|

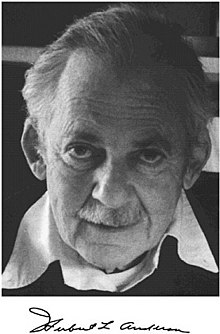

Herbert L. Anderson

Herbert Lawrence Anderson (May 24, 1914 – July 16, 1988) was an American nuclear physicist who was Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago. He contributed to the Manhattan Project. He was also a member of the team which made the first demonstration of nuclear fission in the United States, in the basement of Pupin Hall at Columbia University. He participated in the first atomic bomb test, codenamed Trinity. After the close of World War II, he was a professor of physics at the University of Chicago until his retirement in 1982. There, he helped Fermi establish the Enrico Fermi Institute and was its director from 1958 to 1962. The latter part of his career was as a senior fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory. He was a recipient of the Enrico Fermi Award. EducationBorn in New York City, to a Jewish family. Anderson's lineage to Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, the Maharam of Padua, is detailed in The Unbroken Chain.[1] Anderson earned three degrees at Columbia University, a Bachelor of Arts in 1931,[2] a Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering in 1935, and a PhD in physics in 1940.[3] John R. Dunning, professor of physics at Columbia, closely followed the work of Ernest Lawrence on the cyclotron. Dunning wanted a more powerful neutron source and the cyclotron appeared as an attractive tool to achieve this. During 1935 and 1936, he constructed a cyclotron using many salvaged parts to reduce costs, and with funding from industrial and private donations. The cyclotron project began as Anderson was completing his engineering degree. At the suggestion of Professor Dana Mitchell, Dunning offered Anderson a teaching assistant position if he would also help design and build the cyclotron. While working on his doctorate, Anderson made two major contributions to the project. The first was to design a high frequency filament supply, rather than the commonly used direct current version. This fostered longer filament life in the high magnetic field environment of a cyclotron. The second and more important contribution was the use of a pair of concentric lines to feed the cyclotron dees (cyclotron electrodes in the shape of a "D"), rather than the usual induction system. This refinement resulted in greater cyclotron efficiency and became a regular feature in cyclotron design. Others assisting Anderson in the construction of the cyclotron were Eugene T. Booth, G. Norris Glasoe, Hugh Glassford, and professor Dunning. In anticipation of conducting experiments with the cyclotron, Anderson also built an ionization chamber and a linear amplifier in late 1938.[3][4][5] In December 1938, the German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann sent a manuscript to Naturwissenschaften reporting they had detected the element barium after bombarding uranium with neutrons;[6] simultaneously, they communicated these results to Lise Meitner. Meitner, and her nephew Otto Robert Frisch, correctly interpreted these results as being nuclear fission.[7] Frisch confirmed this experimentally on January 13, 1939.[8] In 1944, Hahn received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission. Some historians have documented the history of the discovery of nuclear fission and believe Meitner should have been awarded the Nobel Prize with Hahn.[9][10][11] Even before it was published, Meitner's and Frisch's interpretation of the work of Hahn and Strassmann crossed the Atlantic Ocean with Niels Bohr, who was to lecture at Princeton University. Isidor Isaac Rabi and Willis Lamb, two University of Columbia physicists working at Princeton, heard the news and carried it back to Columbia. Rabi said he told Fermi; Fermi gave credit to Lamb. Bohr soon afterwards went from Princeton to Columbia to see Fermi. Not finding Fermi in his office, Bohr went to the cyclotron area and found Anderson. Bohr grabbed him by the shoulder and said: "Young man, let me explain to you about something new and exciting in physics."[12] It was clear to scientists at Columbia that they should try to detect the energy released in the nuclear fission of uranium from neutron bombardment. On January 25, 1939, Anderson was a member of the experimental team at Columbia University that conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States,[13] which was conducted in the basement of Pupin Hall; the other members of the team were Eugene T. Booth, John R. Dunning, Enrico Fermi, G. Norris Glasoe, and Francis G. Slack.[14] Fermi had arrived at Columbia a short time before this historic demonstration. This bringing together of Fermi and Anderson resulted in a rewarding relationship lasting until the death of Fermi in 1954. Fermi and Anderson conducted a series of experiments at Columbia on the slowing of neutrons in graphite, absorption and reflection of slow neutrons by numerous relevant materials, fissioning of uranium, and preliminary experiments using a lattice of uranium in graphite. A paper based on Anderson's PhD thesis, Resonance Capture of Neutrons by Uranium,[15] for security reasons, was not published until 10 years later.[3] Chain reactionIn February 1942, as part of the Manhattan Project, the Metallurgical Laboratory (Met Lab) was established at the University of Chicago. Anderson worked under Fermi in the design and construction of Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), which achieved the first manmade nuclear chain reaction on December 2, 1942.[16][17][18] Thereafter, Anderson led the construction of CP-2 at Argonne National Laboratory in 1943. He was also a key consultant to DuPont in the design and construction of the Hanford reactors, which generated fissionable plutonium for the U.S. nuclear arsenal.[3] In 1944, Anderson went to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, where he participated in using the Omega reactor to determine the critical mass of uranium-235. In preparation for the first nuclear device test on July 16, 1945, which was codenamed Trinity, Anderson, with his radiochemist colleagues, developed a method of determining the nuclear yield by collecting fission products at the detonation site. This technique was later perfected for nuclear yield determinations through the analysis of airborne fission products.[3][19] After the conclusion of World War II, Fermi and Anderson returned to the University of Chicago. There, they established the Institute for Nuclear Studies (today the Enrico Fermi Institute). At the University, Anderson was assistant professor of physics 1946 to 1947, associate professor 1947 to 1950, professor 1950 to 1977, and distinguished service professor 1977 to 1982. From 1958 to 1962, Anderson was director of the Enrico Fermi Institute.[3] In addition to Anderson's work in Italy and Brazil, he was intermittently at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Finally, he returned there in 1978 as a fellow and then a senior fellow until his death from an almost 40-year struggle with berylliosis. His death on July 16, 1988, at Los Alamos, New Mexico, was on the 43rd anniversary of the first test of an atomic bomb.[3] DeathAnderson's death was caused by lung failure, a derivative result of berylliosis — chronic beryllium poisoning, which he contracted during his work on the uranium project during the early days of World War II. Honors and appointmentsAnderson's distinguished career earned him a number of honors:[3]

Works

ReferencesCitations

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||