|

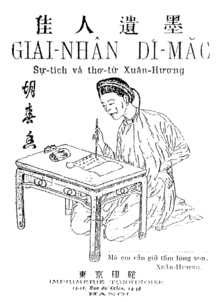

Hồ Xuân Hương

Hồ Xuân Hương (胡春香; 1772–1822) was a Vietnamese poet born at the end of the Lê dynasty. She grew up in an era of political and social turmoil – the time of the Tây Sơn rebellion and a three-decade civil war that led to Nguyễn Ánh seizing power as Emperor Gia Long and starting the Nguyễn dynasty. She wrote poetry using chữ Nôm (Southern Script), which adapts Chinese characters for writing demotic Vietnamese. She is considered to be one of Vietnam's greatest classical poets. Xuân Diệu, a prominent modern poet, dubbed her "The Queen of Nôm poetry".[1] BiographyThe facts of her life are difficult to verify, but this much is well established: she was born in Nghệ An Province near the end of the rule of the Trịnh lords, and moved to Hanoi while still a child. The best guess is that she was the youngest daughter of Hồ Phi Diễn. According to the first researchers of Hồ Xuân Hương, such as Nguyễn Hữu Tiến and Dương Quảng Hàm, she was a daughter of Hồ Phi Diễn (born in 1704) in Quỳnh Đôi Village, Quỳnh Lưu District, Nghệ An Province (*). Hồ Phi Diễn acquired the baccalaureate diploma at the age of 24, under Lê Dụ Tông's reign. Due to his family's poverty, he had to work as a tutor in Hải Hưng, Hà Bắc for his earnings. At that place, he cohabitated with a girl from Bắc Ninh, his concubine – Hồ Xuân Hương was born as a result of that love affair. Nevertheless, in a paper in Literature Magazine (No. 10, Hanoi 1964), Trần Thanh Mại claims that Hồ Xuân Hương's hometown was the same as mentioned above, but she was a daughter of Hồ Sĩ Danh (1706–1783) and a younger stepsister of Hồ Sĩ Đống (1738–1786)" She became locally famous and obtained a reputation of creating poems that were subtle and witty. She is believed to have married twice as her poems refer to two different husbands: Vĩnh Tường (a local official) and Tổng Cóc (a slightly higher level official). She was the second-rank wife of Tổng Cóc, in Western terms, a concubine, a role that she was clearly not happy with ("like the maid/but without the pay"). However, her second marriage did not last long as Tổng Cóc died just six months after the wedding. She lived the remainder of her life in a small house near the West Lake in Hanoi. She had visitors, often fellow poets, including two specifically named men: Scholar Tôn Phong Thi and a man only identified as "The Imperial Tutor of the Nguyễn Family." She was able to make a living as a teacher and evidently was able to travel since she composed poems about several places in Northern Vietnam. A single woman in a Confucian society, her works show her to be independent-minded and resistant to societal norms, especially through her socio-political commentaries and her use of frank sexual humor and expressions. Her poems are usually irreverent, full of double entendres, and erudite.[2] Legacy By composing the vast majority of her works in chữ Nôm, she helped to elevate the status of Vietnamese as a literary language. Recently, however, some of her poems have been found which were composed in Hán văn, indicating that she was not a purist. In modern times, chữ Nôm is nearly a dead script, having been supplanted by chữ Quốc ngữ, a Latin alphabet introduced during the period of French colonization. Some of her poems were collected and translated into English in John Balaban's Spring Essence (Copper Canyon Press, 2000, ISBN 1 55659 148 9). An important Vietnamese poet and her contemporary is Nguyễn Du, who similarly wrote poetry in demotic Vietnamese, and so helped to found a national literature. A few cities in Vietnam have streets named after Hồ Xuân Hương.[3] WorksThe Jackfruit (Quả Mít, 果櫗)Source:[4]

The Cake That Drifts In Water (Bánh Trôi Nước, 𩛄𬈼渃)

The Unfortunate Plight of Women (Thân phận người đàn bà, 身份𠊛彈婆)

References

Sources

External links

|