|

Gold mining in Colorado

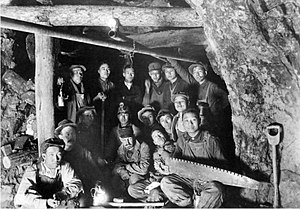

Gold mining in Colorado, a state of the United States, has been an industry since 1858. It also played a key role in the establishment of the state of Colorado. Explorer Zebulon Pike heard a report of gold in South Park, present-day Park County, Colorado, in 1807.[1] Gold discoveries in Colorado began around Denver; prospectors traced the placer gold to its source in the mountains west of Denver, then followed the Colorado Mineral Belt in a southwest direction across the state to its terminus in the San Juan Mountains. The Cripple Creek district, far from the mineral belt, was one of the last gold districts to be discovered and is still in production. Denver-area placers On June 22, 1850, a wagon train bound for California crossed the South Platte River just north of the confluence with Clear Creek and followed Clear Creek west for six miles (9.7 km). Lewis Ralston dipped his gold pan into a stream flowing into Clear Creek and found about a quarter of a troy ounce (worth almost $5, equivalent to $180 today) in his first pan. John Lowery Brown, who kept a diary of the party's journey from Georgia to California, wrote on that day: "Lay bye. Gold found." In a notation above the entry, he wrote, "We called this Ralston's Creek because a man of that name found gold here." Ralston continued to California, but returned to 'Ralston's Creek' with the Green Russell party eight years later. Members of this party founded Auraria (later absorbed into Denver City) in 1858 and touched off the gold rush to the Rockies. The confluence of Clear Creek and Ralston Creek, the site of Colorado's first gold discovery, is now in Arvada, Colorado.[2]: 6–7 A gold discovery in 1858 in the vicinity of present-day Denver sparked the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. In 1858, prospectors focused on the placers east of the mountains in the sands of Cherry Creek, Clear Creek, and the South Platte River. However, the placer deposits on the plains were small, and when the first rich discoveries were made in early 1859 in the mountains farther west, the miners abandoned the placers around Denver. Although the economic portions of the gold placers around Denver were quickly exhausted, producers of construction aggregate in the area sometimes recover small amounts of gold from their sand and gravel washing. The plains counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Douglas, Denver, Elbert and Jefferson are each credited with having produced small amounts of gold.[3] Central City-Idaho Springs district On January 5, 1859, during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush, prospector George A. Jackson discovered placer gold at the present site of Idaho Springs, where Chicago Creek empties into Clear Creek. It was the first substantial gold discovery in Colorado. Jackson, a Missouri native with experience in the California gold fields, was drawn to the area by clouds of steam rising from some nearby hot springs. Jackson kept his find secret for several months, but after he paid for some supplies with gold dust, others rushed to Jackson's diggings. The settlement was later renamed Idaho Springs, after the hot springs.[4] In May 1859, John H. Gregory found a gold-bearing vein (the Gregory Lode) in Gregory Gulch between Black Hawk and Central City. Within two months, many other veins were discovered, including the Bates, Gunnell, Kansas, and Burroughs.[5] Other early mining towns in the district included Nevadaville and Russell Gulch. Hardrock mining boomed for a few years, but then declined in the mid-1860s as the miners exhausted the shallow parts of the veins that contained free gold and found that their amalgamation mills could not recover gold from the deeper sulfide ores.[6] Nathaniel P. Hill built Colorado's first successful ore smelter in Blackhawk in 1868. Hill's smelter could recover gold from the sulfide ores, an achievement that saved hardrock mining in the district. Other smelters were built nearby. Through 1959, the district produced about 6,300,000 troy ounces (200 t), mostly from sulfide veins in gneiss and granodiorite.[1] The early gold discoveries were at the northeast end of the Colorado Mineral Belt, a large alignment of mineral deposits that stretches northeast-southwest across the mountainous part of Colorado. From Idaho Springs, prospectors followed the Colorado Mineral Belt west along Clear Creek, then over the mountain passes to South Park and to the headwaters of the Blue River. Breckenridge district Placer gold was discovered in the Breckenridge, or Blue River district, in 1859 at Gold Run by the Weaver Brothers, at Georgia, American, French, and Humbug Gulches on the Swan River, on the Blue River itself, and at the confluence of French Gulch and the Blue River.[2]: 22 Harry Farncomb found the source of the French Gulch placer gold on Farncomb Hill in 1878. His strike, Wire Patch, consisted of alluvial gold in wire, leaf and crystalline forms. By 1880, he owned the hill. Farncomb later discovered a gold vein, which became the Wire Patch Mine. Other vein discoveries included Ontario, Key West, Boss, Fountain, and Gold Flake.[2]: 57 Lode deposits were developed in the 1880s, as prospectors followed the gold to its source veins in the hills. Gold in some upper gravel benches north of the Blue River was recovered by hydraulic mining. Gold production decreased in the late 1800s, but revived in 1908 by gold dredging operations along the Blue River and Swan River. The Breckenridge mining district is credited with production of about 1,000,000 troy ounces (31 t) of gold.[7] The gold mines around Breckenridge are all shut down, although some are open to tourist visits. The characteristic gravel ridges left by the gold dredges can still be seen along the Blue River and Snake River, and the remains of a dredge are still afloat in a pond off the Swan River. South Park districts  Prospectors discovered rich placer deposits on the west side of South Park in 1859. The deposits were in valleys on the east side of the Mosquito Range. The town of Alma, Colorado, the heart of this district, was established on December 2, 1872 by miners working the area, though that area had been actively mined since 1860.[8] The principal districts were the Alma-Fairplay district on the headwaters of the South Platte River, and the Tarryall district along Tarryall Creek northwest of Como, Colorado. Important lode gold deposits were later discovered above Alma. A floating dredge worked the floor of the South Park valley east of Fairplay from 1941 to 1952, leaving the distinctive gravel ridges that can still be seen. Production from the Tarryall district was 67,000 troy ounces (2.1 t), almost all from placers. The Alma-Fairplay district produced 1,550,000 troy ounces (48 t), more than two-thirds of which came from lode deposits.[9]  Before any prospectors in Park County began excavating the mountains, they used placer mining to extract gold from the local waterways. Placer mines began to appear all over Park County after 1861. Placer gold was found in Tarryall, Fairplay, Alma, Breckenridge, and Leadville.[10] A notable amount came from the beds of the South Platte River.[11] Many placer claims existed to the south and west of Alma.[10] The mining town of Montgomery in Hoosier Pass had another small placer gold operation in 1911.[10] Two notable placer mines in the Alma mining district are Snowstorm, home of the famous Snowstorm Dredge, and Cincinnati.[10] In 1882, the Alma Placer Mining Company owned roughly 640 acres of placer mines.[11] The only hindrance is that this type of mining can only be conducted during the short summer months. After prospectors established placer mines all over Park County's gulches, they moved on to the more difficult mountain veins to plunge the depths for riches. Lode mining costs more than surface mining, and there are also significant risks to this method including a loss of air supply, explosions, and implosions.[12] Like everyone who came West had hoped, gold was found in the lode mines. The first lode mine in the Alma district was located in Buckskin Gulch, and it was explored by local icon Joseph Higginbottoms, aka Buckskin Joe.[13] That first claim was called the Phillips Lode Mine. In the first two years, the mine produced $300,000 worth of ore.[13] Once the gold had dried up in Buckskin Gulch, they moved on to quartz.[13] Paris Mine, also located off Buckskin Gulch, is another lode mine producing oxidized gold.[14] Off Mosquito Gulch, the London Lode Mine produced gold, silver, and copper. Magnolia Mine in Montgomery was well known for producing gold, lead, silver, and copper, but it also produced quartz, pyrite, and limonite.[15] Leadville districtThe history of the Leadville district began in April 1860, with one of the richest discoveries of Colorado placer gold at California Gulch, the site of Oro City.[2]: 23 [16] Another rich discovery was made at McNulty Gulch along the headwaters of Tenmile Creek.[2]: 24 The placers were exhausted within four years, but lode gold was discovered in 1868. The gold discoveries led to the discovery of the silver deposits in 1877, and the founding of the city of Leadville. The Little Johnny silver and lead mine, dating from 1879, was further developed in 1893, by John F. Campion and James Joseph Brown, which resulted in the production of large deposits of high-grade gold-copper ore.[2]: 60–61 The Leadville district produced 3,200,000 troy ounces (100 t) of gold, mostly as a byproduct of silver mining.[17] Summitville districtProspectors found placer gold in 1870 in the Wrightman Fork of the Alamosa River. Gold veins were discovered in 1871, and large-scale production started in 1875 after the construction of a mill. By 1880, the Little Annie vein helped make Summitville Colorado's largest gold producer. Over 100,000 ounces of gold were produced by 1890.[2]: 60 Operations were continuous until 1906, then sporadic after that.[18] Gold production up to 1990 was 520,000 troy ounces (16 t).[19] In 1985, Summitville Consolidated Mining Company, a subsidiary of Galactic Resources of Vancouver, British Columbia started open pit heap-leach mining at the Summitville mine. Mining ceased in 1992, and remediation started. However, Galactic Resources declared bankruptcy in December 1992, and the US Environmental Protection Agency stepped in to prevent releases of pollution from the property.[20] The EPA declared it a federal Superfund site in May 1993.[21] The total cost of environmental cleanup at the site has been estimated to be between $100 and $120 million (equivalent to between $220 and $260 million today).[22] In 1998, the general manager and the environmental manager of the mine pleaded guilty to federal pollution charges, and were each sentenced to six months probation and $20,000 fines (equivalent to $37,000 today).[23] Sneffels-Red Mountain-Telluride districtThe Sneffels-Red Mountain-Telluride district, in San Miguel and Ouray counties at the southwest end of the Colorado Mineral Belt, was discovered in 1875. Thomas Walsh developed the Camp Bird Mine in 1896.[2]: 84–91 The district is within and adjacent to a Tertiary volcanic caldera. Deposits are chimneys and veins in Tertiary volcanics and intrusives, and in older sedimentary rocks. Production through 1959 was 6,800,000 troy ounces (210 t) of gold, as well as considerable silver, lead, and copper.[19] Cripple Creek district "Part-time cowboy and full-time drinker" Robert Womack found gold float in 1879, which led him to digging countless prospecting holes in an attempt to find its lode, earning him the name "Crazy Bob".[25] His efforts finally paid off in 1890, when he found the El Paso lode. Winfield Scott Stratton discovered what became his Portland Mine at the site of Victor. By 1893, 10,000 miners working the district produced one third of Colorado's gold output. Gold cyanidation was introduced in 1895, and used alongside chlorination in the mills for gold extraction. By 1895, half of Colorado's gold production of 660,000 ounces came from the district. In 1897, half a million Troy ounces of gold was produced, and in 1900, 900,000 troy ounces, two thirds of the US output. By 1920, 41 mines were active, and cumulative gold production was over 500 tons.[2]: 66, 69, 72, 81 Located a few miles southwest of Pike's Peak, the Cripple Creek district wasn't discovered until later in the "rush", which was known as the "Pike's Peak Gold Rush", because Pike's Peak was a landmark visible 100 mi (160 km) out on the plains. The towns of Cripple Creek and Victor were established to serve the mines and miners of the district. Among the principal mines were the Mollie Kathleen Gold Mine at Cripple Creek and Stratton's Independence mine, at Victor, Colorado. Gold production up to 1990 was 21,000,000 troy ounces (650 t) worth about US$17 billion at 2008 prices)[clarification needed], making it the most productive gold-producing district in Colorado,[19] and the third-most productive in the United States (after Carlin, Nevada and Lead, South Dakota). Many of the mines in the district were quite deep and difficult to drain. The almost five-mile (8.0 km) Roosevelt Tunnel was a mine drainage tunnel dug between 1907 and 1919 below the Cripple Creek area to drain the mines and simplify ore haulage.[26][27] The Cripple Creek mining district covers a Miocene volcanic caldera filled with quartz latite porphyry. The ore bodies are veins and replacement zones within the quartz latite. The ore minerals are gold and silver tellurides, with accessory fluorite. The Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company formed in 1976 as a joint venture to restart mining in the district. From 1976 to 1989, the company produced 150,000 troy ounces (4.7 t) of gold by reprocessing tailings and mining two small surface deposits. The Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company began the first large-scale open pit mining in the district in 1994.[28] The Cresson mine open pits are located a few miles north of Victor. Mining continues today under the ownership of Newmont Corporation, which boosted gold production from 211,000 troy ounces (6.6 t) in 2014 to 451,000 troy ounces (14.0 t) in 2017, and 322,000 troy ounces (10.0 t) in 2019.[29][30] Some miners who worked in this district died in different ways including flu, pneumonia, in the mine, at home, or suicide. A list of dead miners has been recorded in a small notebook labeled "Dead". A photocopy of the notebook is held by the Cripple Creek District Museum.[31] Gold mining today Colorado gold production was 270,000 ounces in 1892, 660,000 ounces in 1895, peaked in 1900 at 1,400,000 ounces, and reached over one million ounces in 1916 for the last time. Gold production in 1922 was 300,000 ounces, and 200,000 ounces in 1928. The Gold Reserve Act helped increase production to 370,000 ounces in 1936. Production was 380,000 ounces, before the War Production Board limitation order L-208 stopped gold mining in 1942. Production restarted after World War II with 168,000 ounces in 1947. Gold production was 66,000 ounces in 1960 and 22,000 ounces in 1967. Production reached 37,000 ounces in 1972 and 72,000 ounces in 1978.[2]: 60, 69, 98, 101, 108, 111, 114, 118, 121, 123 Only one Colorado mine continues to produce gold, the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine at Victor near Colorado Springs, an open-pit heap leach operation owned by Newmont Corporation, which produced 322,000 troy ounces of gold in 2019 and reported 3.45 million troy ounces of Proven and Probable Reserves as at December 31, 2019.[29][30] See alsoReferences

External links |

||||||||||||||||||