|

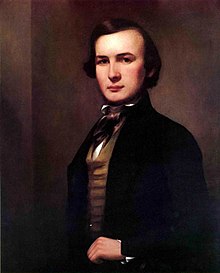

George Henry Durrie George Henry Durrie (June 6, 1820 – October 15, 1863) was an American landscape artist noted especially for his rural winter snow scenes, which became very popular after they were reproduced as lithographic prints by Currier and Ives. Early lifeDurrie was born in New Haven, Connecticut, one of six children born to John and Clarissa Clark Durrie, who were Hartford natives. The Durries moved to New Haven in 1818, where John Durrie became a partner in the printing firm of Durrie and Peck, stationers and book publishers.[2] In 1837 John Durrie contracted with Nathaniel Jocelyn, a noted New Haven engraver and portrait painter, for painting instruction for George Durrie and his brother John.[3] By 1839, George Durrie was painting portraits professionally in Hartford and Bethany, Connecticut, and in 1840, he was working in Meriden and Naugatuck, Connecticut.[4] Marriage and childrenDurrie was a very religious person who usually attended two or more church services each Sunday. He also liked to sing, and played the viol.[5] While he was working in Bethany, he stayed with the Wheeler family, and attended services at Christ Episcopal Church, where he became friends with the choir-master, Archibald Abner Perkins. A frequent dinner guest at the Perkins home, Durrie fell in love with Sarah Perkins, Archibald’s daughter, who was a school teacher in Hartford at that time. They married on September 14, 1841, and lived on Elm Street in New Haven. The Durries had three children, George Boice Durrie, born in 1842; Benjamin Woodhouse Durrie, born in 1847; and Mary Clarissa Durrie, born in 1852.[6] Professional lifeFor many years, Durrie made a living primarily as a portrait painter, executing hundreds of commissions. After marriage, he made frequent trips, traveling to New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Virginia, fulfilling commissions and looking for new ones. His diary reveals that he was an enthusiastic railroad traveler, in the early days of the railroads.[7] Durrie also painted what he called "fancy pieces", whimsical studies of still lives or stage actors, as well as painting scenes on window-shades and fireplace covers.[8] But portrait painting commissions became scarcer when photography came on the scene, offering a cheaper alternative to painted portraits, and, as his account-book shows, Durrie rarely painted a portrait after 1851.[9] Durrie’s interest shifted to landscape painting, and while on the road, or at home, made frequent sketches of landscape elements that caught his eye. Around 1844 Durrie began painting water and snow scenes, and took a second place medal at the 1845 New Haven State Fair for two winter landscapes.[10] Although he had some training in portrait work, Durrie was self-taught as a landscape artist. He was undoubtedly influenced both by the American Hudson River School, and also by European artists, by studying exhibitions of their work at the New Haven Statehouse, the Trumbull Gallery, and at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, as well as in New York City. Durrie himself exhibited regularly, both locally, and in New York City at the National Academy of Design and the American Artists’ Union, and his reputation grew. Durrie was especially known for his snow pieces, and would often make copies or near-copies of his most popular pieces, with modifications to order.[11] The landscapes painted by Durrie offered a more intimate view than the panoramic landscapes painted by the Hudson River School, which was the leading school of American landscape painting. Colin Simkin notes that Durrie’s paintings took in a wide angle, but still "close enough to be within hailing distance" of the people who are always included in his scenes.[12] Currier and IvesDurrie’s early landscapes were often of local landmarks, such as East Rock and West Rock, and other local scenes, which were popular with his New Haven clients, and he painted numerous variations of popular subjects. As his portrait commissions declined, Durie concentrated on landscapes. He wanted a wider audience, and he seemed to have a good sense of what would sell. Durrie realized that his paintings would have a wider appeal if he made them as generic New England scenes rather than as identifiable local scenes, retaining, as Sackett said, "a sense of place without specifying where that place was".[13] The New York City lithographic firm of Currier & Ives knew their audience; the American public wanted nostalgic scenes of rural life, images of the good old days, and Durrie’s New England scenes fit the bill perfectly. Lithographic prints were a very democratic form of art, cheap enough that the humblest home could afford some art to hang on the wall. Durrie had been marketing his paintings in New York City, and Currier and Ives, who had popularized such prints, purchased some of Durrie’s paintings in the late 1850s or early 1860s, and eventually published ten of Durrie’s pictures beginning in 1861. Four prints were published between 1861 and the artist's death in New Haven in 1863; six additional prints were issued posthumously.[14] Home to Thanksgiving, one of Durrie’s snow scenes, became one of Currier and Ives’ most popular prints, and is still being reproduced at holiday times. The popularity of Durrie’s snow scenes received an additional boost in the 1930s, when the Traveler’s Insurance Company began issuing calendars featuring Currier and Ives prints. Starting in 1946, the January calendar always featured a Durrie snow scene.[15] Historian Bernard Mergen notes that "84 of the 125 paintings attributed to him are snowscapes, more than enough to make him the most prolific snow scene painter of his time."[16] LegacyIn Durrie’s time, winter landscapes were not popular with most curators and critics, but nevertheless, by the time of his death, Durrie had acquired a national reputation as a snowscape painter. Durrie died in 1863, at age 43, probably from typhoid fever, not long after Currier and Ives began reproducing his paintings as prints.[17] Durrie’s paintings, depicting idyllic rural life, a world of stability and home comforts, held great appeal for the middle class and the working class, as an visual antidote for the growing industrialization of America, and the uncertainties of a boom-and-bust economy. The American ideal of a land of self-sufficient farmers, captured by Durrie’s paintings, was being replaced with factories belching smoke, along with a rise in urban populations, foreign immigration, and crime brought about by crowded conditions and poverty. The American descendants of the early English settlers felt that their values and way of life were threatened by these new developments, and turned to nostalgic images such as Durrie’s for comfort.  Durrie was dismissed by critics as a popular artist, an illustrator rather than a fine artist. Although Durrie’s Currier and Ives prints were popular, his name was still relatively unknown. But a revival of interest in Durrie began in the 1920s with the publication in 1929 of Currier and Ives, Printmakers to the American People, by collector Harry T. Peters, Sr., who called Durrie’s prints "among the most valued In the entire gallery [of Currier and Ives prints]", and says that Durrie was known as the "snowman" of the group.[18] Peters called Durrie’s Home to Thanksgiving "perhaps the most widely known Currier and Ives print in this country today."[19] Peters’ book, and the Traveler’s calendars, spurred new interest in Durrie, and his work was re-evaluated by the critics. Durrie’s work was included in an exhibit entitled Hudson River School and the Early American Landscape Tradition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1945, followed by a one-man show of Durrie’s work at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford in 1947. More one-man shows followed, at the Dayton Art Institute in 1951, New Jersey Historical Society in 1959, the New Haven Colony Historical Society in 1966, and at the Lyman-Allyn Museum in 1968.[20]  In the estimation of art historian Martha Young Hutson, Durrie’s "lack of academic training permitted him to develop an idiomatic style that was peculiarly suited to his theme. Instead of being absorbed by the Hudson River School, he … develop[ed] a means of expression uniquely his own … he is neither in the academic camp nor among the amateurs." Art historian Wolfgang Born characterized Durrie’s work as "fresh, genuine, and thus convincing—qualities too often missing in the art of then-famous artists."[21] While Durrie’s name is still relatively unknown, collector interest continues to grow; in 2018 his painting Hunter in a Winter Wood sold at auction for $312,500.00.[22] Collections holding paintings by Durrie include the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, ME; the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne VT; the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; the White House in Washington, D. C.;[23] the New Haven Museum, New Haven, CT; the Lyman-Allyn Museum, New London, CT; the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, CT; the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, CT; and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT. GalleryWikimedia Commons has media related to George Henry Durrie.

Notes

References

|