|

Governor's Body Guard of Light Horse

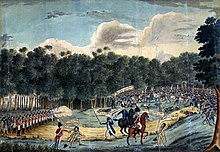

The Governor's Body Guard of Light Horse was a military unit maintained in the Colony of New South Wales between 1801 and 1834, and reputedly the "first full-time military unit raised in Australia".[1] It was established by Governor Philip Gidley King by drawing men from the New South Wales Corps, the British garrison in the colony. Normally consisting of one or two non-commissioned officers and six privates, the Guard provided an escort to the governor and carried his despatches to outposts across the colony. From 1802, the men of the Guard were drawn from convicts pardoned by King. Men from the unit were deployed during the Castle Hill convict rebellion of 1804 and a trooper of the Guard assisted in the capture of two of the rebel leaders. After King was succeeded by William Bligh in 1806, the Guard reverted to being drawn from the New South Wales Corps. The unit seems to have been absent during the Corps' 1808 mutiny against Bligh and, by one report, supported it. It was ordered to disband by the Earl of Liverpool but was granted a reprieve in 1812 by Liverpool's successor Earl Bathurst. Viscount Goderich ordered disbandment again in 1832 and Governor Richard Bourke transformed the unit into the Mounted Orderlies in 1834. These were absorbed into the New South Wales Mounted Police in 1836 and continued as a separate component within that force until at least 1860. Formation The Guard was raised in the British Colony of New South Wales in late 1800 at the initiative of Governor Philip Gidley King. An order was sent from King to Lieutenant Colonel William Paterson of the New South Wales Corps on 26 December 1800 requiring the corps to provide a non-commissioned officer (NCO) and six privates to act as a bodyguard to King. King intended to utilise the men as messengers to carry despatches and specified that the men must be capable of riding a horse. Six men and a corporal were identified, some of whom had served in cavalry regiments, and these were serving in the role by early 1801. King provided horses and cavalry equipment from colony government funds and authorised a 1 shilling per day pay rise to the corporal and 6 pence to the privates.[2] The Guard wore the British light dragoon uniform throughout its service and was armed with the pattern 1796 light cavalry sabre.[1][3][4] Historian Clem Sargent described the unit as "one of the lesser known of the military organisations in the early history of the Colony of New South Wales".[2] Its obscurity may derive from its informal origins; being raised by the governor without authority from Whitehall and never authorised by the War Office, the men remained formally members of their original units.[2] According to Sargent, the Guard was the "first full-time military unit raised in Australia".[1] The Guard carried the governor's despatches sent to far-flung garrison outposts across the colony and was particularly busy in the early years due to unrest among newly arrived Irish convicts. Many of these men were Republican revolutionaries, members of the Society of United Irishmen sentenced to transportation following capture after the 21 June 1798 Battle of Vinegar Hill. By 1 March 1802, the unit had dwindled to just the corporal and four privates.[2] Use of pardoned convicts From 12 October 1802, the men of the Guard ceased to be drawn from the New South Wales Corps, possibly as a result of a disagreement between King and Paterson. Instead, King drew members from prisoners in good standing, whom he pardoned – a move that upset Paterson.[5][6] King clashed frequently with the members of the New South Wales Corps over their monopoly on the trade in rum and misuse of convict labour.[7] In 1801, King prevented the landing of 58,000 imperial gallons (260,000 L; 70,000 US gal) of alcohol. A series of disputes culminated in the wounding of Paterson in a duel with one of his captains, John Macarthur, who was heavily involved in the rum trade.[8] King sent Macarthur to England to face trial, but the advocate-general refused to hear the case and Macarthur was freed.[9] King's employment of ex-convicts in the Guard was known to the Colonial Office in London and appears to have received tacit sanction, despite the irregularity of such an arrangement. Historian David Clune notes that because of King's efforts to restrict the rum trade, safeguard the colony's women, children and aborigines, and stamp out corruption in use of convict labour and land grants, the Guard was "viewed more with amusement than anger in London".[8] King placed the Guard under the command of Captain John Piper of the New South Wales Corps in February 1803 to assist with the recapture of escaped convicts near Parramatta. Piper refused to make use of the men and ordered them to remain at Government House in Sydney. This angered King who complained to Major George Johnston, commanding the corps while Paterson was ill. Johnston replied that the men of the Guard could not be considered soldiers as they were not subject to the Articles of War and also questioned if they were reliable enough to have earned their pardons. King's reply stated that the men were as respectable as those in the New South Wales Corps, at least seventy of whom were also former convicts. The disagreement ended with the replacement of Piper as commandant at Parramatta by Captain Edward Abbott; the convicts were recaptured and two were executed. Major Johnston himself later made use of the Guard and commented favourably upon their conduct.[5] Despite rumours of impending revolt among the Irish convicts, the remainder of 1803 was quiet for the Guard.[10] That November, King pardoned George Bridges Bellasis, a former lieutenant in an East India Company artillery unit who had been transported for killing a fellow officer in a duel. King granted Bellasis the rank of a lieutenant of artillery and placed him in command of the Guard.[5] Castle Hill convict rebellion Unrest among the Irish convicts led to the Castle Hill convict rebellion, which broke out at 8 pm on 4 March 1804.[5][10] The convicts were headed for Parramatta and King, with his provost marshal and four men of the Guard, set out for that settlement immediately. One trooper of the Guard was sent to carry orders to Major Johnston who was at his house in Annandale. Johnston was to assemble forces to intercept the convicts.[10] The convicts retreated ahead of Johnston's force, through Toongabbie, but were caught at Castle Hill before they could reach the Hawkesbury. Johnston, intending to delay the convicts whilst he assembled his forces, sent the Guard's Trooper Anlezark to parley with them. The convicts removed Anlezark's pistol flints, rendering his weapons useless, but allowed him to return unharmed. Johnston decided to speak with the convict leaders in person, accompanied by Anlezark. The convicts refused to surrender and began forming up on a nearby hill, later nicknamed Vinegar Hill. Johnston requested another meeting with the convicts at which he and Anlezark drew their pistols and seized two of the convict leaders.[10][11] Men of the New South Wales Corps then advanced on the hill. The convicts were quickly defeated and the rebellion ended.[12][13] The next day, Johnston wrote to King that there had been 250 "Runaways" and his force had "been under the necessity of killing nine and wounding a great many – the number we cannot ascertain. We have taken 7 prisoners and 7 stand of Arms, and other Weapons ...".[11] Among others, his letter mentioned "the two Troopers" favourably.[11] The battle, which became known as the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill, is illustrated in a contemporary painting now in the collection of the National Library of Australia. The painting depicts Anlezark (erroneously shown as a corporal) drawing his pistol and ordering a rebel leader: "Croppy lay down".[12] Anlezark, a convicted burglar and fourteen-year British Army cavalry veteran, was promoted to corporal in the Guard in May 1804, replacing the existing NCO who was discharged for "gross abuse to a superintendent".[3] The Guard's actions in quelling the rebellion and a favourable report from Johnston led King to propose increasing the unit to thirty men. It seems this was never implemented; such an action required the approval of the British colonial secretary, which was not forthcoming.[3] Bligh and the Rum Rebellion King was succeeded as governor by William Bligh in August 1806. Bligh immediately set about reforming the colony, banning the use of rum as a de facto currency. However, this action, together with his bad temper and blunt manner, made him many enemies, including Macarthur who had returned to New South Wales.[14] Bligh arrested Macarthur in early January 1808 for violating the alcohol-related import restrictions. Johnston, who now commanded the New South Wales Corps in Sydney, marched on Government House and arrested Bligh in an act known as the Rum Rebellion.[15] It is unclear where the men of the Guard were during Bligh's arrest but the unit had reverted to being provided from men of the New South Wales Corps and, given the men's divided loyalties, probably chose to absent themselves on the day of the rebellion.[3] Bligh's provost marshal William Gore, who was also arrested, later recalled being visited by members of the Guard during his imprisonment and alleged that Macarthur, who set himself up as colonial secretary, was attended by two members of the unit.[3] Later service Lachlan Macquarie, dispatched by the British government to assume the office of governor and restore order, arrived in the colony in December 1809.[15] The New South Wales Corps, renamed the 102nd Regiment of Foot, was recalled to Britain and replaced by the 73rd Regiment of Foot, which arrived on 1 January 1810.[16] By April of that year the Guard consisted of a sergeant, a corporal and six troopers. One trooper had survived from King's administration, but the majority were former New South Wales Corps men who had transferred to the 73rd Regiment. At this time the supplementary pay, funded by the colonial government, was 1 shilling 6 pence per day for the sergeant, 1 shilling for the corporal and 6 pence for the troopers.[17] During his term, Macquarie authorised the construction of a brick-built barracks and stables, with capacity for sixteen horses, in Sydney for the Guard.[18] Macquarie saw the advantages of the unit in carrying despatches and in providing personal protection to "visit distant Interior parts of the Colony, or penetrate into the Wild Jungles and Forests of it, inhabited by Savages, Who probably Might be induced to take a treacherous Advantage of his Unprotected Situation, Were he to go Amongst them without a Guard".[17] He sought to increase their strength to twelve men but when news of this reached the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Earl of Liverpool, he refused to grant permission and demanded the unit be disbanded. In 1812, Macquarie requested this decision be rescinded as most other British colonies had a unit of regular or militia cavalry at their disposal; he claimed that he "felt very much hurt" at being "singled out as Undeserving this Honor".[17] Macquarie maintained the unit until it was approved later in 1812 by Liverpool's successor, the Earl Bathurst.[17][19] Bathurst also sanctioned an increase in size to twelve troopers, plus the sergeant and corporal.[19] Despite Bathurst's permission being granted, the unit's nominal strength remained at eight men until the end of Macquarie's tenure in 1821. The unit was kept up to strength with replacements drawn from the British regiment on garrison duty in the colony which, from 1817, was the 48th Regiment of Foot.[19] The Guard's duties at this time included escorting the governor on visits around the colony and announcing guests at the governor's balls.[19][20] The Guard sergeant from 1808 to 1822 was Charles Whalan who became good friends with Macquarie, accompanying him on personal holidays and being one of the last people to see him off on his return to Britain in 1821.[21] Disbandment The Guard survived through the governorships of Thomas Brisbane (1821–25) and Ralph Darling (1825–31). When newly arrived governor Richard Bourke disclosed an expenditure of £112 16s 6d in his December 1831 report, this was queried by the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Viscount Goderich, who ordered the unit disbanded.[20][22] Bourke, who considered the full title of the Guard as "much too lofty for so trifling an establishment",[1] responded by establishing the Mounted Orderlies as a replacement in 1834.[1][20] These were drawn from the New South Wales Mounted Police, and commanded by Bourke's aide-de-camp.[20] Upon learning of this, Goderich ordered their disbandment.[1] Bourke transferred the unit to the New South Wales Mounted Police on 1 July 1836 and they continued to serve the governor until at least 1860.[1][23] Sargent notes that the ambiguous status of the Governor's Body Guard of Light Horse was indicative of the difficulty the British government had in understanding the colony in this period. The British were keen to restrict expenses incurred by the government of the colony and, without an understanding of the local conditions, saw no reason for the governor to have a personal bodyguard.[1] References

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||