|

Grimeton Radio Station

Grimeton Radio Station (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈɡrɪ̂mːɛˌtɔn])[1] in southern Sweden, close to Varberg in Halland, is an early longwave transatlantic wireless telegraphy station built in 1922–1924, that has been preserved as a historical site. From the 1920s through the 1940s it was used to transmit telegram traffic by Morse code to North America and other countries, and during World War II was Sweden's only telecommunication link with the rest of the world. It is the only remaining example of an early pre-electronic radio transmitter technology called an Alexanderson alternator. It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2004, with the statement: "Grimeton Radio Station, Varberg is an exceptionally well preserved example of a type of telecommunication centre, representing the technological achievements by the early 1920s, as well as documenting the further development over some three decades." The radio station is also an anchor site for the European Route of Industrial Heritage.[2] The transmitter is still in operational condition, and each year on a day called Alexanderson Day is started up and transmits brief Morse code test transmissions, which can be received all over Europe. HistoryBeginning around 1910 industrial countries built networks of powerful transoceanic longwave radiotelegraphy stations to communicate telegraphically with other countries. During the First World War radio became a strategic technology when it was realized that a nation without long-distance radio capability could be isolated from the rest of the world by an enemy cutting its submarine telegraph cables.[3] Sweden's geographical dependence on other countries' underwater cable networks, and the temporary loss of those vital connections during the war, motivated a decision in 1920 by the Swedish Parliament that the Royal Telegraph Agency build a "big radiotelegraphy station" in Sweden to transmit telegram traffic across the Atlantic.[3] At the time, there were several different technologies used for high power radio transmission, each owned by a different giant industrial company. Bids were requested from Telefunken in Berlin, The Marconi Company in London, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in New York and Société Française Radio-Electrique in Paris. The transmitter chosen was the 200 kW version of the Alexanderson alternator, invented by Swedish-American Ernst Alexanderson, manufactured by General Electric and marketed by their subsidiary RCA. This consisted of a huge rotating electromechanical AC generator (alternator) turned by an electric motor at a fast enough speed that it generated radio frequency alternating current, which was applied to the antenna. It was one of the first transmitters to generate sinusoidal continuous waves, which could communicate at longer range than the damped waves which were used by the earlier spark gap transmitters. The alternator was chosen because it was already used in most other transatlantic radio stations, reducing potential compatibility problems.[3] The fact that it was designed by a Swede may have also played a part.[3] After careful calculations, the station was located in Grimeton, on the southwest coast of Sweden nearest North America, which allowed good radio wave propagation conditions over the North Atlantic to America, and also Norway, Denmark, and Scotland.[3] The site was purchased in autumn 1922, construction began by the end of the year, and the station was finished in 1924.[3] Two 200 kilowatt Alexanderson alternators were installed, to allow maintenance to be performed on one without interrupting radio traffic.[4] To achieve daytime communication over such long distances, transoceanic stations took advantage of an earth-ionosphere waveguide mechanism which required them to transmit at frequencies in the very low frequency (VLF) range below 30 kHz. Radio transmitters required extremely large antennas to radiate these long waves efficiently. The Grimeton station had a huge multiply-tuned flattop antenna 1.9 km (1.2 miles) long consisting of twelve (later reduced to eight) wires supported on six 127 m (380 foot) high steel towers, fed at one end by vertical feeder wires extending up from the transmitter building. The station started operation in 1924, transmitting radiotelegraphy traffic with the callsign SAQ on a wavelength of about 18,000 metres (16.7 kHz),[4] later changed to 17,442 metres (17.2 kHz),[5] to RCA's Radio Central receivers on Long Island, New York. It immediately took over 95% of the Swedish telegram traffic to the United States.[3] The Alexanderson alternator technology was becoming obsolete even as it was installed. Vacuum tube electronic oscillator transmitters, which used the triode vacuum tube invented by Lee De Forest in 1907, replaced most pre-electronic transmitters in the early 1920s. However the large capital investment in an alternator transmitter caused owners to keep these huge behemoths in use long after they were technologically obsolete. By the mid-1930s most transatlantic communication had switched to short waves, and, beginning in 1938, vacuum tube shortwave transmitters were installed in the main building, using dipole and rhombic antennas in a neighbouring field. The Alexanderson alternator found a second use as a naval transmitter to communicate with submarines, as VLF frequencies can penetrate a short distance into seawater. During the Second World War 1939–1945, the station experienced a heyday, when it was one of Scandinavia's gateways to the outside world. Underwater communication cable connections had once again been quickly severed by nations at war and the radiotelegraphy transmissions were a link to the outside world. Several new transmitters were therefore added to the station. As users during the war included the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs and various embassies and legations, the radio station’s transmissions were subject to interception by signals intelligence operations such as the British Y service. Following the war, additional transmitters were installed and the number of destinations increased, reaching a peak in the 1950s when the station operated twelve shortwave transmitters and one electronic longwave transmitter (as well as the original Alexanderson system), maintaining traffic to some twenty different countries in Europe, Asia and the Americas. By that point, the telegraphic transmissions had shifted from Morse code to radioteletype and the station also provided radiofax and radiotelephony services. By the 1960s, many of the transmitters were beginning show their age and were subsequently decommissioned, being replaced by more modern equipment. However, rather than refitting the original station building, a new facility was built in 1966 to house the new transmitters, a move which allowed for the preservation of the older equipment. Several new antennas were also erected in the mid-to-late 1960s, but these investments were relatively short-lived in their original context as they coincided with the move away from using fixed radio stations for international communications in favour of satellites and new types of cables. Instead, focus would eventually shift to long-range maritime radio. Out of the original system, one of the alternator transmitters had been gradually dismantled and scrapped in the 1950s to free up space in the station building. The remaining alternator continued to be used for naval transmissions until the early 1990s, when a modern solid-state LF transmitter replaced it. Grimeton Radio Station is now the only station left in the transatlantic network of nine long wave stations that were built during the years 1918–1924, all equipped with Alexanderson alternators. In 2004 it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List. The Grimeton transmitter is the last surviving example of an Alexanderson alternator, the only radio station left from the pre-vacuum tube era, and is still in working condition. Each year, on a day called Alexanderson Day, either on the last Sunday in June, or on the first Sunday in July, whichever comes closer to 2 July, the site holds an open house during which the transmitter is started up and transmits test messages on 17.2 kHz using its call sign SAQ, which can be received all over Europe. Technical description

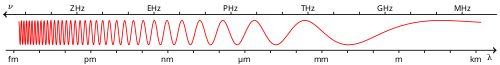

The electromechanical transmitter in Grimeton transmitted at a frequency of 17.2 kHz, i.e. in the VLF range, and was thus able to reach America. In principle, an electric generator (A) is used for this purpose. This is set in rotation by a motor (500 HP, 711.3 rpm) via a gearbox (setup ratio: 2.97) and thus generates a continuous sinusoidal AC voltage (B) of 17.2 kHz or 17,200 Hz. [6] For comparison, generators of the public electricity networks produce an alternating voltage of 50 or 60 Hz, depending on the country. To produce such high frequencies with a generator, a fast-rotating generator (2115 revolutions per minute) with a special design is necessary. In Grimeton, mainly Morse signals were transmitted. To send information with the generated alternating voltage, the texts to be sent are translated into a sequence of short and long pulses according to the Morse code by means of a Morse key (D). The switchgear (C) uses these pulses to control the transmission of the AC voltage to the antenna (F). When the key is pressed, the AC voltage is passed on to the antenna and transmitted from there. If the key is not pressed, the AC voltage is suppressed by the switchgear and no signal is transmitted. Thus, for example, as shown in (E), the letter A can be transmitted by a short and a long wave packet and detected at the receiver. The AC voltage generated has a voltage of 2000 volts [7] and a power of 200 kW [6] (although these days it is usually limited to about 80 kW). Such strong signals cannot be switched on and off by a simple switch, it would cause considerable sparking. In Grimeton, a different effect was used for this purpose. As known from historical radios, the antenna and the adjacent coils and capacitors form an resonant circuit, which must be tuned to the desired frequency so that the energy is optimally transmitted. In Grimeton, the tuning of this oscillating circuit is now disturbed in the switchgear (C) when the Morse key is not pressed, thus suppressing transmission. Thus it is possible to influence an AC power of 200kW with a small power (3 kW DC).

As usual in electric generators, an alternating voltage is generated in adjacent coils (B) in the generator (A) by means of rotating magnetic fields. In Grimeton, these coils are mounted on the stator, divided into 2x32 sectors, on both sides to the rotor. The individual windings of a sector are connected to corresponding primary windings (C) of the transformer (D). When the primary voltages are transmitted to the secondary winding (E) of the transformer, these voltages are superimposed to form a strong, sinusoidal output signal which is output to the antenna and transmitted. The control winding (F) and the magnetic amplifier (G) are responsible for controlling the transmission process by the Morse key (H). The magnetic amplifier is an arrangement of coils and capacitors whose AC resistance is indirectly influenced by the Morse key and a DC source. When the Morse key is open, the solenoid amplifier short-circuits the control winding (F), to put it simply. The short-circuiting of (F) disturbs the transmitting oscillating circuit, so that finally no more than 9 % of the normal antenna current flows [2, page 53]. The situation described above (full transmit or no transmit at all) can therefore only be achieved approximately, but this is sufficient in practice.

The above sketch is not to scale, the air gap between rotor and stator frame is only 1mm wide.[8] The rotor is a steel disc measuring 1.6 m in diameter and approximately 7.5 cm thick at the periphery. Antenna systemTo achieve maximum range, like other transoceanic radiotelegraphy stations of this era it transmitted in the VLF band, at a frequency of 17.2 kilohertz and so the wavelength is approximately 17442 meters. Even though the antenna is approximately 2 km long, it is short compared with the wavelength and so it is not very efficient. The antenna system consists of antenna wires supported by masts, such as those used for high-voltage power lines. The six antenna masts each have a 46m cross-arm at the top and are 127m high. Today they carry 8 antenna conductors although originally there were 12. The multiple-tuned antenna used at Grimeton is a pre-WW1 invention by E F W Alexanderson, which uses a number of vertical radiator wires interconnected by the flat-top wires, which serve both as top capacitance and as a high-voltage transmission line. Each vertical wire is terminated in a ground-mounted tuning inductance (or "coil") which serves to tune out the capacitive reactance of the wire, and to establish the proper phase relationship between the currents in the wires. By dividing the total current flowing into the ground or counterpoise system between several connection points, the equivalent ground loss resistance may be substantially reduced compared to the case when all current is fed into a single vertical radiator. This increases the antenna efficiency by about an order of magnitude. Gallery

See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Varberg Radio Station. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||