] Recent historyOn July 8, 2000, the airport was renamed Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport in honor of Alaska's longest-serving senator.[7] Although development is filling available space in the "Anchorage bowl"—a local moniker for the city area—significant undeveloped areas still remain, as well as large areas of dedicated parks and greenbelts. On November 30, 2018, Anchorage experienced a 7.0 magnitude quake, as well as numerous aftershocks. Some buildings and roadways were damaged, and communication and other services were partially disrupted, but no fatalities were reported. The quake, centered about five miles north of the city, was the largest to shake the area since the massive 1964 quake. A tsunami warning was issued and later withdrawn. [17][18] See alsoReferences

Sources

External links

|