|

Geremia Discanno

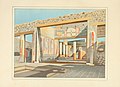

Geremia Discanno (sometimes spelled Di Scanno) (20 May 1839 – 14 January 1907) was an Italian genre and landscape painter,[1] who collaborated with archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli, art historian Emil Presuhn, and Naples-based chromolithographer Victor Steeger, to record wall paintings in the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum that were being excavated at the time. Early lifeDiscanno was born on 20 May 1839 in Barletta, a city in southeastern Italy near the site of the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC between the Romans and the Carthaginians led by Hannibal. His father, Gennaro Discanno, was a successful painter of ecclesiastical commissions who lived with his family in the wealthiest district of the city near the intersection of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele and the Corso Garibaldi, just around the corner from the birthplace of another famous painter and contemporary, Giuseppe De Nittis.[2] Barletta at the time of the Bourbons, and in particular during the reign of Ferdinand II, nicknamed the "Bomb King" for having his own subjects cannonaded, was an extremely class-oriented city and those who could afford it gathered regularly near Discanno's home beneath the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher with its bronze Colossus of Heraclius in front. Situated on the Adriatic coast, Barletta's port thrived as a point of embarkation for the privileged traveling to or returning from the east.[3] Both Discanno's father and the father of De Nittis, Raffaele, were publicly outspoken in their opposition to the Bourbon monarchy and their support for the unification of Italy. Raffael was imprisoned for two years while Gennaro, Discanno's father, suffered only a one-year sentence to a spiritual retreat in a monastery of Capuchin friars because of his relationships with the church and local clergy.[2] Professional trainingAs a rich landowner, De Nittis, could afford to have his son study with a local acclaimed artist, Giovan Battista Calò, who tutored other notable Barlettan painters including Vincenzo De Stefano, Giuseppe Gabbiani, and Raffaele Girondi.[4] But Discanno learned instead from his father at home. Geremia Discanno demonstrated his natural gift for art by painting "King Manfredi's Tournament" in 1859, a copy of a curtain made for the Piccinni Theater in Bari by the eminent Terlizzi painter, Michele De Napoli. De Napoli was a well-known painter in Neapolitan art circles and particularly talented in historical landscape paintings and portraiture. At the time, he was involved in competition for a chair in drawing at the Reale Instituto di Belle Arti, a university-level art school in Naples founded by King Charles VII of Naples in 1752. But De Napoli's candidacy was rejected by the Bourbonian-controlled commission because of his liberal ideals. Nevertheless, Michele De Napoli's prestige was undiminished, so he could introduce Geremia Discanno for admission to the Institute as a student. A few years later, during the Risorgamento Di Napoli was named to the Board of Superintendence of the National Museum and the Excavations of Antiquities by a decree of 7 December 1860, signed by Giuseppe Garibaldi himself. During Discanno's formative years, excavations in Pompeii, finally conducted with a systematic approach beginning in 1748, yielded new, widely published discoveries every day. But excavators were dismayed to observe many paintings not removed from their original site began to decay and disappear at an alarming rate. With the unification of Italy in 1860, the legal status of Pompeii changed from being a royal possession from which monarchs could use the site to obtain antiquities for their private collections or to gift artifacts to illustrious foreign guests, to property of the state. Archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli was named superintendent and he began to manage the excavations to transform Pompeii into a place to visit to gain a glimpse into the past of western civilization and begin to understand those who went before the modern world. Fiorelli developed an address system to identify each structure within the ancient city. Then he focused on copying and cataloging the frescoes left in situ. Meanwhile, Discanno studied under the guidance of conformists Domenico Morelli and Filippo Palizzi, two of the faculty who voted to expel Discanno's former neighbor, De Nittis, from the Institute for insubordination in 1863. In 1866, Discanno, the ever-diligent pupil, received a scholarship from his home province of Bari to refine his art in Florence. There, he again encountered his former neighbor, De Nittis. Discanno participated in the "Solemn Exposition of the Society of Encouragement of the Belle Arts" and garnered respectable sums for his paintings, more than acclaimed artists Giovanni Boldini, Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini.[2] Although De Nittis did not participate in that exhibition, both Discanno and De Nittis exhibited in Turin in 1867 and sold work there.[2] However, De Nittis left suddenly for Paris and the bright lights of the Ville Lumière[4] while Discanno returned south, retiring in solitude to a remote farm in the Canosan countryside. Work in Pompeii Between 1868 and 1870, Discanno shuttled back and forth between the farm and the city while he continued to paint, but struggled with stingy commissions and few awards. In 1870, a triumphant and newly married De Nittis returned to Naples flush with success from his Parisian exhibitions and salons. Discanno returns to Naples as well. There he renewed his acquaintance with Giuseppe Abbate, the elderly first draftsman of the Royal Excavations who he may have first encountered at the Florence exhibition of 1866. Abbate was a pupil, then close collaborator of Wilhelm Johann Karl Zahn since 1833. Zahn had been working with excavators in Pompeii under the direct assignment of the King of the Two Sicilies. It is thought this relationship led to Giuseppe Fiorelli's 1870 commission of Discanno to begin copying the frescoes being unearthed in Pompeii.[2] In Fiorelli's "The excavations of Pompeii from 1861 to 1872" published in 1873, more than fifty of Discanno's meticulous drawings made between 1870 and 1872 are listed.[5] In 1874, a young art historian from Leipzig, Emil Presuhn, moved to Pompeii and immediately came into contact with Discanno. Their collaboration resulted in the publication of "Die Pompejanische Wanddecoration" (The wall frescoes of Pompeii) published in Leipzig in 1877, containing 24 color plates of Discanno's faithful reproductions,[6] followed by "Pompeji: Die neuesten Ausgrabungen von 1874 bis 1878" (Pompeii: the last excavations from 1874 to 1878) containing 60 plates of Discanno's watercolors.[7] A third publication, updating and extending the previous one, "Pompeji: Die neuessten Ausgrabungen von 1874 bis 1881" containing 80 color plates of Discanno's watercolors was published in 1882 after the untimely death of Presuhn, who died at the age of only 36.[8] Sampling of work from Pompeii

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pompeii by Geremia Discanno. After Fiorelli left the excavations in 1875, Discanno was directly employed by the Superintedency in 1876. Antonio Sogliano who became director of excavations between 1905 and 1910 recalled there was the workshop of Discanno, in which Geremia with the help of some collaborators crushed and mixed paint colors to use in the reproduction of the Pompeian frescoes. Sogliano said the paintings made by "the master" were so realistic, even in the reproduction of the cracks in the wall, that more than once expert archaeologists had mistaken them for the originals.[9] Discanno became so knowledgeable about the art of Pompeii that he served as arbiter in controversial interpretations between archaeologists and art historians. He was also consulted repeatedly by renowned Dutch painter of classical subjects, (Sir) Lawrence Alma-Tadema. By 1882, Discanno began to work directly with the Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut, the German Archaeological Institute, in Rome. Based on archived drawing dates, Discanno's collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute continued until 1890.[2] In 1890, Discanno was commissioned by the empress Elizabeth Amelie Eugenie von Witterback, wife of Franz Joseph of Hapsburg, emperor of Austria-Hungary, to decorate the vaults and stairways of her imperial villa known as the Achilleion, on the Greek island of Corfu with Pompeian designs.[10] Between 1902 and 1904, Discanno was engaged in the development of an adhesive to preserve frescoes exhibited at the museum in Naples as evidenced by correspondence in the archive of the Superintendency of Naples. Curators wanted to remove protective waxes that had been applied in the middle of the 19th century which were irreparably yellowing the works.[11] Unfortunately, Discanno was sued by one of his subordinates and their collaborators, who claimed to be the actual inventor and demanded exclusivity of the process. When the trial went badly for the subordinate, the man insisted the solution was poisonous whereby Discanno dramatically seized the evidence vial of the liquid and took a sip to prove the falsity of the claim. Although Discanno won the case, his desire for confidentiality of the proceedings was not upheld. Other commissionsAs photography became more economical, fewer requests were made for Discanno to copy works at Pompeii, so he turned to private commissions to decorate churches, hotels, government chambers, such as the council chamber in Resina, opera and manner houses. He also continued to paint oils on canvas depicting Apulian rural scenes.[2] One of his most complex works at this time was the execution of the frescoes in Palazzo De Prisco in Boscoreale in 1900. There, he reproduced the Pompeian 2nd style frescoes of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor originally found in Boscoreale. The original frescoes were sold off by the landowner to the Louvre, the Musée Royal de Mariemont in Mariemont, Belgium and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as private collectors,[12] an act that outraged members of Italian parliament including archaeologist Felice Barnabei, a disciple of Pompeian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli.[13] Although the sale of the Boscoreale frescoes was not prevented, in 1902 Italian Parliament approved the first regulation for the protection of Italy's cultural heritage.[14] His work in Boscoreale is thought to have been Discanno's last commission. Discanno died shortly after its completion on January 14, 1907, in Naples. The Bulletin of Art published by the Directorate General of Antiquities and Fine Arts published his obituary expressing their appreciation for the precious artistic work he carried out in the service of archeology and in particular the excavations of Pompeii.[15] The Municipal Administration of Barletta named a city street after him. But, his last effort in Boscoreale now lies within an abandoned and neglected building, as forgotten as he has become.[2] Notes

Other biographical referencesBOERMANN KARL, Kunstchronik: Wochenschriftfür Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, n o 41 - Leipzig, July 19, 1877 CHRISTOMANOS CONSTANTIN, "Elizabeth of Austria in Constantin Christomanos' diary sheets" edited by Verena von der Heyden-Rynsch, translation by Maria Gregorio - Adelphi Edizioni SpA - Milan, 1989 COMANDUCCI AM, "Italian painters of the 19th century" - Milan, 1934 DELPINO FILIPPO, "Felice Barnabei and art and antiquarian collecting in Ghia tofilo mas. Written in memory of Gaetano Messineo" by E. Mangani, A. Pellegrino, Edizioni Espera - Rome, 2016 DE NITTIS GIUSEPPE, "Notes et souvenirs du peintre Joseph De Nittis" Ancienne Maison Quantin - librairies imprimeries reunies - Paris, 1895 DE TOMASI FRANCESCA, "Diplomacy and archeology in late 19th century Rome", in "Horti Hesper idum - Studies in the history of collecting and artistic historiography" - Rome, 2013 DORONZO GIUSEPPE, "Ancient villages of Barletta - vol. 1 - 11 territory outside the walls" by CRSEC Regional Center for Educational Cultural Services - Bari, 2003 FARESE SPERKEN CHRISTINE, "19th century painting in Puglia" - Mario Adda Editore - Bari, 1996 FIORELLI GIUSEPPE, "The excavations of Pompeii from 1861 to 1872", Italian typography of the Liceo V. Emanuele - Naples, 1873 "Description of Pompeii", Italian typography of the Liceo V. Emanuele ImageNapoli, 1875 FURCHHEIM FRIEDRICH, "Bibliography of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabia" ImageNaples, 1891 GIONTA DANIELE, "Pastures and antiques - correspondence with Felice Barnabei (1895-1912)", - 2014 GAEDESCHENS, RUDOLF, "Unedirte antike Bildwerke", Jena, 1873, courtesy Universitatsbibliothek Heidelberg HERON DE VILLEFOSSE ANTOINE, "L'argenterie et les bijoux d'or du Trésor de Boscoreale", Ernst Leroux Editeur, Paris, 1903 IASIELLO ITALO, "Naples from capital to suburbs - Archeology and antiques market in Campaniq in the second half of the 19th century", Federico II University Press - Naples, 2017 MARTORANA PIETRO, "Biographical and bibliographic information of the writers of the Neapolitan dialect", Chiurazzi Editore, Naples, 1874 MAU AUGUST, "Geschichte der decorativen Wandmalerei in Pompeji, Printing and publishing ( edited by) G. Reimeer, Berlin, 1882 MIRAGLIA, MARINA AND OSANNA MASSIMO, "Pompeii, photography", Electaphoto, Verona, 2015 NECCO LUIGI, "The mystery of Troy. In search of the treasure by Schliemann" Tullio Pironti Editore - Naples, 1993 NICCOLINI FAUSTO E FELICE, "The houses and monuments of Pompeii drawn and described", Naples, 1896 OSANNA MASSIMO, "Pompeii the rediscovered time", Rizzoli - Milan, 2019 PASQUI ANTONIO, "The Pompeian villa of Pisanella", in "Ancient monuments published by the Royal Academy of the Lincei", U. Hoepli - Milan, 1897 RUGGERO MICHELE AND OTHERS, "Pompeii and the 1st region buried by Vesuvius in 79 AD", printing establishment of Cav. F. Giannini ImageNaples, 1879 SCHARF GEORGE JR., "The Pompeian Court in the Crystal Palace", Crystal Palace Library - London, 1854 SIOTTO ELIANA, 'Wall pictures from Vesuvian sites: the question of paints in the second half of the nineteenth century", in "Rivista di studi Pompeiani - XV", L'erma di Breitschneider - Pompei, 2004 SOGLIANO ANTONIO, "The Archaeological School of Pompeii", Regia Accademia dei Lincei - Rome, 1940, in "Various writings" pag. 338 et seq. SZTÀRAY IRMA, "Elisabeth the last years", A. Holzausen - Vienna, 1909 VERBANCK-PIÉRARD ANNIE, "La villa romaine de Publius Fannius Synistor à Boscoreale" - Morlanwelz (BE), 2010 VISTA FRANCESCO SAVERIO, "Barletta before and after 1860", Stab. Typographic G. Dellisanti - Barletta, 1899 "Fondo FS Vista" documentary collection at the De Gemmis Library in Bari, containing autographed notes of historical research never published. ZECCATO, NUNZIO, "November 11, 1890. Princess Sissi visits Naples and falls in love with it ", Vesuviolive website - Naples, 11 Nov 2018 |

||||||||||||||