|

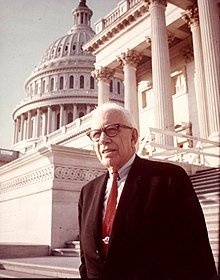

George Aiken

George David Aiken (August 20, 1892 – November 19, 1984) was an American politician and horticulturist. A member of the Republican Party, he was the 64th governor of Vermont (1937–1941) before serving in the United States Senate for 34 years, from 1941 to 1975. At the time of his retirement, he was the most senior member of the Senate, a feat which would be repeated by his immediate successor Patrick Leahy. As governor, Aiken battled the New Deal over its programs for hydroelectric power and flood control in Vermont.[1] As a Northeastern Republican in the Senate, he was one of four Republican cosponsors of the Full Employment Act of 1946. Aiken sponsored the food allotment bill of 1945, which was a forerunner of the food stamp program. He promoted federal aid to education and sought to establish a minimum wage of 65 cents in 1947. Aiken was an isolationist in 1941 but supported the Truman Doctrine in 1947 and the Marshall Plan in 1948. In the 1960s and 1970s, he steered a middle course on the Vietnam War, opposing Lyndon Johnson's escalation and supporting Richard Nixon's slow withdrawal policies. Aiken was a strong supporter of the small farmer. As acting chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee in 1947, he opposed high rigid price supports. He had to compromise, however, and the Hope-Aiken Act of 1948 introduced a sliding scale of price supports. In 1950, Aiken was one of seven Republican senators who denounced in writing the tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy, warning against those who sought "victory through the selfish political exploitation of fear, bigotry, ignorance and intolerance."[2] Early lifeGeorge David Aiken was born in Dummerston, Vermont, to Edward Webster and Myra (née Cook) Aiken.[3] In 1893, he and his parents moved to Putney, where his parents grew fruits and vegetables and his father served in local offices including school board member, select board member, and member of the Vermont House of Representatives.[4] Aiken received his early education in the public schools of Putney, and graduated from Brattleboro High School in 1909.[5] Aiken developed a strong interest in agriculture at an early age, and became a member of the Putney branch of the Grange in 1906.[6] In 1912, he borrowed $100 to plant a patch of raspberries; within five years, his plantings grew to five hundred acres and included a nursery.[3] From 1913 to 1917, Aiken grew small fruits in Putney with George M. Darrow as "Darrow & Aiken." In 1926, Aiken became engaged in the commercial cultivation of wildflowers.[7] He published Pioneering With Wildflowers in 1933 and Pioneering With Fruits and Berries in 1936.[7] He also served as president of the Vermont Horticultural Society (1917–1918) and of the Windham County Farm Bureau (1935–1936).[6] In 1914, Aiken married Beatrice Howard, to whom he remained married until her death in 1966.[8][9] The couple had three daughters, Dorothy Howard, Marjorie Evelyn (who married Harry Cleverly), and Barbara Marion; and one son, Howard Russell.[7] In 1967 Aiken married his longtime administrative assistant, Lola Pierotti.[8] Lola Aiken remained active in Republican politics until her death in 2014 at age 102.[10][11] Early political careerAiken served as a school board member in Putney from 1920 to 1937.[12] A Republican, he unsuccessfully ran for the Vermont House of Representatives in 1922.[6] In 1930, he ran successfully. He was reelected in 1932 and served from 1931 to 1935.[12] As a state representative, he became known for his opposition to private power companies over the issue of dam construction.[8] Aiken was elected as Speaker of the House in 1933, over the opposition of the Republican establishment.[7] As Speaker, he shepherded the passage of the Poor Debtor Law, which protected people who could not pay their obligations during the Great Depression.[7] In 1934, Aiken won election as Lieutenant Governor of Vermont.[12] During his 1935 to 1937 term, Democrats had achieved more representation in the Vermont Senate than they had previously, though with only seven senators as compared to 23 Republicans, they were still heavily in the minority.[13] Aiken used his position on the senate's Committee on Committees — the lieutenant governor, President pro tempore of the Vermont Senate, and a senator elected by the rest of the body — to ensure that Democrats were fairly represented on the senate's committees.[13] As a result of Aiken's initiative, Democrats were represented on almost every committee, and constituted a majority on two.[13] In addition, Aiken ensured that Elsie C. Smith, the state senate's only female member, was fairly considered with respect to committee assignments; in fact, Senator Smith was appointed to more committees than any of her peers.[13] Governor of VermontIn 1936, Aiken won election as governor, serving from 1937 to 1941.[6] Aiken earned a reputation as a moderate to liberal Republican, supporting many aspects of the New Deal, but opposing its flood control and land policies.[8] In his second term the governor launched attacks on electric utility companies, and sponsored a bill that made the Public Service Commission independent of the utilities for technical advice. To continue the effort to form a consumer-oriented PSC, he named the former head of the Vermont Farm Bureau as its chairman.[14] When only Vermont and Maine voted Republican in the 1936 presidential election, Aiken thought he was in a good position to exert national leadership in the GOP. He issued manifestos calling for a more liberal approach and sought national support. He wrote an open letter to the Republican National Committee in 1937 criticizing the party and claimed Abraham Lincoln "would be ashamed of his party's leadership today" during a 1938 Lincoln Day address.[6] During the 1940 presidential campaign, however, conservative Republicans favored Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, liberals were behind New York County District Attorney Thomas Dewey, and the media was enthusiastic for Wall Street tycoon Wendell Willkie, so Aiken's nascent campaign went nowhere.[15] During his administration, Aiken reduced the state's debt, instituted a "pay-as-you-go" road-building program, and convinced the federal government to abandon its plan to control the Connecticut River Valley flood reduction projects.[6] He also broke the monopolies of many major industries, including banks, railroads, marble companies, and granite companies.[3] He also encouraged suffering farmers in rural Vermont to form co-ops to market their crops and get access to electricity. He portrayed himself in populist terms as the defender of farmers and "common folk" against the Proctor family and other members of the conservative Republican establishment, and with Ernest W. Gibson and Ernest W. Gibson Jr. became recognized as a leader of Vermont's progressive Republicans, which came to be known as the party's Aiken-Gibson Wing. Aiken was also an opponent of the policies of Vermont's large utilities and railroads; when Aiken ran for the U.S. Senate in 1940, the pro-business wing of the party endorsed Ralph Flanders. Aiken defeated Flanders in the GOP Senate primary in 1940 and was easily elected that fall to complete the remainder of Gibson's term. He served until 1975, and was always reelected by large majorities.[16][17] U.S. Senate Senator Ernest Willard Gibson died on June 20, 1940; on June 24, 1940, Aiken appointed Ernest W. Gibson Jr. to fill the vacancy pending a special election for the four years remaining on the senior Gibson's term. The younger Gibson served as a caretaker Senator until January 3, 1941, but did not run in the election to fill the vacancy. He was succeeded by Aiken, who won the special election. Political observers assumed that the younger Gibson accepted the temporary appointment to facilitate Aiken's election; knowing that Aiken desired to become a senator, he accepted the appointment and agreed not to run in a primary against Aiken, which another appointee might have done. Ernest Gibson Jr. was willing to fill the vacancy temporarily and then defer to Aiken because Gibson hoped to serve as governor.[18] Aiken was elected on November 5, 1940, and took his seat in January, 1941. He was re-elected in 1944, 1950, 1956, 1962, and 1968. During his time in the Senate, he served in a number of leadership roles including chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in Executive Departments in the 80th Congress and the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry in the 83rd Congress. He was a proponent of many spending programs such as Food Stamps and public works projects for rural America, such as rural electrification, flood control and crop insurance. He also had a great affection for the natural beauty of his home state, saying "some folks just naturally love the mountains, and like to live up among them where freedom of thought and action is logical and inherent."[19] His views were at odds with those of many Old Guard Republicans in the Senate. The role of labor unions, or more exactly the federal role in balancing the rights of labor and management, was a central issue in the 1940s. Aiken stood midway between the pro-union Democrats and the pro-management Republicans. He favored settling labor disputes by negotiation, not in Congress and courts. He voted against the stringent Case labor bill promoted by conservative Republicans. They in turn blocked Aiken's appointment to the Labor and Public Welfare Committee and persuaded conservative leader Robert A. Taft to chair it. Aiken spoke out in favor of unions but voted for Taft's Taft Hartley Act of 1947, and for overriding President Truman's veto. He argued that it was a lesser evil than the Case bill.[20] Aiken voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957,[21] 1964,[22] and 1968,[23] as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,[24] the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[25] and the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court,[26] while Aiken did not vote on the Civil Rights Act of 1960.[27] At first he supported civil rights but by the 1960s he took a more ambiguous position. He consistently favored civil rights legislation, from the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but usually with important qualifications and amendments. This ambiguity, which some called obstructionism, was criticized by militant civil rights groups and the NAACP.[28] Aiken took an ambivalent position on the Vietnam War (1965–1975), changing along with the Vermont mood. Neither a hawk nor a dove, he was sometimes called an "owl."[29] He reluctantly supported the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution of 1964 and was more enthusiastic in support of Nixon's program of letting South Vietnam do the fighting using American money.[30] Aiken is widely quoted as saying that the U.S. should declare victory and bring the troops home.[31] His actual statement was:

He added: "It may be a far-fetched proposal, but nothing else has worked."[32] His base in Vermont was solid; he spent only $17.09 on his last reelection bid. A north-south avenue on the west side of the public lawn at the Vermont State House has been named for him. He left office in 1975, succeeded by the first Democrat to represent Vermont in the Senate, Patrick Leahy. Leahy went on to become the Dean of the Senate, the title Aiken possessed when he left the chamber. Aiken and Leahy held the same Senate seat for more than 80 years combined, making them the back-to-back pair of Senators to hold the same seat for the longest. When Leahy retired at the end of the 117th Congress in January 2023, the two had held Vermont's Class 3 seat for a combined 81 years, 11 months, and 24 days.[33] Committee assignments

Retirement and deathAiken did not run for reelection in 1974.[40] He resided in Putney until mid-1984, when his health began to fail and he moved to a nursing home in Montpelier.[41] He died in Montpelier on November 19, 1984,[42] and was buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Putney.[43] Bernie Sanders, who had interviewed Aiken for the Vermont Life magazine in 1973, said of him in 2006: "I can’t say I have based my political work on his, but Aiken has always been a name and a person I’ve respected and admired. What I liked about him and what made him successful was his straightforwardness, his common sense, his down to earth-ness. He was clearly a man of the people.”[44] References

Further reading

Primary sources

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to George Aiken. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||