|

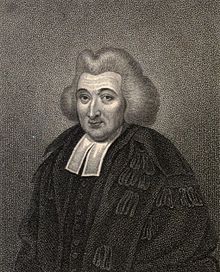

George Campbell (minister)

George Campbell FRSE (25 December 1719 – 6 April 1796) was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, minister, and professor of divinity. Campbell was primarily interested in rhetoric, since he believed that its study would enable his students to become better preachers. He became a philosopher of rhetoric because he took it that the philosophical changes of the Age of Enlightenment would have implications for rhetoric. Life, times, and influencesCampbell was born on 25 December 1719 in Aberdeen the son of Colin Campbell (1678-1728) minister of the Kirk of St Nicholas in Aberdeen, and of Margaret Walker, daughter of Alexander Walker, an Aberdeen merchant.[1] At the age of fifteen, Campbell attended Marischal College where he studied logic, metaphysics, pneumatology (philosophy of mind and/or spirit), ethics, and natural philosophy. After graduating with his M.A. in 1738, Campbell decided to study law and served as an apprentice to a writer to the Signet in Edinburgh. He began gravitating towards theology after attending lectures at the University of Edinburgh. After serving out his term as an apprentice, he returned to Aberdeen and enrolled at both King's and Marischal Colleges, University of Aberdeen as a student of divinity. Because of the tumultuous political landscape in Scotland, Campbell's divinity examinations were delayed until 1746 when he received his licence to preach. Within two years, he received ordination at the parish of Banchory Ternan. The origin of Campbell's scholarly career can be traced back to his years at the parish. He established himself as a scripture critic, and lecturer of holy writ. Campbell began his lifelong ambition of translating the gospels, and around 1750, he composed the first two chapters of The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Campbell's growing reputation impressed the magistrates of the city of Aberdeen and he was offered a ministerial position in 1757. His return brought him to the core of the growing intellectual community in northeast Scotland. In 1759, Campbell was offered the position of principal at Marischal College and he fully immersed himself in university affairs. During his time at Marischal, Campbell was a founding member of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society along with philosopher Thomas Reid, John Gregory (mediciner), David Skene, John Stewart and Robert Trail. Many members of the Society, including Reid, Campbell, and Gregory, were great admirers of Francis Bacon, so the group's aim directed toward the exploration of the sciences of the mind. The Aberdeen Philosophical Society is most often remembered for its philosophical publications, notably: Reid's Inquiry into the Human mind, on the Principles of Common Sense (1764), James Beattie's Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth (1770), and Alexander Gerard' Essay on Genius. Campbell's work was very much influenced by the group's members. The Philosophy of Rhetoric was originally read in discourses before this Society. Campbell's emphasis on the trustworthiness of the senses and his exploration of tendencies basic to human nature have been attributed to the influence of his colleague in the society, the common sense philosopher, Thomas Reid. Campbell's first major publication, A Dissertation in Miracles (1762), was directed against David Hume's attack on miracles in An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding. Campbell was influenced by Hume, but took particular issue with his philosophical strictures. Even though both were in complete opposition over almost every point of philosophy, Campbell and Hume shared a mutual respect. Thanks in part to the success of Miracles, Campbell became a professor of divinity at Marischal in 1770. He lectured to students to prepare them for the demands of the ministry, both practical and spiritual. Campbell gave lectures on Church history, later published as Lectures on Ecclesiastical History, and on pastoral character and preaching, later published as Lectures on Pulpit Eloquence. After completing The Philosophy of Rhetoric (1776), Campbell published several sermons and finished his lifelong ambition, The Four Gospels, Translated from the Greek (1789). In December 1793 he was a founder member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[2] Campbell continued lecturing until ill health forced him into retirement in 1795 and he died on 6 April 1796. He is buried in St Nicholas Churchyard in Aberdeen under a table stone. Campbell's Theory of Moral Reasoning Campbell ascertained that the human mind is separated into various faculties that serve the purpose of dictating moral reasoning. To his reasoning moral reasoning was a hierarchal system initiated by individual understanding of a given situation and moves on through imagination and personal desire. Campbell was clear that there were seven circumstances involved in a person's decision to act on their impulses as described by The Rhetoric of Western Thought. The first is probability, the second is plausibility, the third is importance, the fourth is proximity of time, the fifth is connection, the sixth is relation, and the last is interest in the consequences. All of which play a major role in the manner in which a person operates. LegacyCampbell as an enlightened thinkerWhile Campbell's literary life was dominated by pedagogical and pastoral concerns, it is apparent that his mind was tempered by the values of the Enlightenment. Campbell believed that the Enlightenment was the ally to a moderate, rational, and practical Christianity, rather than a threat. His faith required that his religious evidences to be complete while his enlightened thinking required faith to give it purpose. Throughout Campbell's literary career, he focused on enlightened concerns such as rhetoric, taste, and genius—perhaps a result of his time in the Aberdeen Philosophical Society. His attempt to align rhetoric within the sphere of psychology resulted from Francis Bacon's survey of the structure and purpose of knowledge. The Philosophy of Rhetoric illustrates the Baconian influence of inductive methodology but also scientific investigation—two major concerns of the Enlightenment. As well, Campbell's appeal to natural evidences was a similarity in process shared by most of the great minds of the Enlightenment. This is seen throughout his writing, with particular emphasis on placing methodology before doctrine, critical inquiry before judgment, and his application of tolerance, moderation, and improvement. Campbell and faculty psychologyCampbell embraced the philosophical empiricism which John Locke established in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Following the example of Locke's humanistic sciences, Campbell set forth an analysis of rhetoric through the scope of mental faculties. He believed that a rhetoric grounded in empiricism would become efficient because of the incorporation of the cognitive processes. The human senses are the basis for the validity of belief; thus a rhetorical theory based in faculty psychology would establish that rhetoric is capable of making a reader experience a concept with the same "vivacity" and automaticity as that of the senses. Campbell, like most theorists of the Enlightenment, believed in a universal human nature: the "general principles [of taste] are the same in every people".[3] He gives the example of tropes and figuration which "are so far from being the inventions of art, that, on the contrary, they result from the original and essential principles of the human mind".[4] This facet of human nature has remained constant throughout history so it must be universal trait. Based on premises similar to this, Campbell claimed that human beings act according to clear and obvious motives and rhetoric should be, in turn, directed towards similar operations of the mind. To persuade effectively, Campbell believed that the orator should adapt his or her discourse to the needs of the audience, for as he states: "whatever be the ultimate intention of the orator, to inform, to convince, to please, to move, or to persuade, still he must speak so as to be understood, or he speaks to no purpose".[5] He classifies the needs of the audience into four different categories:

The purpose of discourse is derived from the powers of the mind to which they appeal (understanding, imagination, passions, will), rather than the classical three, which are based on the public purpose of oration. The classical categories (see Cicero and Quintilian) are the demonstrative, to praise or blame; the deliberative, to advise or dissuade; and the forensic, to accuse or defend. In considering each of these, Campbell believes that not only understanding and memory of the audience must be taken into account, but the orator must as well provide particular attention at stimulating their passions. To incorporate this was as an obvious concern for Campbell, who believed that effective preaching must be measured by its effects on the audience. Campbell and evidenceTo move an audience, Campbell believed that a rhetorician must appreciate the relationship between evidence and human nature. Campbell divided evidence into two major types: intuitive and deductive. Intuitive evidence is convincing by its mere appearance. Its effect on the power of judgment is "natural, original, and unaccountable",[6] which suggests that no other additional evidences can make it more compelling or effective. Campbell subdivides intuitive evidence into three sources: abstraction, consciousness, and common sense. These are responsible for our understanding of metaphysical, physical, and moral truths. Deductive evidence, unlike intuitive, is not immediately perceived. It must be demonstrated either logically or factually since it is not derived by premises but with comparing ideas. Deductive evidence originates from one of two sources: demonstrative or moral. Demonstrative concerns itself with abstract and invariable relations of ideas; moral, on the other hand, is concerned only with matters of fact. Campbell had the idea of both moral and scientific reasoning. In his book, The Philosophy of Rhetoric, the philosopher states four types of evidence that goes into reasoning. The first one is that reasoning comes from experience and how past experiences shape our sense of reason for present, and future reasoning. The second type of evidence is analogy, to analyze a situation we are able to get more of an understanding and view what needs to be done in the future to better an outcome. The third type of evidence is testimony. Testimony has to deal with written or oral communication. The very last is calculations of chances. Knowing that chance is not predictable a person can assume and use reason when it comes to other certain types of happenings. Campbell's critique of AristotleCampbell believed that Aristotle's syllogistic method is faulty for four reasons:

Campbell and HumeIn David Hume's essay, Of Miracles, he assesses the credibility of testimony for miracles, and claims that our acceptance of it is based on experience; thus when testimony goes against the evidence of experience, it is a likely reason to reject the testimony. In response, Campbell published A Dissertation on Miracles to refute Hume's essay. He believed that Hume misrepresented the importance of testimony in attaining knowledge. Our faith in the representation of others is an original component in human nature. As proof, Campbell provides the example of children who readily accept the testimony of others. It is not until they get older and become sceptical that testimony is rejected; proof that our trust in witnesses precedes that of experience. For Campbell, the belief of testimony is part of human nature, since it is an unlearned and automatic response. Testimony is thus closer to evidence from consciousness than that from experience. Campbell argues that the most important factor in determining the authenticity of testimony is the number of witnesses. Numerous witnesses and no evidence of collusion will supersede all other factors, since the likelihood of testimony outweighs that of Hume's formula for determining the balance of probabilities. According to Campbell, Hume is wrong to claim that testimony is a weakened type of evidence; it is capable of providing absolute certainty even with the most miraculous event. WorksWriting

Sermons and lecturesCampbell's sermons and lectures provide important insights into the structure of his thought and range of his scholarly activities.

Quotations

References

Notes

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||