|

Helen Barrett MontgomeryHelen Barrett Montgomery (July 31, 1861 – October 19, 1934) was an American social reformer, educator and writer. In 1921, she was elected as the first woman president of the Northern Baptist Convention (and of any religious denomination in the United States). She had long been a delegate to the Convention and a policymaker. In 1893, she helped found a chapter of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union in Rochester, New York, and served as president until 1911, nearly two decades. In 1899, Montgomery was the first woman elected to the Rochester School Board and any public office in the city, 20 years before women could vote. Montgomery was an activist for women's and overseas missions and a successful fundraiser; in 1910-1911, she raised one million dollars by her national speaking tour (the funds raised were equivalent to $23.7 million in 2010), used chiefly to support colleges for women in China. In 1921 as president of the Women's American Baptist Foreign Missionary Society, she gave their "Jubilee" contributions of more than $450,000 to the National Baptist Convention. In 1924, she was the first woman to publish a translation of the New Testament from the original Greek. Living mostly in Rochester, New York, she was influential in national and international progressive movements. Since 1995, Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School has held an annual conference on Women in Church and Society, named in honor of Helen Barrett Montgomery. In addition, the School is establishing an endowed fund in her name for its Program for the Study of Women and Gender in Church and Society. Early life and educationHelen was the eldest of three children born to Amos Judson Barrett and Emily Barrows Barrett, both of whom were then teachers. She was born in Kingsville, Ohio. Her parents moved to Rochester, New York when she was a child so that her father could attend the Rochester Theological Seminary.[1] After he graduated in 1876, he was called as pastor of Lake Avenue Baptist Church in the city. He served there until his death in 1889, when Helen was 28. Helen Barrett studied at Wellesley College, where she graduated with teacher certification in 1884. She had studied and excelled in Greek, leading her class. (Later she would write and publish a translation of the New Testament.) She taught in Rochester and then at the Wellesley Preparatory School in Philadelphia.[2] Marriage and familyOn September 6, 1887, Barrett married a Rochester businessman, William A. Montgomery, owner of North East Electric Company. (This eventually became the Rochester Products Division of General Motors.) They adopted a daughter, whom they named Edith Montgomery.[1] Public careerHelen Barrett Montgomery's life work may be described under four headings: church, social reforms to benefit women, Bible translation, and missions. She has been described by the scholar Kendal Mobley as a "domestic feminist":

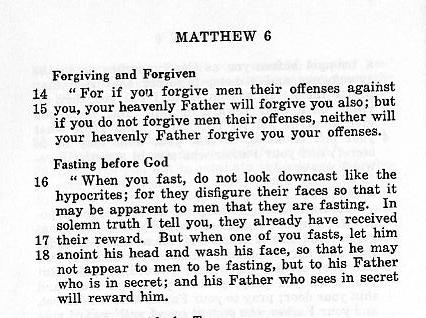

Church and Northern Baptist ConventionBarrett Montgomery stayed on at Lake Avenue Baptist Church. (Her father died two years after her marriage.) In 1892, the congregation licensed her to preach (not the same as ordination as a minister). She organized and taught a women's Bible class at the church, which she led for 44 years in the midst of her other activities.[2] Her involvement and leadership in church circles and the city's women's movement led Montgomery to serve as a delegate to annual meetings of the Northern Baptist Convention, the association of Northern Baptist churches, where she helped decide policy. The Convention was formed in 1907, bringing together most Baptists in the North who were associated with the historical missions to establish schools and colleges for freedmen in the South after the American Civil War. Now the American Baptist Churches USA, the association of Northern Baptist churches was also active in missions to Asia, particularly China.  In 1921, Montgomery was the first woman to be elected president of the Northern Baptist Convention (NBC), and of any religious denomination in the United States.[4] As president of the Women's American Baptist Foreign Mission Society, she had given their gift of more than US$450,000 to the NBC. She was elected after having demonstrated her successful fundraising. During her year as president of the NBC, Montgomery spent considerable time in trying to prepare the churches for a new "statement of faith." She worked to prevent the Convention from being taken over by fundamentalists and requiring an official confession. Her correspondence during this period showed that she was motivated by her "defense of the cherished Baptist principle of liberty."[5] Speaking to the third Baptist World Congress in 1923, Montgomery said, "Jesus Christ is the great Emancipator of woman. He alone among the founders of the great religions of the world looked upon men and women with level eyes, seeing not their differences, but their oneness, their humanity."[6] She strongly believed that women had an active role to play in the church and society. Social reforms to benefit womenMontgomery worked on social reforms in the United States, especially those to benefit women. In 1893, she joined with Susan B. Anthony, the activist for civil rights who was nearly 40 years older, in forming a new chapter of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union (WEIU) in Rochester. Montgomery served as president from 1893-1911, which "enabled her to exert broad influence in the city's social and political affairs."[3] She and Anthony worked together for more than a decade on women's issues in Rochester. Following the example of chapters in Buffalo and Boston, the WEIU of Rochester served poor women and children in the city, which was attracting many Southern and Eastern European rural immigrants for its industrial jobs. The WEIU also founded a legal aid office, set up public playgrounds, established a "Noon Rest" house where working girls could eat unmolested, and opened stations for mothers to obtain safe milk, which later developed as public health clinics. It developed as one of the most important Progressive institutions in the city.[3] Montgomery also became known in the city for her advocacy of education. Aided by the support of many women's groups,[3] in 1899, she was the first woman elected to the Rochester School Board, as well as to any public office in Rochester,[2] 20 years before women had the right to vote. She was elected during a time when women had few public roles and rarely spoke in such venues. She was re-elected and served a total of 10 years as a member of the Board. During her tenure, Montgomery implemented several reforms to the public school system, such as introducing kindergarten and vocational training in public schools, and including health education in the curriculum. In 1898, Montgomery and Susan B. Anthony responded to a challenge by the trustees of the University of Rochester, who had voted to make it coeducational if women's groups raised $100,000 to help with expenses. They led 25 women's clubs in the city to raise money for a fund to support the admission of women students, reaching agreement with the trustees after collecting $50,000 by 1900. (The university was coed until 1909, then established a separate facility for women, which lasted until 1955.)[3] As Montgomery's interest in education for women was not limited to the US, she also raised funds for missionaries in Asia to start Christian colleges for women, particularly in China. Her national speaking tour in 1910-1911 raised $1 million for this purpose. (See below under "Christian missions".)[2] Bible translationMontgomery was the first woman to translate the New Testament into English from Greek and have it published by a professional publishing house.[7] (Julia E. Smith published her translation privately, paying for it herself.) Montgomery was inspired to write a new English translation because of her experience teaching street boys in her church, and finding they did not understand the dated language of the King James Version of the Bible. When she used the Weymouth New Testament (1903), they understood it much better but she was still not satisfied. She decided to write her own translation to "make it plain" for the "ordinary" reader. It was published in 1924 as The Centenary Translation, issued by the American Baptist Publication Society in celebration of its 100th anniversary. This version has been reprinted as The New Testament in Modern English, with a spine and cover labeled Montgomery New Testament. Hers is the only English translation by a Baptist woman that has been published.[5] Montgomery's translation was notable for her practice of inserting chapter and section titles (as seen in photo), a pioneering feature now commonly used in Bibles in many languages. She included interpretations supporting enlarged roles for women in the church, which was influenced by her reading the works of Katharine Bushnell, a Methodist missionary.[7] (Bushnell's work was rediscovered by theologians in 1975.) Montgomery had reviewed an edition of Bushnell's collection God's Word for Women in 1924, but likely first came across the work when it was published in 1919.[7] Bushnell's influence is seen in Montgomery's translating 1 Cor.11:13-15 as statements rather than questions (as formerly interpreted by others), as illustrated below with comparisons between the New American Standard Bible and the King James Version. In addition, her notes to Rom 16:2 and to I Cor. 14:34 show her "familiarity" with Bushnell's argument.[8] Montgomery: "It is fitting that a woman should pray to God with her head unveiled." NASB: "Is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered?" KJV: "Is it comely that a woman pray unto God uncovered?" Christian missionsMontgomery supported missions by a variety of activities: her national speaking tour (1910–1911) raised $1 million for the mission fund (worth $23.7 million in 2010).[9] Much of the money was used to establish colleges for women in China.[2] She wrote books to publicize the missions. Her book, Western Women in Eastern Lands (1910), studied the role of women missionaries and women's mission boards overseas. This was a time of extensive Christian missionary activity in East Asia, especially China. In 1913, at the request of the National Federation of Women's Boards of Foreign Missions, Montgomery traveled extensively in East Asia to study conditions of the ecumenical missions and women. Her work, The King's Highway (1915), sold 160,000 copies.[2] She also served as president of the Women's American Baptist Foreign Mission Society (1914–1924). In this capacity, in 1921 she provided a "Jubilee" gift to the Northern Baptist Convention of more than $450,000, which the women's Foreign Mission Society had raised.[5] Montgomery served as president of the National Federation (1917–1918). She also helped found the World Wide Guild, an organization that encouraged young women to become involved in missions. Not limiting her audience to adults, Montgomery worked as associate editor of Everyland, a magazine for children that reported on international missions. Legacy and honors

Works

The following is a partial list of writings by Helen Barrett Montgomery:

References

Further reading

External links |