|

H.J. de Graaf

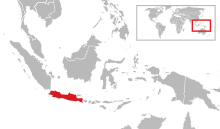

Hermanus Johannes de Graaf (2 December 1899 – 24 August 1984) was a Dutch historian specialising in the history of Java, Indonesia, the world's most populous island. Trained as historian at Leiden University, he moved to Batavia (today's Jakarta) to take a government job, and later became a teacher for various schools in Indonesia. At the same time, he pursued his interest in the history of Indonesia and published books and articles on the topic. After a brief assignment at the University of Indonesia, he returned to the Netherlands. He taught at various institutions, including Leiden, until 1967 and continued to publish scholarly works, even after his retirement. He suffered a serious stroke in 1982 and died two years later. His works covered the history of Indonesia in general, with emphasis on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Java. His works extensively consulted both European and Indonesian sources, one of the first trained historians to do so. Historian M. C. Ricklefs called him the "father of the study of Javanese history", while Javanist Theodoor Gautier Thomas Pigeaud said his works formed "a substantial contribution to the study of the national history of Indonesia." BiographyEarly life De Graaf was born on 2 December 1899 in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, where he attended school. In 1919, he went to Leiden University to study history. The historian and orientalist Johan Huizinga was among his professors there. In 1926 he took up a government job in Dutch East Indies (today's Indonesia). While he sailed to Batavia (today's Jakarta), he read about Indonesian history, sparking his interest for the first time. He was posted at Surabaya to become a history teacher in a Hogere Burgerschool (HBS, high school) for a year. Subsequently, he moved to Batavia, first to work at the city's museum library, and then at the Inspectorate of Middle Schools. While at Batavia he met the Javanese professor Poerbatjaraka, who then gave him weekly lessons in Javanese language and culture. He began to pursue his scholarly interest while still having the Inspectorate job. His first scholarly article was published in 1929. In the same year he married a teacher, Carolinia Johanna Mekkink.[1] Academic career in IndonesiaIn 1931 de Graaf left government service and became a schoolmaster in Malang, and then Prabalingga. In 1935 he returned to Leiden to earn his doctorate. His supervisor was H. T. Colenbrander, whose work had initially sparked his interest in Indonesian history. His dissertation was on the murder of Captain François Tack in the Mataram court in 1686,[2] In 1935, he returned to the Indies and resumed teaching in Surakarta. He took his Javanese students to visit historical sites and Islamic holy sites throughout Java, despite the school being a Protestant school. During school vacations he continued his research in Batavia, publishing articles on the Trunajaya rebellion and the fall of Mataram. He also wrote for the Chinese Geschiedenis in 1941. Fear about the work's unflattering description of the Japanese led its publisher to largely destroy it in 1942 as the Japanese took over the Indies as part of World War II.[3] He was then interned and spent the war in several camps and befriended the linguist C. C. Berg. De Graaf's wife was interned separately in a women's camp, and in 1944 their nine-year-old daughter Elisabeth Anna died in captivity.[4] World War II was followed by the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–49) which pitted the newly independent Indonesia against the Dutch trying to regain its colony. He taught briefly in Bandung before Berg invited him to Jakarta to teach in what would become the University of Indonesia.[4] He accepted the invitation and stayed in Jakarta until 1950. During this period he authored various works, including The Crown of Majapahit (Dutch: Over de kroon van Madja-Pait, 1948) and his famous A History of Indonesia (Dutch: Geschiedenis van Indonesië, 1949). He also made a research trip to the Netherlands in 1947–48, during which he worked through Dutch East India Company archives sent to him in Arnhem from The Hague. He also felt disillusionment with the direction of the young Republic of Indonesia and the leadership of Sukarno.[5] This disillusionment, as well as his wife's safety concerns about teaching as a foreigner in Indonesia, and frustration over not being made a professor—he thought this was promised to him—led him to leave Indonesia for good in 1950.[6] Career in the NetherlandsDe Graaf left for the Netherlands in 1950, and in 1953 he became a privaat docent at Leiden, teaching Indonesian history. His inaugural lecture there about the Babad Tanah Jawi triggered an academic dispute with C. C. Berg. In 1955, Berg said that de Graaf relied too naively on Javanese sources material, which led him to accept the historicity of Sutawijaya—founder of Mataram and Sultan Agung's grandfather, also known as Panembahan Senapati, while Berg believed that he was a myth created to enhance Agung's legitimacy, and that Agung was the real founder. De Graaf replied in a 1956 paper, in which he disproved—with support from European sources—Berg's thesis that Agung was Mataram's founder. However, not all issues were resolved, and the continuing debate soured de Graaf's relation with Berg on both academic and personal level.[7] He continued to teach in various Dutch schools up to his retirement in 1967.[6] These years were his most productive; he wrote four important volumes on Javanese history between 1500—1700: one on the court of Mataram as visited by Dutch envoys (published 1956), one on the reign of Sultan Agung (1958) and two volumes on the reign of Amangkurat I (1961 and 1962).[8] Retirement and deathIn 1967 de Graaf retired from teaching but continued his scholarly pursuit. He regularly contributed to the magazine Tong Tong (later known as Moesson), writing about Indonesian history in a more casual style. He also published works on the Kediri campaign of 1678 in 1971, and two volumes on the 1807–08 journey of the ship De Vlieg in Brazil (published in 1975–56). Later, he met another Dutch scholar of Java Theodoor Gautier Thomas Pigeaud and, who became his friend and collaborator. In 1974, they published a history of early Muslim principalities in Java, covering a period with less certain historical sources. In 1976, Pigeaud published an English summary of eight of de Graaf's most important works, making them available to the non-Dutch-reading audience. During the same period, he also began to work on the history the Moluccas, especially on the Ambonese, whom de Graaf thought the Dutch owed a "duty of gratitude" for helping "enrich" the Dutch and spreading their authority around Indonesia. He published a comprehensive history of Ambon and South Moluccas in 1977.[9] In May 1982 he attended the annual meeting of Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies and suffered a stroke on the way home. The stroke prevented him from working, and later from communicating, until he died on 24 August 1984.[10] Works De Graaf's doctoral dissertation, on the murder of Captain François Tack in the Mataram court in 1686, was "a landmark in the study of Javanese history",[2] according to M. C. Ricklefs. While historians had studied the history of Java before him, his work combined both Javanese and European sources and made use of the historical method.[2] His 1948 study The Crown of Majapahit corrected a misunderstanding among European historians of Java, who had previously thought that the golden crown that the Dutch acquired for Amangkurat II helped legitimize his rule. De Graaf argued that crowns and coronations did not carry the same significance in the Javanese royalty as it did for Europeans. Instead, the episode contributed to Amangkurat's hatred of the Dutch for their condescension and involvement in his rule. His 1949 History of Indonesia was the most authoritative textbook on Indonesian history up to the 1970s. Unlike previous books written by Europeans, it gave more emphasis on Indonesians (in addition to Europeans).[11] During the 1950s and 1960s, among his other works, he wrote four important volumes on Javanese history between 1500—1700. The first one, published in 1956 was about the court of Mataram in 1648—54 as visited by Dutch envoys, and remains the most important source on that topic. The second one was about the reign of Sultan Agung (published 1958) and other two were about the reign of Amangkurat I (published 1961 and 1962). These volumes consulted European works, including English, Dutch, Portuguese and Danish sources, as well as Indonesian sources: Javanese and Madurese. Ricklefs praised these works, pointing out the diverse sources being used and de Graaf's ability to locate references, "however fleeting," for this period.[8] In 1971, he edited and published Johan Jurgen Briel's journal which provided accounts of the Kediri campaign of 1678. In 1974, he and Pigeaud published The First Islamic States of Java, which combined the methods of history and philology. This work became an authority on the spread of Islam in Java during the 15th and the 16th century, despite its lack of certainty given the unreliability of sources from that period.[12] Because his works were mostly in Dutch, in 1976 Pigeaud published Islamic States in Java 1500–1700: Eight Dutch Books and Articles by Dr H.J. de Graaf, an English summary of what he considered de Graaf's eight most important works, including The First Islamic States of Java, works on the reigns of Sutawijaya, Sultan Agung, Amangkurat I and Amangkurat II, including various phases of the Trunajaya rebellion. The book also provided a bibliography and index to the original works.[13][14] RecognitionsIn 1974, de Graaf was made an Honorary Member of the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies.[13] Many later scholars of Javanese history consider themselves his heirs,[10] and historian of Indonesia M. C. Ricklefs called him the "father of the study of Javanese history".[1] According to Theodoor Gautier Thomas Pigeaud, his works "form a substantial contribution to the study of the national history of Indonesia."[15] Personal lifeHe was married in 1929 to Carolina Johanna Mekkink.[16] They had four children: Hendrik (b. 1931), Johannes (b. 1933), Elisabeth Anna (b. 1935) and Anna Elisabeth (b. 1948).[2] Elisabeth Anna died in 1944 in a Japanese World War II internment camp.[4] He was a devout Protestant and held conservative political views, which sometimes put him at odds with his Dutch academic colleagues.[1] ReferencesCitations

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||