|

Gush Katif

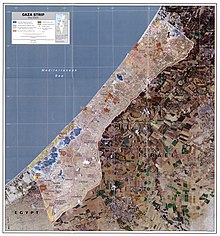

Gush Katif (Hebrew: גוש קטיף, lit. 'Harvest Bloc') was a bloc of 17 Israeli settlements in the southern Gaza Strip. In August 2005, the Israel Defense Forces removed the 8,600 Israeli residents from their homes after a decision from the Cabinet of Israel. The communities were demolished as part of Israel's unilateral disengagement from Gaza. Geography Gush Katif was on the southwestern edge of the Gaza Strip, bordered on the southwest by Rafah and the Egyptian border, on the east by Khan Yunis, on the northeast by Deir el-Balah, and on the west and northwest by the Mediterranean Sea. A narrow, one kilometer strip of land populated by Bedouins known as al-Mawasi lay along the Mediterranean coast. Most of Gush Katif was on sand dunes that separate the coastal plain from the sea along much of the southeastern Mediterranean. Two roads served Gush Katif: Road 230, which runs from the southwest along the sea from the Egyptian border at Rafiah Yam through Kfar Yam to Tel Katifa on the bloc's northern border, where it entered Palestinian-controlled territory, and Road 240, which also runs parallel to the sea approximately one kilometre inland, and upon which most of the settlements and traffic were located. Road 240's southern end turned south to reach Morag and continued to Sufah and the Shalom bloc of villages south of the Gaza Strip, while its northern end turned east to the Kissufim Crossing, and served as the main route into Gush Katif. These roads were forbidden to Palestinian Arab drivers. While Kfar Darom and Netzarim were originally accessed along the main road to Gaza City (known as "Tencher Road"), Israeli and Palestinian traffic was separated after the failure of the Oslo Accords and the Second Intifada. Netzarim was isolated as an enclave accessed only through the Karni crossing and the Sa'ad junction and in the latter years, only by IDF armored vehicles. In 2002, a bridge was built for Road 240 over the Tencher road to physically separate the two arteries and allow unobstructed travel for both Palestinian and Israeli traffic. Demographics About 8,600 residents lived in Gush Katif,[1] many of them Orthodox Religious Zionist Jews, though many non-observant and secular Jews also lived there. The three northernmost communities, Nisanit, Dugit and Rafiah Yam, were secular. The area also included several hundred Muslim families, mostly al-Mawasi Bedouins, who while technically Palestinian residents had freedom of movement within Israeli areas due to peaceful relations. Contrary reports have noted the severity of the restriction of movement for Palestinian residents.[2] HistoryJews and their Israelite ancestors lived in Gaza since Biblical times. Residents included medieval rabbis Rabbi Yisrael Najara, author of "Kah Ribon Olam", the popular Shabbat song, and Mekubal Rabbi Avraham Azoulai.[relevant?] Land for the village of Kfar Darom was bought in the 1930s and settled in 1946; it was evacuated following an Egyptian siege in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[citation needed] Gush Katif began in 1968, when Yigal Allon proposed founding two Nahal settlements in the center of the Gaza Strip. He viewed the breaking of the continuity between the northern and southern Arab settlements as vital to Israel's security in the area, which had been captured the previous year in the Six-Day War. In 1970, Kfar Darom was reestablished as the first of many Israeli agricultural villages in the area. Allon's idea was designed with five key areas (or 'fingers,' being called by some the "five-finger print") slated for Israeli settlements along the Gaza Strip. After the Egypt–Israel peace treaty and the dismantling of the fifth 'finger' (Yamit bloc) south of Rafah, the fourth (Morag) and third (Kfar Darom) strips were united into one bloc that would become known as Gush Katif. The second finger, Netzarim, was connected to Gush Katif until after the Oslo Accords, while the bloc on the dunes north of Gaza, which straddled the Green Line, was more a part of the Ashkelon area communities.[3] Throughout the 1980s new communities were established, especially with the influx of former residents of the Sinai. Most of the bloc's communities were established as agricultural cooperatives called moshavs, where the residents from each town would work in clusters of greenhouses just outside the residential areas. Economy In the bloc's greenhouses, technology was used to grow pest-free leafy vegetables and herbs aiming to meet health, aesthetic and religious requirements.[citation needed] Most of the organic agricultural products were exported to Europe. In addition, the community of Atzmona had Israel's largest plant nursery, and with 800 cows, the Katif dairy was the second largest in the country. Telesales and printing were other significant industries. Exports from the greenhouses, owned by 200 farmers,[4] came to $200 million per year[5] and made up 15% of Israeli agricultural exports.[6] The assets in Gush Katif were estimated at $23 billion.[7] Of Israel's exports, Gush Katif exported:

The Economic Cooperation Foundation, funded by the European Union, bought the greenhouses for $14 million and transferred ownership to the Palestinian Authority, so 4,000 Palestinian workers could keep their jobs. The money was paid for the greenhouse guts, such as the computerized irrigation systems, as the law in Israel only allowed for the government to pay for the land and structures, as these are not moveable.[9] Israel compensated the evacuees $55 million for the greenhouses and the land.[9] Former head of the World Bank, James Wolfensohn, gave $500,000 of his own money to the project.[10] The rest was contributed by Israeli philanthropists, including Mortimer Zuckerman, Lester Crown, and Leonard Stern. They bought the irrigation systems and other moveables, because, according to Zuckerman, "Without those, the Palestinians would not be able to make a go of running the greenhouses."[9] When the Israelis left Gaza, half of the greenhouses were dismantled by their owners before leaving because they doubted they would receive compensation.[11] Afterwards Palestinians looted the area, and 800 of 4,000 greenhouses were left unusable,[12][13] while, according to Wolfensohn, most were left intact.[14] Subsequently, the harvest, intended for export via Israel for Europe, was lost due to the Israeli restrictions on the Karni crossing which "was closed more than not", leading to losses in excess of $120,000 per day.[14] Economic consultants estimated that the closures cost the agricultural sector in Gaza $450,000 a day.[15] Israel closed the crossing citing security concerns. Palestinian attacks Although the Gush Katif settlements and the roads leading to it were guarded by the Israeli Army's Gaza Division, settlers were still vulnerable to attacks. During the First Intifada (1987–1990) in nearby Gaza City, the residents of Gush Katif were subject to frequent stoning of traffic, among other incidents. During the Second Intifada (2000-2005), Gush Katif was the target of thousands of attacks by Palestinian militants, with over 6000 mortars and Qassam rockets launched into the settlements. Though these attacks resulted in few deaths, they caused damage to property and psychological distress.[16][17] Most ground attacks were by Palestinian gunmen using infiltration tactics, including attempts by sea. Victims include an 18-year-old killed by a Palestinian sniper in November 2000,[18] and five teenagers who were fatally shot in March 2002 when terrorists infiltrated the Otzem pre-military academy in Atzmona.[18] Attacks on Israeli vehicles on the Kissufim road were common. Many of the ground attacks on Gush Katif were thwarted by the Israeli military, but fatal attacks included:

Evacuation On August 13, 2005, the Gush Katif region was closed to non-residents for the evacuation plan. Though effectively violating the Disengagement law, which most residents viewed as immoral and illegitimate,[24] most settlers did not voluntarily leave their homes or pack in preparation for eviction. On August 15, 2005, the forcible evacuation began. On August 22, 2005, the residents of the last settlement, Netzarim, were evicted. Many residents returned to pack the contents of their homes and the Israeli government began the destruction of all residential buildings. On September 12, 2005, the Israeli Army withdrew from each settlement up to the Green Line. All public buildings (schools, libraries, community centres, office buildings) as well as industrial buildings, factories, and greenhouses which could not be taken apart were left intact. Post-withdrawalIn Jerusalem, the "Gush Katif Museum" was founded to preserve the memory of the place.[25] At the time of the Gush Katif withdrawal, Israeli authorities destroyed all the Israeli residents' homes. Palestinians dismantled most of what remained, scavenging for cement, rebar, and other construction materials. There had been a public debate about the many public structures and synagogues in Gush Katif: "Many asserted that the buildings must be destroyed in order to ensure that they would not be used by terrorist organizations in the future. The fate of many of the area’s synagogues was also discussed at that time".[26] Originally, the Israeli cabinet had planned to destroy synagogues in the settlement, but the government responded to pressure from religious Jewish organizations and reversed its decision.[27][28] "Limor Livnat suggested involving UNESCO, with the hopes they would declare Gush Katif synagogues as official World Heritage Sites".[26] The synagogues were left intact, as the IDF did not wish to destroy holy sites and hoped that the Palestinians would respect these buildings. Most of the synagogues were destroyed by Palestinians immediately after the evacuation. Palestinians set fire to the buildings.[29] In 2007, it was reported that the synagogue sites were used for military training and rocket launches against Israel.[30] In July 2014, in Operation Protective Edge Israel sought to protect its residents from the barrage of rockets fired from Gaza and destroyed a network of tunnels aimed at Israel's southern communities and targeted Hamas bases, some of which were located where Gush Katif once stood.[31] Some Israeli politicians in the Knesset apologised for not realizing this would happen and not doing enough to prevent it.[32] Following the 2023 Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October, there has been a renewed campaign to return Israeli settlers to Gush Katif,[33] including Hanan Ben Ari singing “We return to Gush Katif” to Israeli troops.[34] Former settlements in Gush Katif

Most of the Gush Katif settlements were concentrated in one bloc on the southwest edge of the Gaza Strip and were individually surrounded by fencing. Former settlements north of Gush KatifThree Israeli settlements on the northern edge of the Gush Katif and another near its center were more detached:

The three former used Ashkelon services, while Netzarim was mostly self-sufficient. 2023 developmentsIn the context of the Israel–Hamas war of 2023–24, some Israelis have gathered in Yad Mordechai near the Gaza Israel border, in hopes of rebuilding Gush Katif.[35] In February of 2024, a group of Israeli settlers, some former residents of Gush Katif, gathered at the Beit Hanoun/Erez Crossing with construction materials and weapons with the same goal.[36] This effort has been conducted, at least in part, by Nachala Settlement Movement, which has successfully led efforts to in the past to build illegal settlements in the West Bank.[37] Supporters of the effort include Knesset member Ohad Tal, of the party Religious Zionism.[38] See alsoReferences

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Gush Katif.

|