|

Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard (French pronunciation: [ɛktɔʁ ɡimaʁ], 10 March 1867 – 20 May 1942) was a French architect and designer, and a prominent figure of the Art Nouveau style. He achieved early fame with his design for the Castel Beranger, the first Art Nouveau apartment building in Paris, which was selected in an 1899 competition as one of the best new building facades in the city. He is best known for the glass and iron edicules or canopies, with ornamental Art Nouveau curves, which he designed to cover the entrances of the first stations of the Paris Metro.[1] Between 1890 and 1930, Guimard designed and built some fifty buildings, in addition to one hundred and forty-one subway entrances for Paris Metro, as well as numerous pieces of furniture and other decorative works.[2] However, in the 1910s Art Nouveau went out of fashion and by the 1960s most of his works had been demolished, and only two of his original Metro edicules were still in place.[3] Guimard's critical reputation revived in the 1960s, in part due to subsequent acquisitions of his work by Museum of Modern Art, and art historians have noted the originality and importance of his architectural and decorative works.[2] Guimard was a disciple of Viollet le Duc.[4] Early life and educationHector Guimard was born in Lyon on 10 March 1867. His father, Germain-René Guimard, was an orthopedist, and his mother, Marie-Françoise Bailly, was a linen maid. His parents married on 22 June 1867. His father became a gymnastics teacher at the Lycée Michelet in Vanves in 1878, and the following year Hector began to study at the Lycée. In October 1882 he enrolled at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs, or school of decorative arts. He received his diploma on 17 March 1887, and promptly enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied architecture. He received honorable mention in several architectural competitions, and also showed his paintings at the Paris Salon des Artistes in 1890, and in 1892 competed, without success, in the competition for the Prix de Rome. In October 1891 he began to teach drawing and perspective to young women at the École nationale des arts decoratifs and later a course on perspective for younger students, a post he held until July 1900.[5] He showed his work at the Paris Salons of April 1894 and 1895, which earned him a prize of a funded voyage first to England and Scotland, and then, in the summer of 1895, to the Netherlands and Belgium. In Brussels in the summer of 1895, he met the Belgian architect Victor Horta, one of the founders of Art Nouveau, and saw the sinuous vegetal and floral lines of the Hotel Tassel, one of the earliest Art Nouveau houses. Guimard arranged for Horta to have an exhibition of his designs at the January 1896 Paris Salon, and Guimard's own style and career began to change.[6] Early career (1888–1898)Early worksThe earliest constructed work of Guimard was the cafe-restaurant Au Grand Neptune (1888),[7] located on the Quai Auteuil in Paris at the edge of the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889. It was picturesque but not strikingly innovative. It was demolished in 1910. He constructed another picturesque structure for the Exposition, the Pavilion of Electricity, a showcase for the work of electrical engineer Ferdinand de Boyéres. Between 1889 and 1895 he constructed a dozen apartment buildings, villas and houses, mostly in the Paris 16th arrondissement or suburbs, including the Hotel Roszé (1891) and the Hotel Jassedé (1893) without attracting much attention. He earned his living primarily from his teaching at the School of Decorative Arts.[8] The Castel Béranger (1895–1898)Guimard's first recognized major work was the Castel Béranger in Paris, an apartment building with thirty-six units constructed between 1895 and 1898, when the architect was just thirty years old. It was at 14, rue Jean de la Fontaine, Paris, for Mme. Fournier. He persuaded his client to abandon a more restrained design and replace it with a new design in a more modern style, similar to that of Horta's Hotel Tassel, which he had visited in the summer of 1895.[6] Guimard put together an extraordinary number of stylistic effects and theatrical elements on the facade and in the interior, using cast iron, glass and ceramics for decoration. The lobby, decorated with sinuous vine-like cast iron and colorful ceramics, resembled an undersea grotto. He designed every detail, including the wallpaper, rain spouts and door handles, and added adding highly modern new features including a telephone booth in the lobby.[9] A skilled publicist, Guimard very effectively used the new building to advertise his work. He had his own apartment and office in the building. He organized conferences and press articles, set up an exhibition of his drawings in the salons of Le Figaro, and wrote a monograph on the building. In 1899 he entered it into the first Paris competition for the best new building facades, and in March 1899 it was selected one of the six winners, a fact which he proudly had inscribed on the facade of the building.[9]

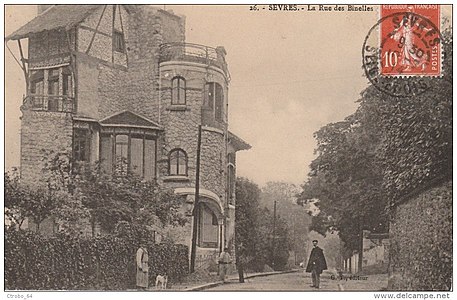

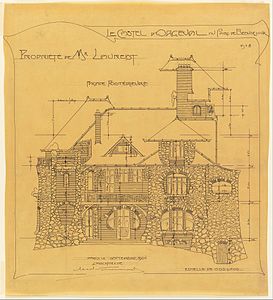

Mature career (1898–1914)Castels, villas and a short-lived concert hallThe success and publicity created by the Castel Beranger quickly brought him commissions for other residential buildings. Between 1898 and 1900, he constructed three houses simultaneously, each very different but recognizably in Guimard's style. The first, the Maison Coilliot, was built for the ceramics manufacturer Louis Coilliot on rue de Fleurs in Lille, and served as his store, reception hall and residence. The facade was covered with plaques of green enamelled volcanic rock, and decorated with soaring arches, curling wrought iron, and Guimard's characteristic asymmetric, organic doorways and windows.[10] The following year, 1899, while he continued to teach regularly at the school of decorative arts in Paris, and continued construction of the Maison Coilliot, he began three new houses; The Modern Castel or Villa Canivet in Garches was Guimard's reinvention of a medieval castle. La Bluette in Hermanville-sur-Mer was Guimard's update of traditional Norman architecture. and the Castel Henriette, in Sevres. The Castel Henriette was the most inventive. It was located on a small site, almost circular, and was crowned with a tall, slender watchtower. To create more open interior space, Guimard moved the stairwell to the side of the building. The interior was lit by large windows, and featured ensembles of furniture all designed by Guimard. The building had an unhappy history. The watchtower fell in 1903, apparently after being struck by lightning. Guimard was summoned back and redesigned the house, adding new balconies and terrace. However, by the 1960s, the building was considered out of fashion, and it was rarely occupied. It served as a movie set before it was finally demolished, despite appeals by preservationists. Some of the furniture is now found in museums.[10] In 1898, Guimard embarked upon another ambitious project, the construction of a concert hall, the Salle Humbert-de-Romans, located at 60 Rue Saint Didier (16th arrondissement). It was built as the centrepiece of a conservatory of Christian music intended for orphans, proposed by a priest of the Dominican order, Father Levy. Guimard made an ambitious and non-traditional plan using soaring levels of iron and glass, inspired by an early idea of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. An organ manufacturer, in consultation with Camille Saint-Saëns, donated a grand organ. The Salle was completed in 1901, but a scandal involving Father Levy and the orphans broke out. Father Levy was exiled by the Pope to Constantinople, the foundation was dissolved, and the concert hall was used only for meetings and conferences. It closed in 1904 and was demolished in 1905. The grand organ moved to the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul in Clichy, where it can be found today.[11][12]

Paris Metro entrancesThe highly publicized debut of the Hotel Béranger quickly brought Guimard new projects, including villas, a Paris concert hall, and, most famously, entrances for the stations of the new Paris Metro, which was planned to open in 1900 in time for the Paris Universal Exposition. A new organization, the chemin de fer métropolitan de Paris (CFP, now RATP) was created in April 1899 to build and manage the system. They organized a competition for station entrance edicules, or canopies, and balustrades, or railings. This attracted twenty-one applicants. Guimard did not apply. The twenty-one original applicants proposed edicules built of masonry, in various historic and picturesque styles. These were ridiculed in the press as resembling newspaper stands, funeral monuments, or public toilets. Time was short, and Guimard presented sketches of his own idea for entrances made of iron and glass, which would be quicker and simpler to manufacture. He was given the commission on 12 January 1900, just a few months before the opening of the system.[13] To simplify the manufacture, Guimard made two designs of edicules, called Type A and B. Both were made of cast iron frames, with cream-colored walls and glass roofs to protect against rain. The A type was simpler and more cubic, while the B was rounded and more dynamic in form, and is sometimes compared with a dragonfly. Only two of the original A types were made and neither still exists. Only one B type, restored, remains in its original location, at Porte Dauphine.[14] Guimard also designed a simpler version, without a roof, with railings or balustrades of ornamental green-painted iron escutcheons and two high pylons with lamps and a 'Métropolitain' sign. The pylons were in an abstract vegetal form he invented, not resembling any particular plant, and the lettering was in a unique which Guimard invented. These were the most common type.[14] From the beginning, Guimard's Metro entrances were controversial. In 1904, after complaints that the new Guimard balustrade at the Opera station was not in harmony with the architecture of the Palais Garnier opera house, the Metro authorities dismantled the entrance and replaced it with a more classical model. Garnier was sarcastic in his response in the Paris La Press of Paris on 4 October 1904. "Should we harmonise the station of Père-Lachaise with the cemetery by constructing an entrance in the form of a tomb? ... Should we have a dancer with her leg raised in front of the station at place Dame-Blanche, to harmonise with the Moulin-Rouge?"[14] From the beginning, Guimard was also in conflict with the Metro authorities about his payments. The dispute was ended in 1903 with an agreement by which Guimard received payment, but gave up his models and manufacturing rights. Construction of new stations continued using his design without his participation. Between 1900 and 1913,[15] a total of 167 entrances were installed, of which sixty-six still survive, mostly in locations different from their original placement.[14]

Late villasIn the early years of the 20th century, Guimard's popularity diminished and his earlier frenetic pace of production slowed down. His works shown at the 1903 Paris Exposition of residential architecture did not attract the attention of the Castel Beranger and other earlier work. He was supported largely by one wealthy client, Léon Nozal, and his friends. His works for this group included the La Sapiniere, a small beach house at Hermanville-sur-Mer, near his earlier La Bluette house; La Surprise, a villa at Cabourg; and the Castel Val at Auvers-sur-Oise. In Paris he constructed the Hotel Nozal on Rue Ranelagh for his friend; the Hotel Jassadé for Louis Jassadé on Avenue de Versailles; and the palatial Castel d'Orgeval, which was the centrepiece of a new residential development at Villemoisson-sur-Orge in the Paris suburbs.[16]

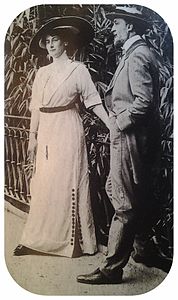

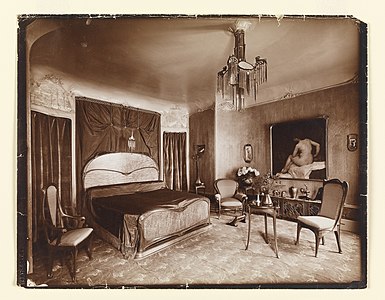

The Hôtel GuimardThe most important work of this period is the Hotel Guimard, built in 1909 at 122 Avenue Mozart (XVIth arrondissement) in Paris, ten years after his first success with the Hotel Beranger. It was built following his marriage with Adeline Oppenheim, an American painter from a wealthy family. The land was purchased three months after the marriage, and in June 1910 Guimard was able to move the offices of his agency into the ground floor. The house was not occupied by the couple, however, for two more years, while the furniture he designed was manufactured. The house is located on a triangular lot, which proved particularly challenging for Guimard. He saved interior space by installing an inclined elevator rather than a stairway on the upper floors. The house was designed to show its functions on the facade; his wife could paint in one portion of the house, with large windows, while he worked in his bureau in another part of the house. It had a very large dining room and many tables, but no kitchen; it was apparently designed for working and entertaining. The house was later broken up into apartments, and the original room arrangements and furniture are gone.[17]

Apartments, the Hôtel Mezzara and a synagogueBy the 1910s, Guimard was no longer the leader of Paris architectural fashion, but he continued to design and build residences, apartment buildings, and monuments. Between 1910 and 1911 he built Hôtel Mezzara for Paul Mezzara, experimenting with skylights. Another notable work of this period is the Agoudas Hakehilos Synagogue at 10 Rue Pavé (IV arrondissement) in the Marais district. The synagogue, Guimard's only religious building, is characterised by a narrow façade clad in white stone, whose surface curves and undulates while highlighting verticality. Like with his previous projects, Guimard designed the interiors as well, organising the spaces and creating original furnishings that matched the architectural motifs of the structure. The construction begun in 1913 with the inauguration taking place on 7 June 1914, just a few weeks before the beginning of the First World War.

Late career (1914–1942)World War I and post-war yearsBy the time the First World War began in August 1914, Art Nouveau was already out of fashion. The army and war economy took almost all available workers and building materials. Most of Guimard's projects were shelved. and Guimard gave up his furniture workshop on Avenue Perrichont. He left Paris and to reside most of the war in a luxury hotel in Pau and Candes-Saint-Martin, where he wrote essays and pamphlets calling for an end to militarized society, and also, more practically, studying ideas standardized housing that could be constructed more quickly and less expensively, anticipating the need to reconstruct housing destroyed in the War. He received a dozen patents for his new inventions.[18][19] One of the rare completed buildings still standing from this period is the office building at 10 Rue de Bretagne, begun in 1914 but not completed until after the War in 1919.[20][21] The Art Nouveau style was replaced by a more functional simplicity, where the reinforced concrete structure defined the exterior of the building. The postwar shortages of iron and other materials affected the style; there was little decoration of the facade, or entrance. He concentrated his attention on the parapets which gave the building a soaring, modern profile.[22][23] Just before the First World War he had created a firm, the Sociéte général de constructions modernes, with the intention of building standardized housing at a modest price. He returned to Paris and in 1921–22, and built a small house at 3 Square Jasmin (16th arrondissement) designed to be a model for a series of standard houses, but it was not duplicated. He was unable to keep up with the rapid changes in styles and methods, and his firm was finally dissolved in July 1925.[24]

In 1925, he participated in the Paris Exposition of Decorative and Modern Arts, the Exposition which gave its name to Art Deco, with a proposed model of a town hall for a French village. He also designed and built a parking garage and several war memorials and funeral monuments. He continued to receive honors, particularly for his teaching at the École national des arts decoratifs. In February 1929 he was named a Chevalier in the French Legion d'honneur.[24] After the war, Art Deco emerged as the leading style of Parisian architecture. Guimard adapted to the new style and proved his originality and attention to the detail. His buildings display geometric decorative patterns, simplified columns emphasizing structural elements and rigid shapes; despite this they retain elements of his previous style: sinuous lines, vegetal-inspired ornaments and typical Art Nouveau iron railings.[19] The Guimard Building and final worksHis next project, the Guimard Building, an apartment building at 18 Rue Henri Heine, Paris (XVI arrondissement, begun in 1926. is his last major project still standing. He made a skilful of different-colored brick and stone to create decorative designs on the facade, and added triangular sculpted windows on the roof level, and, in the interior. a very remarkable central stairway with curling iron railings and hexagonal windows of colored and clear glass bricks In 1928 he entered the building into the competition for the best Paris facades, the same competition that he had entered in 1898 with the Hôtel Beranger. He was a winner again, and was the first Paris architect to enter twice and to win twice. This building became his residence, though he was not able to move in until 1930.[25] Despite his success with the facade competition, his late work appeared old fashioned, particularly compared with the modernism of the Paris buildings of Robert Mallet-Stevens, Auguste Perret, and Le Corbusier. Between 1926 and 1930 he built several residential buildings in the same neighborhood as his home in the 16th arrondissement, which still exist. These include the Hôtel Houyvet, at 2 Villa Flore and 120 Avenue Mozart, built for the industrialist Michel Antoine Paul Houyhvet. His last recorded work was La Guimardière, an apartment building on Avenue Le Nôtre, Vaucresson in the Hauts-de-Seine suburb of Paris. It was completed in about 1930, but was demolished in March–April 1969.[24]

As early as 1918, he took steps to assure that his work would be documented and would survive. He obtained space in the former orangerie of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where he deposited models of his buildings and hundreds of designs. In 1936 he donated a large collection of his designs to Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1937, he received authorisation to put thirty cases of models in the cellars of the National Museum of Antiquities in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye.[24] Guimard served as a member of the jury judging architectural works at the 1937 Paris Exposition, where he could hardly miss the monumental pavilion of Nazi Germany and the threat it presented. His wife was Jewish, and he was alarmed by the approaching likelihood of war. In September 1938 he and his wife settled in New York City. He died on 20 May 1942 at the Hotel Adams on Fifth Avenue. He is buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York, about 25 miles north of New York City.[24] Obscurity and rediscoveryAfter the War, in June–July 1948, his widow returned to Paris to settle his affairs. She offered the Hotel Guimard as a site for a Guimard Museum first to the French state, then to the City of Paris, but both refused. Instead, she donated three rooms of Guimard's furniture to three museums; the Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, and the Museum of the Petit Palais, where they are now displayed. She also donated a collection of three hundred designs and photographs to the Museum of Decorative Arts. These disappeared into various archives in the 1960s, but were relocated in 2015. His widow died on 26 October 1965 in New York.[26] [24] By the time of Guimard's death, many of his buildings had already been demolished or remodeled beyond recognition. Most of his original Metro station edicules and balustrades had also been removed. The only full covering remaining at its original location at Porte Dauphine. However, many original architectural drawings by Guimard were stored in the Dept. of Drawings & Archives at Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University in New York City, and in the archives of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. [24] The re-evaluation and rehabilitation of Guimard's reputation began in the late 1960s. Portions of the Castel Beranger were declared of historic and artistic value in July 1965, and the entire building was protected in 1989.[27] His reputation was given a major boost in 1970, when the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted a large exhibition of his work, including drawings he had donated himself and one of his Metro Station edicules. Other museums followed. The thirty cases of models in the cellars of the National Museum of Antiquities in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye were rediscovered and some were put on display. In 1978, all of Guimard's surviving Metro entrances (Eighty-eight of the original one hundred sixty-seven put in place) were declared of historic value. The city donated a few originals, and several copies, to Chicago and other cities which desired them. Reconstructed original edicules are found at Abbesses and Châtelet.[28] Many of his buildings have been substantially modified, and there are no intact Guimard interiors which are open to the public, though suites of his furniture can be found in the Museum of Decorative Arts and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. He is honoured in street names in the French towns of Châteauroux, Perpignan, Guilherand-Granges and Cournon-d'Auvergne, and by the rue Hector Guimard in Belleville, Paris. FurnitureLike other prominent Art Nouveau architects, Guimard also designed furniture and other interior decoration to harmonize with his buildings. It took him some time to find his own style in furniture. The furniture he designed for the Hotel Delfau (1894), which he put on display at an Exposition in 1895, was picturesque and ornate, with a sort of star motif, which seemed to have little connection with the architecture of the house. His early furniture sometimes featured had long looping arms and lateral shelves and levels for displays of objects. He apparently did not produce any furniture for the Hotel Beranger, other than a desk and chairs for his own studio there. In his early years he is known to have produced only two full sets of furniture, a dining room set for the Castel Henriette and a dining room for the Villa La Bluette.He also designed furnishings without any particular room in mind, as he did with watercolor designs for the Russian Princess Maria Tenisheva in 1903.[29] His furniture style began to change in about 1903. He found a workshop to make his furniture, and began using finer woods, particularly pear wood, with delicate colors. He simplified he plans, and eliminated the excessive number of arms and shelves. The most notable examples of his late style are pieces made for the Hôtel Nozal (since destroyed) and now in the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris. Other examples of the late style are from the Hotel Guimard, now in the Petit Palais and the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, and Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.[29]

The Guimard Style

Much of the success of Guimard came from the small details of his designs, from door handles and balcony railings to type faces, which he crafted with special imagination and care. He invented his own style of lettering which appeared on his Metro entrances and his building plans. He insisted on calling his work "Style Guimard", not Art Nouveau, and he was genius at publicizing it. He wrote numerous articles and gave interviews and lectures on his work, and printed a set of "Style Guimard" postcards with his pictures of his buildings, [30] Guimard rejected the dominant academic Beaux-Arts style of there 1880s, calling it "cold receptacle of various past styles in which the original spirit was no longer alive enough to dwell".[2] His fellow students at the National School of Decorative Arts nicknamed him the "Ravachol of architecture", after Ravachol, the Paris anarchist who bombed church buildings.[2] Nonetheless, he was recognized for his designing skills; in 1884 he was awarded three bronze and two silver medals at the school for his work. In 1885 he received awards in all of the competitions at the school, including four bronze medallions, five silver, and the school's Grande Prix d'Architecture. Guimard's early Art Nouveau work, particularly the Castel Beranger, as Guimard himself acknowledged, was strongly influenced by the work of the Belgian architect Victor Horta, especially the Hotel Tassel, which Guimard visited before he designed the Castel Beranger. Like Horta, he created original designs and ornament, inspired by his own views of nature. If the skylights favored by Victor Horta are rare in his work (the Mezzara Hotel, 1910, and the Rue Pavée Synagogue, (1913), being notable exceptions), Guimard made noteworthy experiments in space and volume. These include the Coilliot House[31] and its disconcerting double-frontage (1898), and the Villa La Bluette,[32] noted for its volumetric harmony (1898), and especially the Castel Henriette[33] (1899) and the Castel d'Orgeval[34] (1905), demonstrations of an asymmetrical "free plan", twenty-five years before the theories of Le Corbusier. Other buildings of his, like the Hôtel Nozal (1905), employ a rational, symmetrical, square-based style inspired by Viollet-le-Duc.[35] Guimard employed some structural innovations, as in the concert hall Humbert-de-Romans[36] (1901), where he created a complex frame to divide sound waves to produce enhanced acoustics (built 1898 and demolished in 1905), or as in the Hôtel Guimard (1909), where the ground was too narrow to have the exterior walls bear any weight, and thus the arrangement of interior spaces differs from one floor to another.[37] In addition to his architecture, furniture, and wrought iron work, Guimard also designed art objects, such as vases, some of which were produced by the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres outside Paris. A notable example is the Vase of Binelles (1902), made by crystallization on hard porcelain, which is now in the National Museum of Ceramics in Sèvres. Guimard was a determined advocate of architectural standardization, from mass-producing Metro station edicules and balustrades to (less successfully) the mass production of cast iron pieces and other prefabricated building materials intended for the assembly rows of houses. entrances to the Paris Métro,[38] based on the ornamented structures of Viollet-le-Duc.[39] The idea was taken up – but with less success – in 1907 with a catalogue of cast iron elements applicable to buildings: Artistic Cast Iron, Guimard Style.[40] Guimard's art objects have the same formal continuity as his buildings, harmoniously uniting practical function with linear design, as in the Vase des Binelles,[41] of 1903. His stylistic vocabulary has suggestions to plants and organic matter and has been described as a form of "abstract naturalism".[2] Undulating and coagulating forms are found in every material from stone, wood, cast iron, glass (Mezzara hotel, 1910), fabric (Guimard hotel, 1909), paper (Castel Béranger, 1898), wrought iron (Castel Henriette, 1899), and ceramic (Coilliot House, 1898); Guimard compared it analogously to the flowing of sap running from a tree, referring to the liquid quality found in his work as the "sap of things".[2] Guimard's structural forms remain only as abstract evocations of nature and never directly indicative of any particular plant, an approached outlined by the art critic and contemporary, Gustave Soulier who said about Guimard's work:

Chronology of notable buildings        1889

1891

1892

1893

1894

1895

1896

1898

1899

1900

1901

1903

1904

1905

1906

1907

1909

1910

1911

1913

1914

1919

1920

1922

1923

1926

1927

1928

1930

See also

Notes

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Hector Guimard.

|

||||||||||||||||