|

George Kephart

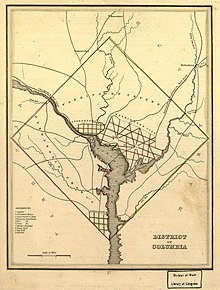

George Kephart (February 7, 1811 – August 26, 1888) was a 19th-century American slave trader, land owner, farmer, and philanthropist. A native of Maryland, he was an agent of the interstate trading firm Franklin & Armfield early in his career, and later occupied, owned, and finally leased out that company's infamous slave jail in Alexandria (originally District of Columbia, after March 13, 1847, Alexandria, Virginia). In 1862, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts mentioned Kephart by name in a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate as one of the traders who had "polluted the capital of the nation with this brutalizing traffic" of selling people. BiographyEarly life and family Kephart was born in what was then Frederick County, Maryland (later Carroll County), most likely on his parents' farm, which was then known was Brick Mills, and was renamed Trevanion by a subsequent owner.[1][2] Brick Mills was named for its large brick gristmill that used Big Pipe Creek for water power.[3] Other outbuildings constructed in the Kephart era included a still house built by David Kephart II, George Kephart's father.[1] George Kephart had a number of siblings who survived to adulthood, including Philip Kephart, who became a doctor and settled in Berrien Springs, Michigan,[4] and Peter Kephart, who engineered and marketed home refrigeration appliances.[5] On his mother's side, Kephart was a Reister,[4] and he lived out his later life in Reistertown, Baltimore, which was founded by an ancestor.[6] The family were of the Lutheran Protestant faith and Kephart's parents and grandfather were buried in the community's Lutheran cemetery.[7] Kephart inherited Brick Mills after his father's death in 1836.[1] Slave trading (c. 1827–1852)    Kephart may have been trading as early as 1827, when he was just 16, buying locally and selling in New Orleans and Natchez, Mississippi.[8] Historian Frederic Bancroft introduced Kephart in Slave-Trading in the Old South with the description "Early in the 'thirties a small trader, living near a little ferry on the upper Potomac, was searching for slaves throughout Montgomery and Frederick counties, Maryland. He knew all the country roads, the names and the financial condition of most of the slaveholders. He was regularly at certain taverns and stores in Fredericktown and Bockville to get letters from or to meet persons that had been attracted by reports of his liberal offers. And he promptly inspected all proffered slaves."[9] Per the Negro History Bulletin, Kephart and his regional compatriots were the right men at the right place at the right time for the job the abolitionists called soul-driving: "Because Alexandria was the best point from which to start both coast-wise shipments and overland coffles, large numbers of slaves passed through Washington from Maryland to Alexandria. In 1827 Benjamin Lundy wrote: 'It is my decided opinion that were we to search the globe from Kamchatka to the southern pole, we could not find a people more tyrannical, more completely lost to feelings of humanity and justice, than the heartless wretches who carry on the United States slave trade through Maryland and the District of Columbia.'"[10] There is reason to believe that Kephart had one or more slave prisons on his own Maryland farm:[a]

Circa 1834 Kephart was hired on as one of five agents (along with Rice C. Ballard, James F. Purvis, Jourdan Saunders, and Thomas M. Jones) who worked full-time collecting enslaved people from throughout the greater Chesapeake region for Franklin & Armfield to ship south.[14] After Franklin and Armfield sold out of the slave trade in the mid-1830s, Kephart built on their existing business network as well as expanding in new directions, allying with traders including Purvis and his brother Isaac F. Purvis, Hope Hull Slatter, Bacon Tait, Thomas Boudar, Sidnum Grady, and James H. Birch.[15] Between 1837 and 1846 he leased, and between March 12, 1846, and 1859 he owned, the Alexandria, Virginia slave pen originally used by Franklin & Armfield that is now known as the Freedom House Museum, located at 1315 Duke Street. In the early 1840s he seems to have been in a legal partnership with Tait of Richmond and Boudar of New Orleans.[16] Observers and visitors to the prison typically found about 50 people imprisoned there, but one source claims there was capacity for up to 300 enslaved people. In 1841, a visitor was informed that Kephart annually shipped 1,500 to 2,000 people south.[17] According to the author of The Ledger and the Chain (2021), these numbers are likely exaggerated.[15] Kephart was most likely operating the 1315 Duke Street slave jail at the time Dorcas Allen killed her children there in 1837.[18][19] Similarly, Kephart's jail was used as a transfer point for people trafficked in the 1838 Jesuit slave sale, such as a man named Charles Queen, and a woman named Anny and her children Arnold and Louisa.[20] Charles Queen was shipped south on the Isaac Franklin, a brig that Kephart had purchased from Franklin and Armfield.[20] In 1846 Kephart and Virginia-based trader Joseph Bruin went to chancery court against each other in Fairfax County, Virginia; the case file mentions over 100 different enslaved people.[21] In 1847, the section of the District of Columbia that was south of the Potomac River was retroceded to Virginia; the Compromise of 1850 abolished the slave trade in the District, but Kephart and his agents and clients would have been unbothered by these changes—it was a short trip over the river and back for anyone who wished to buy or sell slaves.[22] In 1851 the abolitionist William Goodell wrote that the slave trade's "general prosecution may be seen by the numerous advertisements of both purchasers and venders, in the most respectable newspapers in the slave states" and included an undated Kephart ad from the Alexandria Gazette seeking to acquire "likely Negroes, from 10 to 25 years of age".[23] Also in 1851, The Liberator surmised that Kephart mentioned in a letter about taking advantage of the Fugitive Slave Act to enrich their "inventory" was the same man who was involved in the attempted recapture of fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins; however, The Liberator was incorrect—the slave catcher in the Minkins case was one John Caphart of Norfolk, Virginia.[24] Kephart claimed to have quit slave trading in June 1852.[25] However, he remained owner of the slave pen, renting it to other slave traders.[26] He was also an investor or silent partner in the successor business, Price, Birch & Co. for the first year (c. 1858–59) it was operating at Duke Street.[27] Kephart sold the building in 1859, it was operated as a slave jail by Price & Cook for a time, and finally it was captured and liberated by the U.S. Army on or around May 24, 1861.[28]   In the 1920s, a local historian named William Jarboe Grove, whose parents had socialized with the Kepharts, rationalized George Kephart's slave-trading career with period-typical patriarchal canards: "Mr. Kephart although a slave dealer was a man with a kind heart and treated his slaves well, as long as they were in his hands, and they would conduct themselves properly as it was also to his interest to take good care of them as they were valuable property and he could not afford to mistreat them."[13] On other hand, Fred Fowler, who was born enslaved in Frederick County, Maryland, escaped with assistance from the Underground Railroad, served in the U.S. Colored Troops, and who was employed at the Library of Congress from 1876 to 1919,[30] told Frederic Bancroft, "Ever'body in Frederick knowed Kephart, an' was afeerd of 'im, too. When it was reported that he was about, they trembled. At different times, two years apart, he bought my uncle Lloyd Stewart and my aunt Margaret Stewart. He was supposed to have sent 'em to Georgia, but they was nevah heerd from."[31] American Civil War and later lifeIn 1860, George Kephart or someone in Baltimore with the same name was arrested for assaulting a black man: "George Kephart was yesterday arrested by policeman McCullough for disorderly conduct and committing an assault on Richard Dorsey, colored. The difficulty arose about a wagon, belonging to the colored man, standing in the street, which the accused wanted to pass."[32] In 1862 U.S. Senator Henry Wilson denounced Kephart as a key slave trader of the District of Columbia in a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate:[33]

Moncure Daniel Conway's Testimonies Concerning Slavery devoted a chapter called "The Slave Harvest — Mysteries of a Shamble" to George Kephart and his jail. Per Conway, "Ever since I can remember, the chief slave-dealing firm in [Virginia], and perhaps any where along the border between the Free and Slave States. Every slave that tries to escape to a Free State was invariably sold if caught, and generally lodged in Kephart's shamble, and never suffered to return to the place from which he ran, lest he should tell others the means of his escape." The bulk of the chapter is devoted to quoting from letters removed from the jail when it was captured by U.S. troops at the beginning of the American Civil War. One elderly man was left behind; per Conway the shackles that bound him were removed and sent to Henry Ward Beecher as a sort of memento of the success of the abolition movement in the United States. The captured letters dated from 1837 to 1857 and included correspondence from a number of affiliates including the usual suspects, Brashear of Natchez[c], one Mr. Sims,[d] and others.[38]  In 1867 George Kephart donated "½ acre of land to the Methodist Episcopal Church of Baltimore County to erect a school house for colored children and a cemetery to bury the dead. This school in 1872 became part of the Black Public School System of Baltimore County and was designated Reisterstown School for Colored Children number 22."[39][unreliable source?] At the time of the 1870 and 1880 censuses, Kephart was living in Baltimore, sharing a household with his widowed sisters, who kept house, and his nieces.[40][41] Kephart died in 1888 after multiple strokes. He had been living with his sister and was described in an obituary as a "bachelor of sociable tastes".[42][43] In his obituary he was described as having been a prosperous farmer, there was no mention of his past career as a slave trader.[42][43] LegacyThe American poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier visited three slave jails in the District of Columbia in 1841, including the one at 1315 Duke Street.[44] He later wrote a poem called "At Washington" that was subtitled "Lines, Suggested by a visit to the City of Washington, in the 12th month of 1845",[45] and which historians suggest may have influenced by his visit to the slave jail owned at that time by Kephart.[44]

Four documents from Kephart's slave-trading business, including the bill of sale for an enslaved woman, are in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society.[46] In 2021, the Kephart Bridge Landing in Loudoun County, Virginia, was nominated for renaming, as the existing name commemorated a major slave trader.[47] Kephart "owned land along Goose Creek crucial to his business of transporting the enslaved from port to port."[48] In 2022 the landing was renamed Riverpoint Drive Trailhead.[48] See also

Explanatory notes

ReferencesCitations

Sources

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||