|

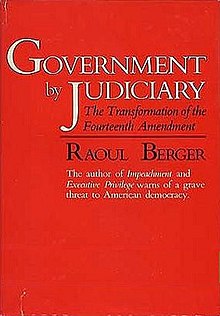

Government by Judiciary

(publ. Harvard University Press) Government by Judiciary is a 1977 book by constitutional scholar and law professor Raoul Berger which argues that the U.S. Supreme Court (especially, but not only, the Warren Court) has interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution contrary to the original intent of the framers of this Amendment and that the U.S. Supreme Court has thus usurped the authority of the American people to govern themselves and decide their own destiny.[1] Berger argues that the U.S. Supreme Court is not actually empowered to rewrite the U.S. Constitution – including under the guise of interpretation – and that thus the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently overstepped its designated authority when it used its powers of interpretation to de facto rewrite the U.S. Constitution in order to reshape it more to its own liking.[1] (By de facto rewriting the U.S. Constitution, Berger means that the U.S. Supreme Court didn't actually alter the text of the US Constitution but nevertheless interpreted it in such a way that the U.S. Supreme Court altered the meaning and/or the effects of the relevant parts of the U.S. Constitution.)[1] Summary   In this book, Berger argues that the Fourteenth Amendment should be interpreted based on the original intent of its draftsmen.[1] Berger argues that this is how the U.S. Constitution was historically interpreted as well as how the draftsmen of the 14th Amendment intended for this Amendment to be interpreted.[1] Berger also argues that the sole purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to constitutionalize the Civil Rights Act of 1866.[1] (Berger rejects the use of statements by critics of the Fourteenth Amendment to advance a broad reading of the Fourteenth Amendment by arguing that these statements were made to make the Fourteenth Amendment look terrifying in order to increase the odds that this Amendment be rejected and defeated.[1]) Specifically, the purpose of that Act was to tear down the Black Codes in the post-Civil War Southern U.S. and to give the freedmen basic rights such as freedom of contract, the right to sue and be sued, to travel and work wherever they please, and to buy, sell, and own property.[1] Berger argues that, in the view of its draftsmen, the 1866 Civil Rights Act did not require U.S. states to allow African-Americans to serve on juries, to vote, to intermarry with White people, or to go to the same schools that White people went to.[1] Thus, Berger argues that numerous U.S. Supreme Court decisions based on the Fourteenth Amendment have been wrongly decided since they were decided contrary to the original intent of the Fourteenth Amendment.[1] These decisions include the 1880 case Strauder v. West Virginia (which stated that African-Americans cannot be prohibited from serving on juries), the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education (which struck down school segregation), the 1960s one person, one vote cases such as Reynolds v. Sims, and the 1967 case Loving v. Virginia (which struck down bans on interracial marriage).[1] Berger also criticizes the argument made by Alexander Bickel, William Van Alstyne, and others that the 14th Amendment's language was meant to be open-ended in order to give future generations a large amount of discretion in determining how to apply the 14th Amendment's principles to their own times.[1] Berger argues that the "open-ended language" theory lacks any historical basis whatsoever and that, in any case, any intentions that existed but were not disclosed to the American people before they ratified a constitutional amendment certainly have no value and shouldn't be used as a basis for interpreting this amendment.[1] In Berger's view, the ideas of substantive due process as well as the incorporation of the Bill of Rights (against the states) are both contrary to the intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment.[1] In regards to incorporation of the Bill of Rights, Berger argues that the views of John Bingham and Jacob Howard in regards to this issue were unorthodox (Bingham and Howard both stated that the 14th Amendment would apply the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights against the states) and that most Republicans in the 39th United States Congress (which proposed and passed the 14th Amendment) did not share Bingham's and Howard's views on this issue.[1] As support for his position, Berger points out that none of the Republicans who spoke about the 14th Amendment on the campaign trail leading up to the 1866 elections ever said or even suggested that the 14th Amendment would apply any of the amendments in the Bill of Rights against the states and that court rulings shortly after the 14th Amendment's ratification in 1868 continued to hold that the Bill of Rights was inapplicable against US states (as opposed to the US federal government—against which the Bill of Rights was always held to be applicable).[1] Finally, Berger defends the holding in the notorious 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson and argues that the reason that "Plessy has become a symbol of evil[] ... is because we impose 'upon the past a creature of our own imagining' instead of looking to 'contemporaries of the events we are studying.'"[1] Berger argues that "Plessy merely reiterated what an array of courts had been holding for fifty years"—starting with the 1849 Massachusetts Supreme Court case Roberts v. City of Boston (which upheld the constitutionality of segregated schools in Massachusetts).[1] Berger supported the idea of US constitutional change through the Article V amendment process but did not believe that the US judiciary actually had the authority to de facto amend the US Constitution under the guise of interpretation outside of the Article V amendment process—including when achieving change through the Article V amendment process looked extremely unrealistic.[1][2] Berger believed that not every injustice actually has a judicial remedy and that therefore the fact that an injustice exists does not automatically mean that the U.S. federal judiciary actually has the authority to eliminate this injustice.[1] Also, Berger argues that the U.S. Congress and not the courts were meant to have the exclusive authority to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment.[1] In Berger's view, the courts would only be allowed to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment if the U.S. Congress was to delegate this authority to them.[1] Berger points out that, at the time of the 14th Amendment's drafting and ratification in the late 1860s, there was still widespread distrust of judicial review among Northerners and abolitionists due to them still remembering that the antebellum U.S. judiciary had generally not ruled in favor of abolitionists but instead made various pro-slavery rulings such as Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Dred Scott v. Sandford that strongly incensed abolitionists.[1] AftermathAfter this book was published, Berger spent twenty years responding to his critics – writing "forty article-length rebuttals and one of book length."[1] The scholars and law professors whom Berger responded to include (but are not limited to) John Hart Ely, Aviam Soifer, Louis Fisher, Michael Kent Curtis (author of Free Speech, "The People's Darling Privilege"), Paul Brest, Paul Dimond, Lawrence G. Sager, Mark Tushnet, Michael Perry, Gerald Lynch, Hugo Bedau, Robert Cottrol, Michael W. McConnell, H. Jefferson Powell, Jack Balkin, Leonard Levy, Stephen Presser, Michael Zuckert, Randy Barnett, Boris Bittker, Bruce Ackerman, Hans Baade, Akhil Amar, Jack Rakove, and Ronald Dworkin.[1] ReceptionAfter it was published, Government by Judiciary received reviews from publications such as Duke Law Journal, Valparaiso University Law Review, Cornell Law Review, Columbia Law Review, and Commentary.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Since its publication in 1977, Government by Judiciary has been cited over 2,100 times.[9] See alsoReferences

Further reading

|